Sleuthing on the Trail of Stone, Part 3 of 3 Chronicling CPR Temples in the Bush

Come walk with me, and I will tell

What I have read in this scroll of stone;

I will spell out this writing on hill and meadow.

It is a chronicle wrought by praying workmen,

The forefathers of our nation—

Leagues upon leagues of sealed history awaiting an interpreter.

Although she could neither see nor hear, Helen Keller knew that stone can speak.

By touch alone she sensed the labour of unknown hands, reading in lichen-softened surfaces the chronicles of lives long passed. Here in British Columbia, our mountains hold the echoes of similar voices in old CPR stonework. Dense undergrowth shades weathered blocks; rain trickles along mortar lines set by men who believed their work would last as long as the peaks above. Forgotten walls and arches lie low in many places, patient beneath moss and the slow-falling needles of conifers, as though waiting for someone to harken to them.

...our western rainforests shelter [masonry] works no less compelling.

We’re accustomed to think of masonry as an ancient art in faraway places — in ruins smothered by vines, forgotten cities under monsoon skies. Yet our western rainforests shelter works no less compelling.

Along the path of the Canadian Pacific Railway, beyond the verge of the highway, granite piers rise among ferns; culverts arch like cloisters above clear glacier water; retaining walls press railbeds protectively against slopes.

One need not seek fabled cities abroad. Off the public path in the Selkirk Mountains or in the Fraser Canyon, our own forests hide our own antiquities.

I write as a stonemason, and as one who has walked among remnants with camera and notebook, and a reverence born of practice. My purpose is to pass along knowledge of a craft once prized by railways, and to recognise the men whose hands shaped and laid each block.

A stile built of local stone. The seated mason is the author, reflecting the tactile, interpretive connection Helen Keller describes in her verse.

This article concludes my three-part series on western stonework. Come, walk abandoned grades and along shadowed cañons — as the CPR once spelled them — feel the stones awaiting new eyes and ears patient to hear their stories.

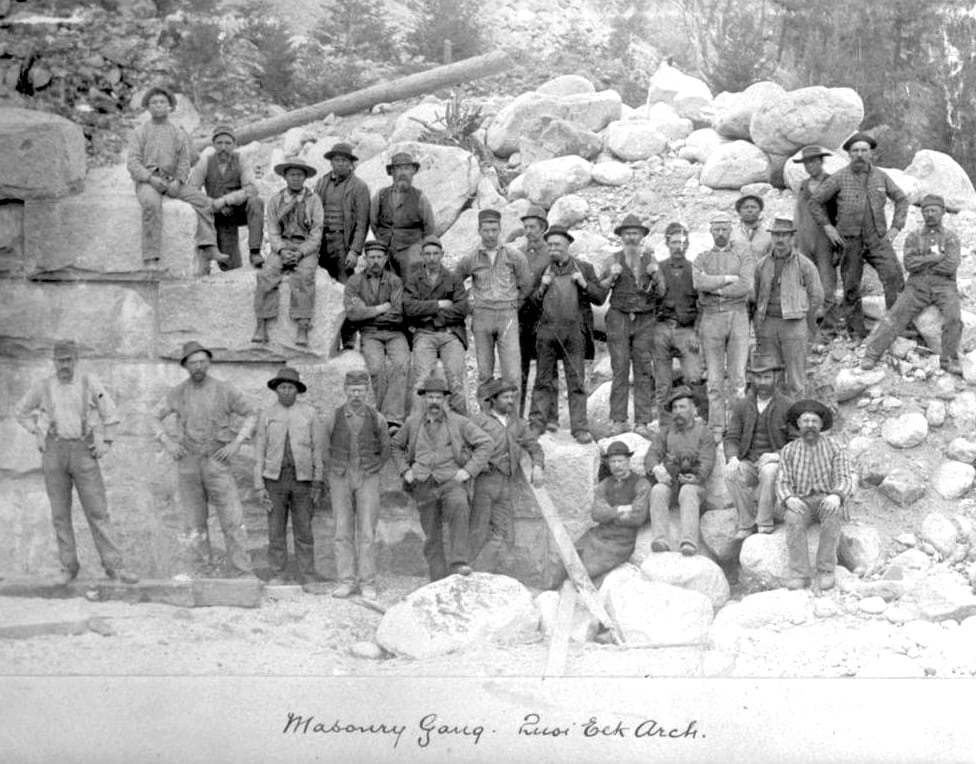

Part 1 and Part 2 examined two questions: whence the stone used by the CPR in western Canada, and who the builders were. Archival research and field investigation show that the principal source lay in the Fraser Canyon, at Camp Sixteen — also called Cathmar and Hells Gate — and that the workforce was far more diverse than popular lore allows. Italians of quarrying experience, Indigenous men of the river, and a smattering of settlers from elsewhere shared the labour. In this concluding piece I will introduce more of them, for their story remains under-told, even as their work endures.

...the workforce was far more diverse than popular lore allows.

Like Keller, we may trace meaning in stone. The masons’ craft was sidelined once concrete proved swift and economical, yet their work still resists the onslaught of Mother Nature. Rogers Pass is the finest place to sense it. There, in Glacier National Park, trails and interpretive signs lead over avalanche chutes and abandoned alignments — a landscape that once punished surveyors and navvies in equal measure until the line dove beneath the mountains in 1916.

Stone arch abandoned at Mile 99.5 of CPR Mountain Subdivision near Illecillewaet, BC. It stands at the eastern end of a 2.8-mile realignment between Downie and Illecillewaet to avoid active avalanche slopes. Span: 60 feet (18.3 metres). Photo © TW Parkin.

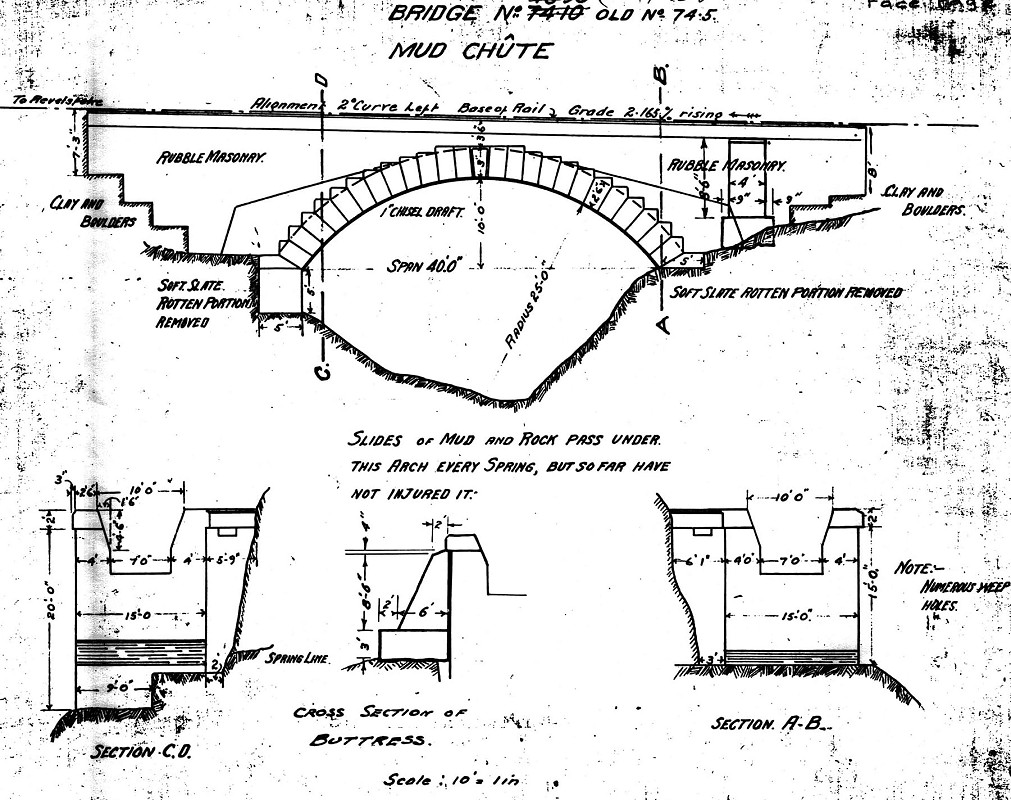

A CPR as-built diagram of a former stone arch in Glacier National Park, BC.

Rogers Pass is also welcoming. Most of the surviving masonry stands close by the Trans-Canada Highway, the park’s visitor centre provides context, and maps point the curious towards marked paths. Yet not every relic is signposted. Those willing to read early plans and tramp through bush may find additional piers, abutments, and stone-lined watercourses half-hidden among the hemlocks. Bears roam here too, as they always have, but adventure without an edge seldom stirs the soul.

The stones can still be admired, wherever they lie...

Beyond the park, other works described in these pages remain in service and fall within railway property. Exploration must respect boundaries; curiosity is no licence to trespass. The stones can still be admired, wherever they lie, and their stories are no less compelling for being partly veiled.

Note to the reader: To emphasize the men who have received so little credit for their efforts, I have highlighted their names within this text.

Culverts and Arches

On 21 April 1992 at Cherry Point on Kamloops Lake, BC, westbound SD40-2F no. 9003 rumbles over the granite arch at Mile 10.8 on Thompson Subdivision. In BC today, a dozen such masonry arches still support modern train weights, although most are remote from public access. Photo © DJ Meridew.

An arch is a self-supporting curved structure built to carry weight across an opening, whether dry ground or water. Where the span must also retain fill and conduct water, the form becomes a culvert — essentially a broader arch designed to carry a watercourse beneath a railway embankment.

As explained in Part 2, the CPR soon realised its high masonry standards could not be sustained with the funds available during initial construction. Timber offered a cheaper, quicker substitute. Contractors such as Andrew Onderdonk in the Fraser Canyon followed the same instruction. Timber structures lasted roughly a decade; once finances improved, the CPR began replacing vulnerable trestles and trusses with permanent masonry or steel, prioritising the weakest links first.

Glacier Creek Culvert

One such replacement stood at Glacier Creek near Glacier House on the western slope of Rogers Pass. The original 362-metre trestle, battered by high water and debris, also created a bottleneck as passenger trains paused at the hotel. In 1900 it was rebuilt as a double-track stone culvert, improving capacity and reducing maintenance.

Work proceeded in the typical sequence of the era: Thomas McMahon’s gang handling sand and mortar; Donald Bain’s men setting the stone; inspection by Edward Farr, active in the Pacific Division since at least 1881. All lifting was manual. Stiff-leg derricks hoisted blocks from flatcars, their poles anchored by the very stones soon to be set in place.

Similar stone culverts continue to carry streams beneath CPKC’s main line today.

The Glacier Creek culvert cost $12,501 and took about four months to build — with the creek flowing throughout. Once wing walls were complete, air-operated side-dump cars, designed by the CPR in 1892 filled the embankment and buried the old trestle[1].

As the fill settled (“shrinkage”), more ballast was added until the rotting timber no longer contributed support. Similar stone culverts continue to carry streams beneath CPKC’s main line today.

ACCIDENT ON THE RAILWAY.

Two Men Hurt.On Saturday morning, as the special with the Canadian Press Association was coming through the Kickinghorse [sic], the engine struck the guy rope of a derrick in use by McGregor’s bridge gang, who were engaged in repairing a bridge, at Glenogle. The result was that the derrick swung round, and [Alex] McGregor, the bridge foreman, and Edward Soucie, who were on it at the time, were thrown down. McGregor had an arm broken and his head badly cut, and Soucie had an arm and a rib broken. The men were brought on to the Golden Hospital, Dr. Sylvester, of Toronto, who was on the train … kindly attended to the inured men.

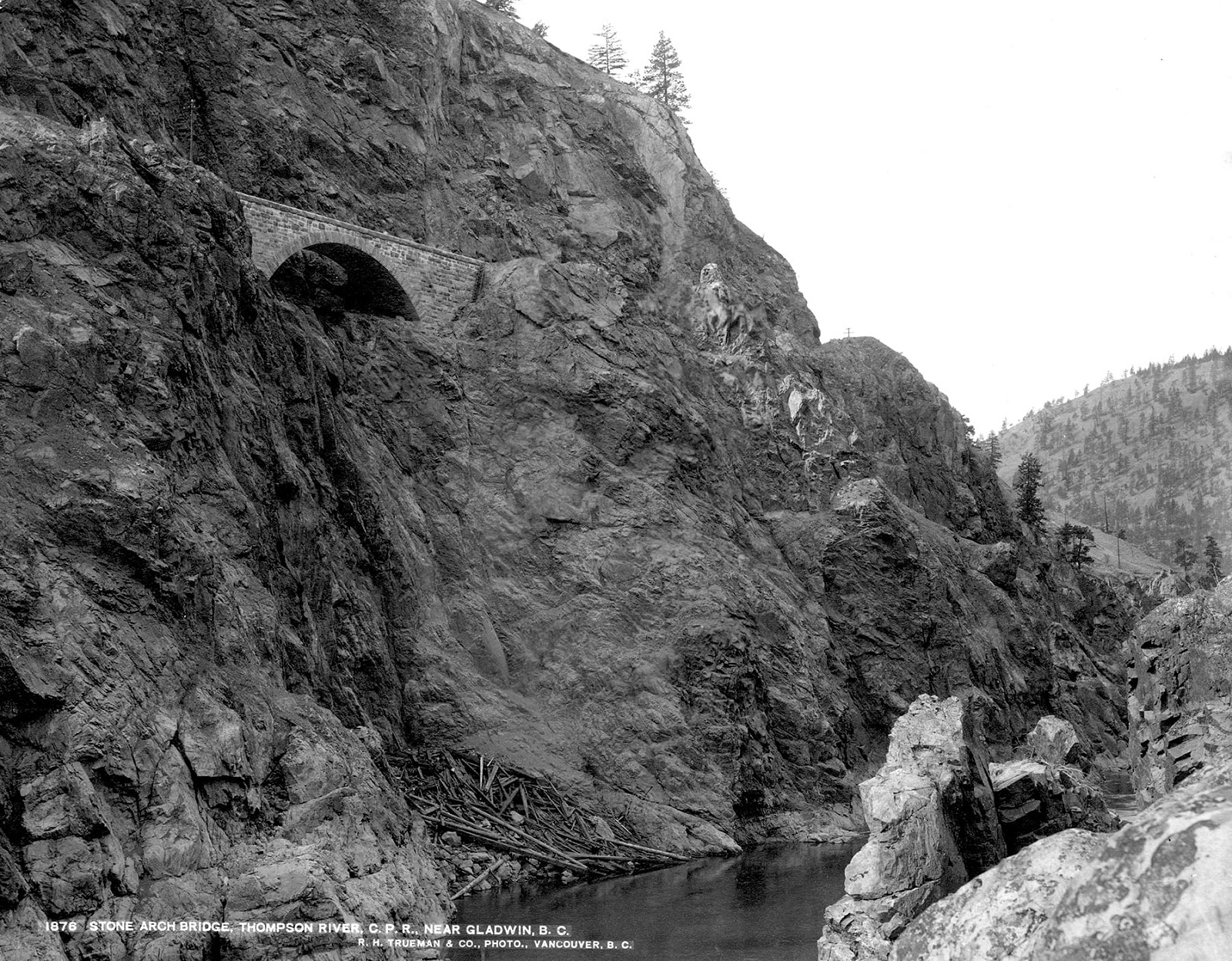

Jaws of Death Arch

“Jaws of Death” appears in Shakespeare’s Troilus and Cressida (1602) and later became attached to this perilous site above the Thompson River. The original 1884 timber truss was replaced in 1899 with this 24 m stone arch, built on steep rock faces prone to slides and falling debris. Today it is best viewed from rafting trips that pass beneath. Photo: R H Trueman, City of Vancouver Archives #2–39.

Other arches still bear modern train weights. One, completed in 1899, spans a steep gulch above the Thompson River. During construction in 1884, engineers first proposed a costly 300-metre tunnel to avoid unstable terrain. Budget pressure shortened it; that tunnel collapsed, killing Chinese labourers and giving the site its grim name.

A second engineer adopted a more drastic solution: driving a 60-metre tunnel beneath the failed one, packing it with 10,000 lbs of Judson powder, and blasting 80,000 tons of rock into the river — the celebrated “boss shot of the line.”[2] The resulting ledge required only a single 36-metre Howe deck truss, installed under hair-raising conditions.

Budget pressure shortened it; that tunnel collapsed, killing Chinese labourers and giving the site its grim name.

When that truss was later replaced by a stone arch, crews scaled loose rock from the cliff and eased the track inward to gain a few precious inches.

Using the original notches cut in the bedrock, they built a 24-metre stone arch, its weight held in suspension until the keystone locked it. Any slip would have meant a scream into the gorge and the Thompson’s gnashing maw below.

Westbound CP coal train travelling on CN tracks, with which company CP has reciprocal movement rights. This view is into the Thompson River. The masonry arch over the dry gully is at Thompson Subdivision Mile 87.7. Video © TW Parkin.

Bridge Piers

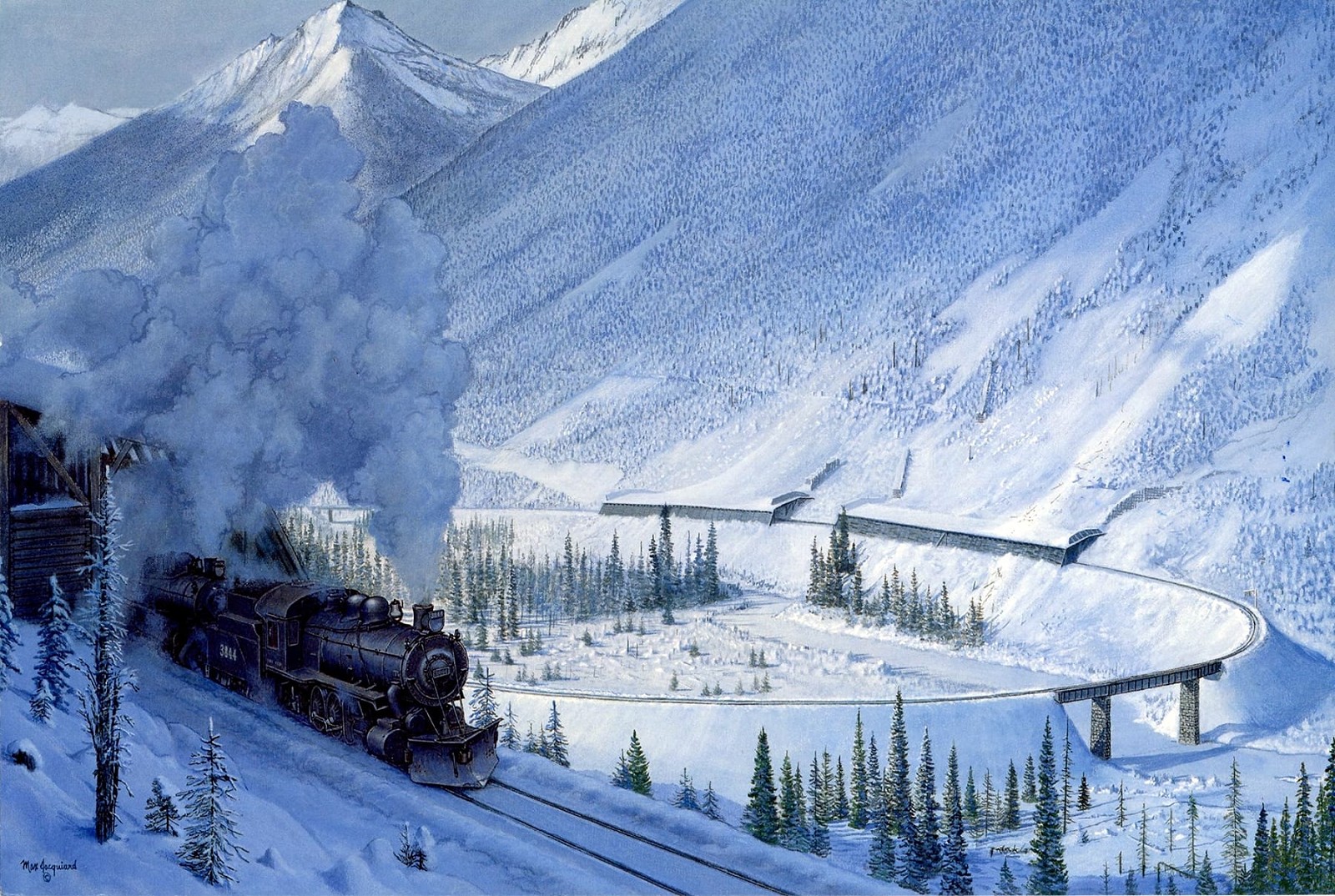

Loop Brook

(formerly Five Mile Creek)

Before the Connaught Tunnel opened in 1916, the CPR crossed the Selkirks on steep grades protected by extensive snowsheds. To ease the descent west of the summit, the line looped back upon itself. Here, eastbound locomotive no. 3844 moves through a sequence of snowsheds after completing the loops, in this painting by the late Max Jacquiard. All this trackage vanished once the tunnel opened.

Once the CPR forced a line across Rogers Pass, doubts soon followed. Engineer James Ross inherited Major AB Rogers’ survey — the same hand responsible for the “Big Hill” in the Rockies — and found it wanting in the Selkirks as well. Rogers had driven a straight tangent down the Illecillewaet valley from the survey office in Calgary; in the field, Ross met steep slopes, twelve avalanche paths, and intersecting gullies. Meanwhile Van Horne pressed for progress from head office in Montréal.

A peak of 1,962 metres now bears Ross’s name; Sykes’ name has faded unjustly.

Insight came not from Ross but a junior, Sammy Sykes, whose quick field work suggested a Swiss-style solution: ease the grade by looping the line back upon itself.

The resulting Loops added nearly four miles of track and required four major timber trestles totalling 763 metres, later supplemented by extensive snowsheds. A peak of 1,962 metres now bears Ross’s name; Sykes’ name has faded unjustly.

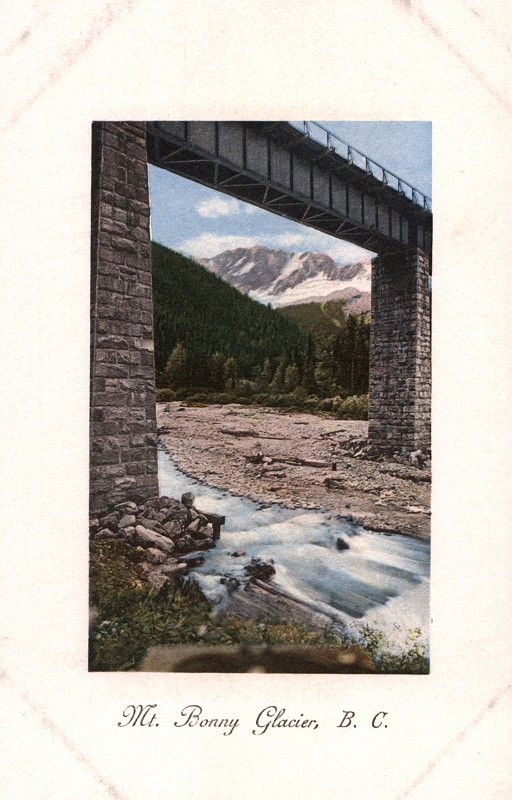

By 1896 the CPR had the cash to replace timber with permanence. Work continued until 1905–06. Granite piers rose at Loop Brook while concrete abutments were poured for the Illecillewaet crossing. Masons of both trades lived in bunk cars at Cambie siding (not today’s Cambie). Rivalry likely simmered: concrete was faster, and industry everywhere was turning toward it.

These stones replaced an earlier timber trestle. On this structure in 1906, a steel span being lowered into position fell, killing two men and injuring two others. The steelwork was removed in 1917, but many piers still stand in what is now a national park campground. Postcard by J Howard A Chapman, Victoria, BC.

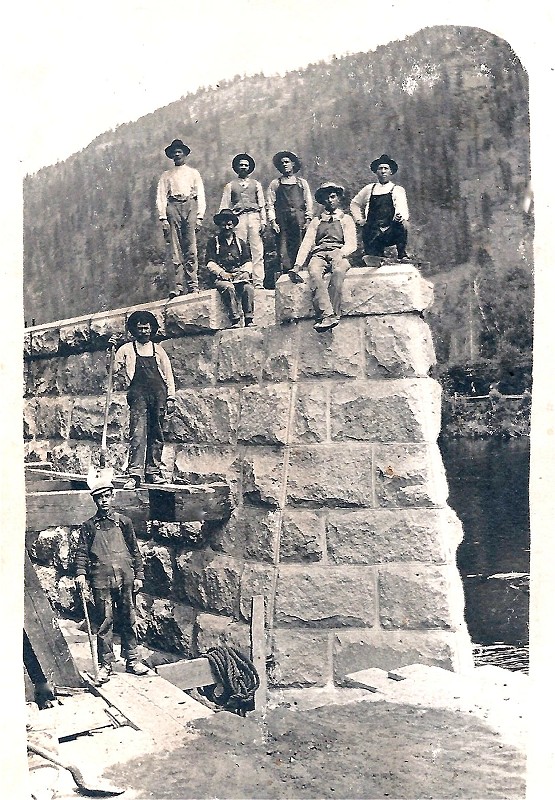

Postcard postmarked 26 January 1911 at Fife, BC. Written in Italian, this crew is building a bridge pier, location unknown. One of the men believed to be "Alfonso". Figure on extreme right may be foreman. Tools in hand include two trowels, a spirit level, a shovel, and a pick. The wet patch indicates where mortar was being made by the guy with the shovel.

Two ranks of stone piers still stride across Loop Brook and can be reached by trail. Forest now rises around them; the steel they once carried was salvaged in 1917, after the Connaught Tunnel rendered this alignment redundant. Glacier House lingered a little longer, its guests still touring nearby Nakimu Caves and climbing peaks, but by 1929 it too was gone.

Visitors today should pause at the short trail and interpretive signs. Running a hand along the granite courses gives some sense of the labour expended here, as Keller felt along New England’s stone walls. Seek out the fallen pier scarred with chiselled “H” marks — an intriguing relic from the masons themselves, toppled by an avalanche in the 1970s.

SHOCKING ACCIDENT

Collapse of Another C.P.R. Bridge—Two Men Killed and Two InjuredThe city was shocked on Friday afternoon by the news of another bridge disaster on the C.P.R. main line, this time at the Loop where the B.C. Contract Company have a contract to build a steel bridge for the C.P.R. This bridge is elevated 100 feet above the bed of the stream. A span 70 feet long was being lowered into position about 11:30 a.m., when the tackle gave way and the span was precipitated some feet below. In its crash it killed two men, named [Camille Muylaert] and [James J Ritch], who were members of JC Fraser’s bridge gang. It appears the contractors were short of men and got Mr. Fraser’s gang to help . . . Mr. Leach, engineer for the contractors, had a narrow escape, as he was standing right alongside the girder when it fell.

Retaining Walls

Fraser Canyon

About 15 miles north of Yale, these cliffs were once notorious enough to earn the name “the Slaughter Pen.” Primary contractor Andrew Onderdonk organised this 4 July 1883 excursion for guests to view current works. The uneven-legged timber supports, later replaced by stone walls, became known as “grasshopper trestles.”

BC Archives photo A-09251.

The earliest CPR retaining walls in the west appeared in the Fraser Canyon under contractor Andrew Onderdonk in 1880. The terrain demanded support wherever the line clung to steep slopes. Chief Engineer HJ Cambie’s early inspections noted problems: walls set on soft ground, use of rounded river cobbles, and other structural shortcomings. These were likely the result of untrained labour and lack of suitable stone at the outset; quality improved as experienced masons arrived.

Reliable building stone became available once construction reached Hells Gate. A camp established there, later known as Camp Sixteen, occupied level ground beside fresh water and, crucially, beneath a cliff of well-fractured granite.

It soon developed into the CPR’s principal western quarry, supplying works in the canyon and as far afield as Loop Brook — a distribution confirmed by petrographic analysis (see Part 2).

With demand gone, the quarry was abandoned.

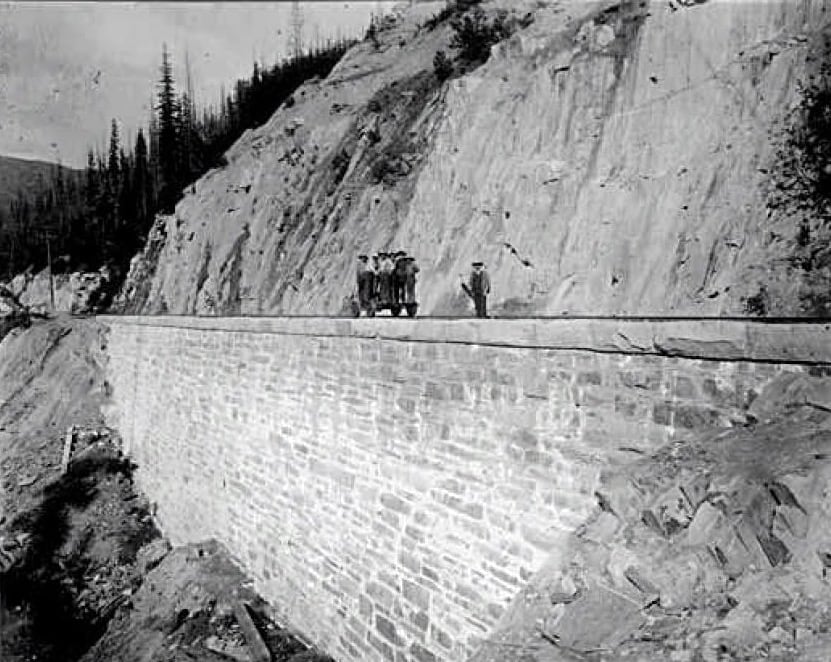

After the 1881 directive limiting stonework to essential structures, fill and timber “grasshopper trestles” — supported on uneven legs — carried the railway across side slopes. When finances improved in the 1890s, these makeshifts were steadily replaced with masonry. Stone remained the preferred material until about 1912, when the final shipments left Camp Sixteen and concrete construction took precedence.

With demand gone, the quarry was abandoned. Like many industrial sites that drove British Columbia’s early development, it slipped back to silence and scrub — the once-active benches and spoil piles gradually overgrown, their purpose legible only to those who know where to look.

This scene of railway construction past the “Alexandra bluffs” was taken about a year after the fall of Engineer Eberts. His gravestone may be seen here, in Victoria.

Mr. Melchior Eberts had charge as Engineer, the work for some miles on either side of the suspension bridge embracing the “big tunnel” and in early 1881, he had one morning laid out the tunnel and was hurrying back to his office, which was in the toll house at the bridge, and in passing over the bluff immediately north of it, fell and slid head first about 60 or 80 feet on the grade and over it until his clothes were caught on a stump, otherwise he would have gone in the Fraser River…Dr. Hanington and the writer were notified by telephone to get there as fast as horses could go but his skull was fractured in many places and he never regained consciousness but died next morning.

Beaver Canyon

Heckman’s note for this 20 July 1899 photograph reads: “Stone wall at Beaver Canyon built below tracks at CPR M 444.4 — T[restle] at Hells Gate.” In faint pencilling he added: “Enrico Ender, Lytton, BC.” Ender — an Italian-born foreman — is one of several masons newly identifiable through research. Photo: JW Heckman, Vancouver Public Library #856.

A 28-man masonry crew constructing a railway culvert in 1895. Their names are unrecorded, though at least four Indigenous workers are present. Context for their project appears in my companion story. BC Archives photo D-01482.

Another narrow defile on the east slope of the Selkirks once tried to borrow the name Hells Gate. When its admirers finally stood before the real constriction on the Fraser, the borrowed title quietly died — wisely. Here, too, early timber supports later needed replacement.

Joseph Heckman photographed several such works and, in a rare departure from his usual practice, recorded one labourer by name: “Enrico Ender, Lytton, BC.”

That note caught my attention.

Many writers have assumed BC’s railway stonemasons were largely British. So I followed the clue.[3] Genealogical and census records show Ender — also rendered Andrew Ender — was born in Italy and settled at Cisco/Lytton, marrying a Thompson River woman around 1886. He appears in directories by 1894 as a foreman, and remained in that role until his death in 1909 at age fifty. He spent his working seasons along the Fraser and Thompson, raising retaining walls and other masonry the hard way — with skill, repetition, and no expectation of recognition.

His headstone still stands in Lytton Cemetery. One mason remembered; thousands not. But his work holds, and that is the truest monument.

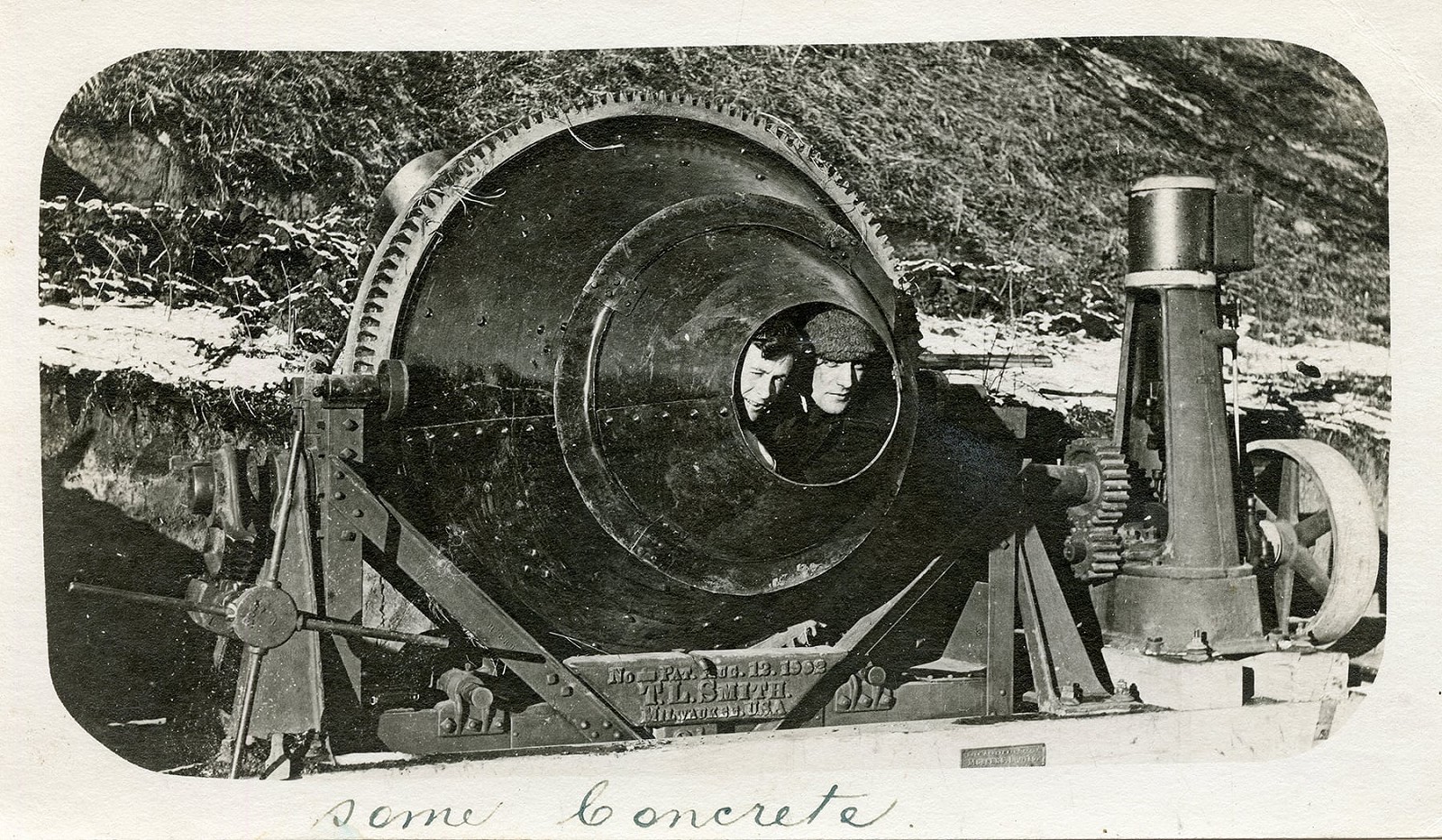

Introduction of concrete in BC

A 1912 postcard showing a concrete mixer crew at work — and at play. By this time, concrete had largely displaced stone on western railways, and mechanisation was reducing manual labour. The mixer here serves the Canadian Northern Railway bridge at McLeod River, near Whitecourt, AB. CNoR later became CNR. Photographer unknown.

The CPR left no record of the precise moment concrete superseded stone. There was little reason to note it; few could have foreseen how rapidly the material would dominate. Architectural historians Barrett and Liscombe mark 1889 as the first major concrete use in BC — Victoria’s courthouse.[4] Within the railway, the earliest photographic evidence I have located is a Heckman image of a concrete culvert at Field, dated 11 July 1899.[5]

Nearby, at Palliser in the Kicking Horse Canyon, unstable ground produced the infamous “mud tunnel.” The first bore, driven in 1884, soon proved untenable and was bypassed in 1887 by a sharp diversion. By 1905 the curve had become a bottleneck and a new tunnel was driven, this time lined in concrete to resist swelling ground. It opened 31 July 1906.

...the [concrete] material struggled against the geology.

This lining was reinforced with metal — an innovation just reaching engineering literature, as the first English-language textbook on reinforced concrete appeared the following year. I suspect the CPR may have used redundant light rail for reinforcement; the company did so in the 1906 divisional roundhouse extension at Revelstoke.[6]

Even so, the material struggled against the geology. In 1953 the overburden was stripped away, leaving a curved concrete shell to guard against snow and sloughing. It stood for decades, then disappeared in 1982 — progress erasing its own early experiments.

A small piece of an international shift, briefly visible, then gone.

The mud tunnel being constructed by the C.P.R. to cut off the sharp curve west of Palliser is giving employment to 120 men. The work is proving very troublesome as it is in swelling ground, which crushes the timbers. The tunnel is being lined with concrete, three to four feet thick, reinforced with iron, but owing to the nature of the ground progress is very slow and the work cannot be completed under six months. The company have a steam rock crusher on the ground to supply the stone for the concrete. Although only about 12 chains [241 m] long it will be a costly piece of work.

Demise of Stonemasonry

What became of the men whose skill in shaping stone was rendered obsolete when concrete arrived? The CPR left no formal record of their fate. Evidence suggests that Camp Sixteen shipped its last stone around 1912, roughly a decade after concrete began appearing on western railway works.

In effect, the company made its stonemasons redundant within a single working generation.

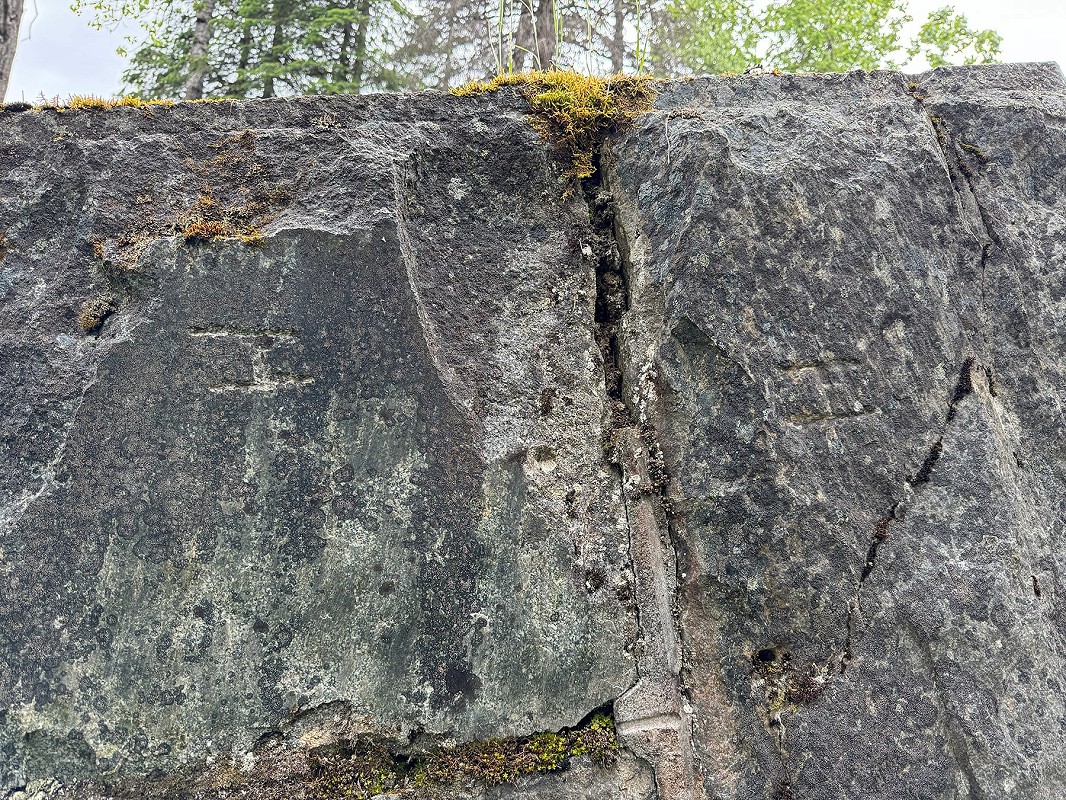

Masons occasionally marked their work with initials or symbols, though usually in hidden places. The purpose and era of these letters remain uncertain; they appear on a toppled pier, hence read sideways. Photo © TW Parkin.

Blocks of granite left behind at the loading spur at abandoned CPR quarry at Cathmar, BC. Note the mainline tracks in the background. Find more about the quarry in Part 2. Photo © TW Parkin.

One man’s story illustrates the transition. Giuseppe “Joe” Peressini, an Italian-born mason, reached Revelstoke in March 1903 with six compatriots from the Alps. According to local historian Ruby Nobbs (Revelstoke: History and Heritage), he worked on the Loop Brook piers, a major retaining wall on the Fraser, and later built the original Last Spike cairn at Craigellachie in 1927.

Peressini adapted. By 1921 he was foreman of the CPR’s Bridge & Building gang at the Palliser tunnel, now working in concrete. After a day’s shift that October, the tunnel roof collapsed; an eastbound freight plunged into the obstruction and six railwaymen died. At the inquest, Peressini’s crew was exonerated — the failure was geological, not human — but the document confirms his continued employment, responsibility, and transition to the new material.

These men did not cling to an older craft; they recognised change and moved with it

Two of his fellow immigrants went on to become prominent builders in Revelstoke, introducing cinder block construction as early as 1906. These men did not cling to an older craft; they recognised change and moved with it. Peressini’s early work near Rogers Pass, when stone and concrete stood side by side, must have shown him clearly which material would prevail.

The stonemasons were not discarded because they lacked ability; they were overtaken by an industrial shift that rewarded speed and volume over craft. A few, like Peressini, carried their knowledge forward. Many did not.

Conclusion

Railway history often celebrates its generals — Van Horne, Rogers, Ross — and its architectural showpieces. They deserve notice. Yet the permanent way rested on the labour of men seldom named: quarrymen, stonecutters, and masons who lifted, trimmed, and set the material that held the early CPR to the mountainsides.

I speak for them because I understand their trade. The sub-grade structures they left — culverts, piers, abutments — show competence, judgement, and pride. They are not ornamental, yet they possess dignity. Modern engineering schools no longer teach the principles behind this work, and so stone is mistrusted today. Meanwhile the old arches still carry trains, as reliably as many of their counterparts in Europe.

The sub-grade structures they left... are not ornamental, yet they possess dignity.

Another myth deserves dispelling. BC’s masonry is often credited to Scots by default. My research finds no evidence of systematic recruitment from Britain, and considerable evidence of Italian craftsmen applying skills under-valued in their own country.

They did not travel as “Old Country experts”; they simply arrived at a place that needed them, and proved equal to the task. Indigenous men and local settlers stood beside them. Together they became Canadians — and they left structures that have outlasted those who doubted them.

If you wish to see their legacy, go out and look: at Loop Brook, at Hells Gate, at the abandoned alignments of Rogers Pass, in Kicking Horse Pass.

The stone remains. So does the quiet testimony of the hands that set it.

References

- CPHA document archive, folio MoW G-774, ‘Automatic Air Dump Car’.

- From the Inland Sentinel, 7 December 1882, Yale, BC.

- Original held CRHA archives/Exporail, Canadian Pacific Company fonds, Saint-Constant, QC.

- Francis Rattenbury and British Columbia: Architecture and Challenge in the Imperial Age ©1983 Anthony A. Barrett and Rhodri W. Liscombe, UBC Press, Vancouver, BC.

- Vancouver Public Library historical photo collection, #887. Also held by CRHA archives.

- Meridew, David J., personal correspondence regarding 1979 roundhouse demolition, 14 May 1998. Nearby, the reuse of 80# rail as rebar was similarly designated in the 1914 under-crossing of the Illecillewaet River at Glacier, BC (culvert design no. 8566, CPHA document archive).

Did You Enjoy This Article?

Sign Up for More!

“The Parkin Lot” is an email newsletter that I publish occasionally for like-minded readers, fellow photographers and writers, amateur historians, publishers, and railfans. If you enjoyed this article, you’ll enjoy The Parkin Lot.

I’d love to have you on board – click below to sign up!