Sleuthing on the Trail of Stone, Part 1 of 3 Destination Disaster – James Hector and the CPR

[Dr Hector] was admired and talked about by every man that travelled with him, and his fame as a traveller was a wonder and a byword among many a teepee that never saw the man.

Imagine yourself as an internationally respected scientist, knighted by Queen Victoria for service to the British Empire, and travelling to Canada as an honoured guest of Canadian Pacific Steamships and Railway (CPR).

How might it have felt to be fêted en route, greeted by officials, photographed and quoted, all for an accident that wasn’t unusual for your era? What might you do, primed to relive with your accompanying son, the adventures of your youth, when you were his age?

On 7 August 1903, Sir James Hector, recently retired from academic and geological positions in New Zealand, landed in Vancouver, BC, with his 26-year old son Douglas, intending to show the young man the Rocky Mountains and to point out places of his exploits as a young explorer in those shining ranges.

The CPR had arranged everything for a public relations extravaganza. But within days it all became death and dissolution.

He also hoped to visit Peter Erasmus, an old Métis friend whom he hadn’t seen in over four decades. The CPR had arranged everything for a public relations extravaganza. But within days it all became death and dissolution. The beloved son died, the celebrations were cancelled, and Sir Hector never saw Erasmus at all. He immediately returned home, soon to die himself in sharply declining health.

Apart from a few place names in the Rockies and two stone monuments, his sad tale has been largely forgotten. Through this account, may he be re-established in his due place.

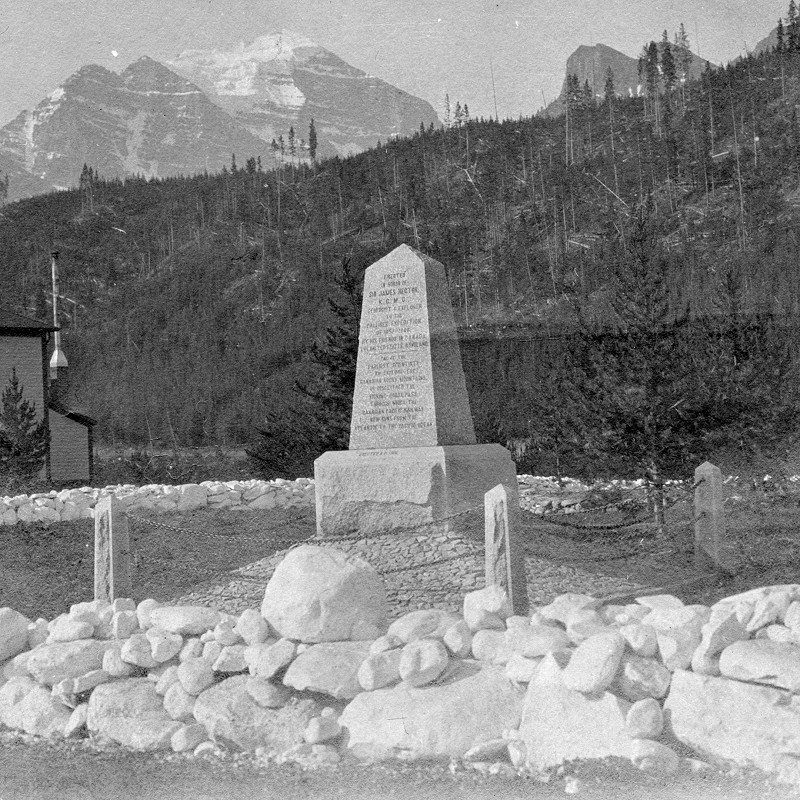

Landmarks remaining include the former Hector railway siding on the CPR and Mount Hector with its nearby lake in Alberta. Lost to common knowledge are two granite monuments; a small obelisk sited in an encroaching forest on the Great Divide, and a coffin-shaped stone lying in Mountain View Cemetery at Revelstoke, BC. All, including the stones’ source quarry, are inextricably linked by the Fraser Canyon, the CPR, and this author’s masonry research.

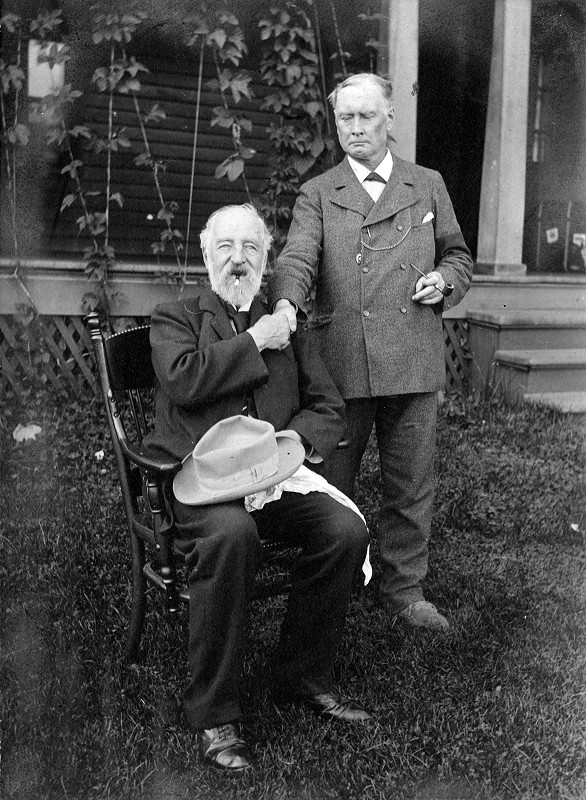

Sir James Hector (seated) with Edward Whymper at the CPR hotel in Revelstoke, BC, following the funeral of Hector's son on 17 August 1903. They had met the day prior at Glacier House. Photo courtesy of City of Vancouver Archives CVA 371-513.05. Image by Mary Schaffer.

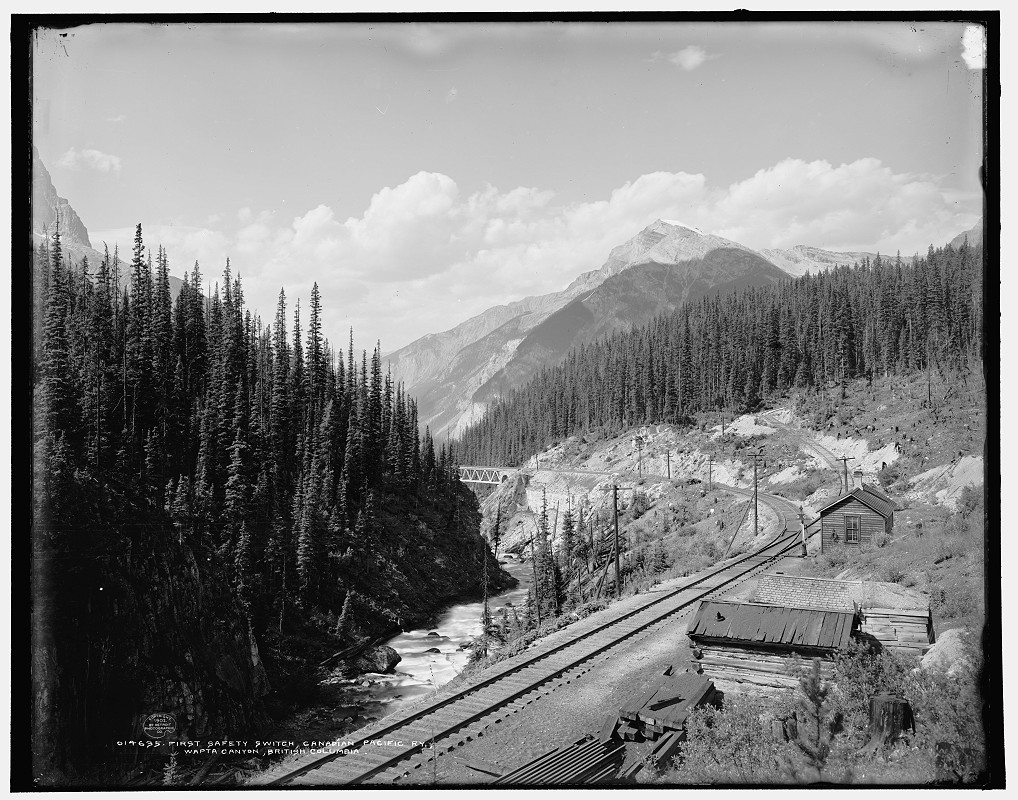

This 1900 photo shows the safety switch on the ‘Big Hill,’ Kicking Horse Pass, BC. James Hector and Peter Erasmus had traversed this dense bush upriver in 1858—decades before the CPR built down this same slope. The switch is set for the runaway spur, as was procedure. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC.

Heroes of Empire

Sir Hector’s visit had been initiated by letter from CPR President Thomas Shaughnessy (later addressed as Sir himself) to Sir James in the spring of 1903, proposing that Hector retrace some of the route of his early exploring party and meet another foreign guest, with the expectation that they would find appreciative audiences and significant media attention regarding their accomplishments. Unknown to Shaughnessy was that, at home, his foremost guest was overdue for retirement and being criticized for such, despite an illustrious career1.

The other invitee was Englishman Edward Whymper, a similarly aging, though still-famous mountaineer and scientist in his own right. He came to fame in 1865 with the first successful ascent of the Matterhorn in the European Alps, though his grand effort was immediately overshadowed by the falling deaths of four companions on the dangerous descent.

The simultaneous triumph and tragedy of his accomplishment catapulted Whymper into international fame for the rest of his life.

The simultaneous triumph and tragedy of his accomplishment catapulted Whymper into international fame for the rest of his life. He subsequently made a living through writing, artistic illustration, and public speaking about his various expeditions.

He continued to pursue foreign climbing and conducted experiments on altitude sickness. Whymper’s career never escaped the shadow of this tragic climb.

Whymper was already in British Columbia when the Hectors arrived. His assignment with the Canadian Pacific was more comprehensive than that of his senior acquaintance. For the previous two years, Whymper had been under contract as a consultant to the railway, which hoped that his writing and speaking would boost tourism at their four luxury hotels in the western mountains, all situated in spectacularly scenic areas.

Mountaineering was more popular in those days than it is now, both in Europe and North America, and Canadian summits were de rigueur among the international elite. Even 18 years after the railway’s completion, first ascents still awaited wealthy and refined ‘explorers’ during the time of this story, in 1903.

29 August 1858: Intrepid Explorer

Wapta Falls spans the width of the Kicking Horse River, dropping 30 m (100') in Yoho National Park, 24 km west of Field, BC. An easy 2.4 km trail leads from a short drive off the Trans-Canada Highway. Video © TW Parkin.

Decades before, James Hector was engaged by the 1857-60 British North America Exploring Expedition (more easily named for its leader Captain John Palliser, as the Palliser Expedition), commissioned in Britain to explore, map, and scientifically document lands west of Lake Superior and to the north of the still-informal 49th parallel border, and east of the Columbia River.

As The Canadian Encyclopedia explains, “The explorers amassed astronomical, meteorological, geological and magnetic data, and described the country, its fauna and flora, its inhabitants and its ‘capabilities’ for settlement and transportation.”

A railway through it hadn’t yet even been conceived, but one of six passes those explorers traversed through the Rockies was eventually chosen by the CPR in 1883. It marks the Great Divide of waters flowing east to Hudson Bay and those flowing to the Pacific.

Dr Hector, the team’s young geologist and surgeon, was kicked senseless by a horse...

Alongside that river’s watershed, Dr Hector, the team’s young geologist and surgeon, was kicked senseless by a horse which was damned tired and fed up after weeks of hauling somebody else’s breakfast over horrific routes while required to forgo its own Wheaties. Hector lived to tell the tale, and probably earned more than a few beers to encourage his tale.

His party was in the process of swimming its pack train across a glacier-fed river above Wapta Falls, a frightful white drop of 60 feet. Hector wrote:

. . . a little way above this fall, one of our pack horses, to escape the fallen timber, plunged into the stream, luckily where it formed an eddy, but the banks were so steep that we had great difficulty in getting him out.

In attempting to recatch my own horse, which had strayed off while we were engaged with the one in the water, he kicked me in the chest, but I had luckily got close to him before he struck out, so that I did not get the full force of the blow. However, it knocked me down and rendered me senseless for some time.2

No one kept a timepiece on the patient, and the confused records today show Hector was unconscious anywhere from two to six hours. Evidently he gave no sign of movement, breath, or heartbeat, but also likely was that his companions didn’t know how to properly assess their inert leader (Hector’s group was on a side-assignment for their captain, Palliser).

We all leapt from our horses and rushed up to him, recalled Peter Erasmus, but all our attempts to help him recover his senses were of no avail. We then carried him to the shade of some big evergreens while we pitched camp. We were now in serious trouble, and unless Nimrod [their hunter] fetched in some game our situation looked hopeless. One man stayed and watched the unconscious doctor.3

When Hector revived, he must have been disconcerted by the shallow grave open nearby because erroneous live burial was a peculiarly Victorian horror. Meanwhile, Hector’s dedicated men had been yanked emotionally from the chaos of scattering horses, to sudden death by an excited beast, then to the miracle of resurrection.

Decades later this site carries the name Kicking Horse River.

The good doctor was too pained to open his own medicine chest, so gave instructions to prepare a reliever on his behalf. Still rattled by events, Erasmus wouldn’t do so until Hector signed a waiver declaring that his friend was acting under his specific direction and was not responsible for any mortiferous reaction!

Decades later this site carries the name Kicking Horse River. Days later, their starving, bedraggled party was barely able to hobble its way over the pass which was headwaters of the Kicking Horse, also called the Great Divide. This route too, became the later salvation of the CPR and a topic of this article.

13 August 1903: 45 Years Later

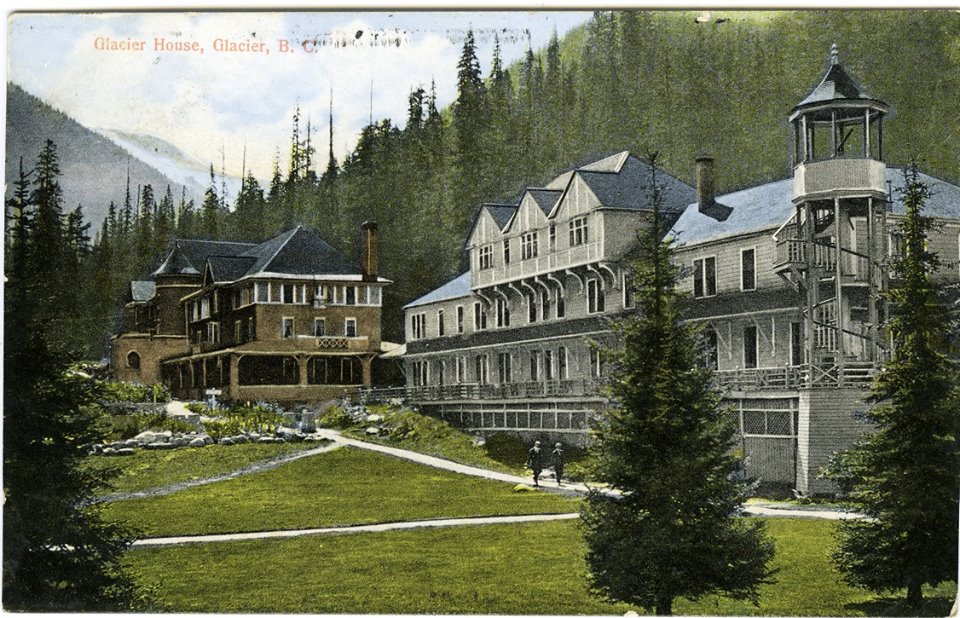

The CPR hotel in the Rogers Pass as it looked at the time of this story. From a hand-coloured postcard.

There is one place I mean to see, and that’s my grave! Yes, I’m sure I can go to the exact spot, Hector said, bringing his hand down emphatically on a knee.4

A small audience surrounded the grand old man in the cosy lobby of Glacier House, the CPR hotel near the summit of Rogers Pass in the Selkirk Range. He had arrived that afternoon on the Pacific Express with son Douglas, and was warmly welcomed by Mrs Julia Young, the manageress much beloved by guests and employees alike.

Another guest present was Mrs Mary Schäffer, artist, author, and mountain woman. Although from Philadelphia, she knew the Kicking Horse legend and paid the venerable gentleman close attention. In time, she developed into an historian and explorer in her own right.

Sir Hector [...] virtually ignored the growing complaints of Douglas...

Sir Hector was in his glory. So much so that he virtually ignored the growing complaints of Douglas, who had been suffering pain since disembarking in Vancouver. Dr. Hector had trained as a surgeon, but that was briefly in his youth, and he had since been employed in geologic and administrative matters most of his career. So he wisely asked another doctor present, Charles Schäffer, husband of Mary, for his opinion. But Dr Schäffer was an ophthalmologist!

Nevertheless, he diagnosed appendicitis and recommended immediate removal to Revelstoke, the nearest medical facility—44 miles distant by rail. Hector dithered, but abruptly in the night caught a westbound freight, gaining passage in the caboose for himself and his heir.

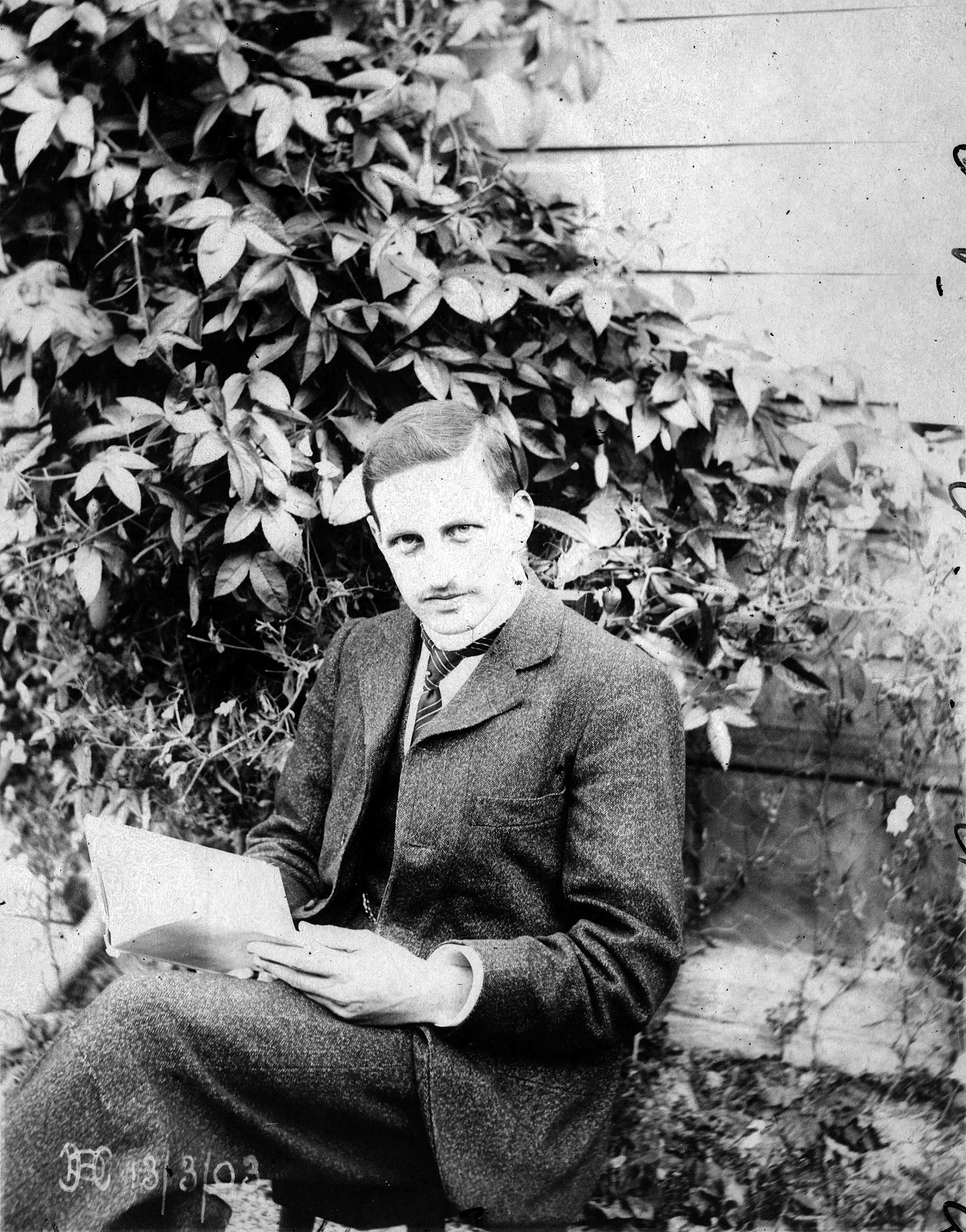

Douglas Hector photographed at home on 18 March 1903, before embarking on his fateful journey. The Hector family was known for intellectual achievement across generations. City of Vancouver Archives CVA-371-513.09.

Douglas’s swollen appendix ruptured before his operation. The procedure provided temporary relief from pressure, but infecting bacteria escaped into his abdominal cavity and multiplied.

He died the next day.

This was prior to the discovery and use of antibiotics. Hector the senior was now taken under the kindly wings of CPR superintendent Thomas Kilpatrick and his new wife Elsie, recently matron of Revelstoke’s Queen Victoria Cottage Hospital where Douglas had been admitted.

Sir Hector telegraphed those he knew at Glacier House: 24 hours too late. We could not save him.

Mary Schäffer was stunned as she read the terse statement.

Little did we think, she wrote, when the snowy-haired traveller descended from the train at Glacier, that hopes were to go unrealized, and that he would return in sorrow to his home, leaving a young, bright son, to rest forever in the valley of the Columbia.5

After the Hectors had left Glacier, Edward Whymper arrived on the Atlantic Express. He had been tracking the progress of the famed man through newspaper accounts, and was scheduled to meet him later. But as he was in nearby Donald at the time, suffering rainy weather, lack of beer, and a badly infected foot, he decided to meet Hector early. Dr Schäffer, also a stranger, was again called to examine a body part outside his specialty (eye conditions).

He had infected and swollen feet from walking the track all the way from Field...

His advice: keep off your feet, which was the obvious thing to say because Whymper’s boots no longer fit. He had infected and swollen feet from walking the track all the way from Field in a strange self-orientation to mountain scenery along the line.

His ‘research’ didn’t generate any ideas useful to the CPR, but they kept him on for another season, probably hoping he would produce a magazine article or two promoting tourism to the area. Nope—as implied earlier, Whymper was notorious for his dismissal of people he deemed of inferior status. He never produced anything worth the investment that the company made in him. This must have irked Thomas Shaughnessy, known as a notorious penny-pincher. In his daily journal, Whymper wrote:

He [Dr Schäffer] let out casually that he was going to Revelstoke tomorrow, to attend the funeral of Sir James Hector’s son, and I arranged to go too.

17 August 1903: Broken Spirit

The funeral cortege of Douglas Hector at the home of CPR superintendent Thomas Kilpatrick and his wife, Elsie. The Kilpatricks stand either side of a pole; to Elsie’s left is civil engineer Mr F Allwood. Further left, Dr Schaffer and wife Mary flank Sir James, hat in hand. To Mr Kilpatrick’s right are J Mathison (possibly a bridesmaid for the Kilpatricks), Whymper (seemingly ready to flop backward—he was a prodigious drinker), and Mrs Gleason, possibly hiding her facial injuries. City of Vancouver Archives CVA 371-513.07. Photo editing by JS Thorne.

Five mourners from Glacier House now crammed into yet another caboose, but their train was delayed and painfully slow. Near Illecillewaet, a sudden stop threw one of the ladies, a Mrs Gleason, forward through the cupola window, and more blood was shed. Screaming, she was lifted down and dabbed with handkerchiefs. Whymper was unsympathetic, writing:

. . . it was then seen that she had got one cut on her nose and another on the upper lip. She was capable of reparation, but the window was not.6

Finally they walked to the Kilpatrick home where the body was lying and joined the funeral cortege. Whymper mentions being introduced to a Mr McArthur (looked much younger than I should have supposed), a government surveyor engaged in a big project at that time, defining the tangent of the 49th parallel. His attendance was probably simple coincidence, but he may have been invited as one who could tell Hector about his current project, still incomplete since the latter’s 1858 visit!

Sir Hector and Whymper were previously known to one another by reputation and correspondence only. Whymper wrote in his daily journal:

In returning from the cemetery, Hector wished me to sit opposite him, and we talked all the way back. It would have been unfeeling of me to have asked the questions I wished to put to him, and I let conversation drift as it might. It came out from him that he had retired from the service, and had got a large family. He talked of coming to England, and asked me to remember him to all his friends over there. I endeavoured, unavailingly, to get him to come back with me to Hector’s Pass; but he had made up his mind to return home, and he left this afternoon upon No. 1, for Vancouver. Before he left, he was photoed. right and left by the Gleasons. I should have left him alone—but he did not seem to mind it.

CPR officials tried to turn Sir James’s course as well, but he was impenitent. His spirit was crushed and he knew he was now unable to perform for the benefit of the company, no matter how much they appeared to make it all about him. After a final series of somber photographs at the CPR hotel above the Revelstoke station, the mournful group bid farewell.

June 1906: Carved in Stone

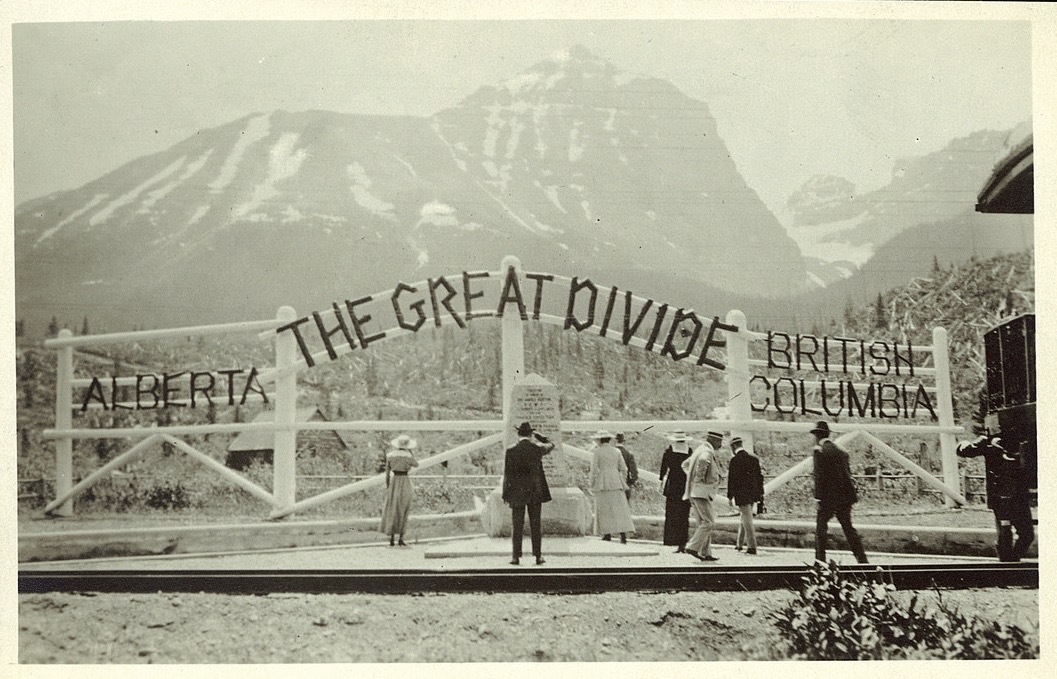

One might imagine the CPR had some plaque, some aesthetic erection, ready to unveil when Hector would have reached Kicking Horse Pass. A few years after, they were stopping summer passenger trains at the Great Divide to view this natural wonder.

Was the original publicity to have been no more than a handshake across a forking stream, or a few photographs? Unfortunately no record remains of what was intended, or taken away. Shaughnessy’s shiny idea had tarnished, and thought too sad an irony to carry forward, perhaps. Best buried under a rock.

Admirers of Sir Hector didn’t let that happen. Even before 1903 was out, the Schäffers began advocating for a memorial of some kind, and allied with powerful personality Arthur O Wheeler, a Canadian government surveyor and future founder of the Alpine Club of Canada. Their desire included a gravestone for Douglas as well. It took three more years, and a measly $50 cheque from Shaughnessy, before sufficient funds were raised. A stonemason was hired to carve and install both blocks. Superintendent Kilpatrick provided the stone. It wasn’t his own, but he knew a suitable quarry and arranged for its transportation.

Douglas Hector’s mossy headstone in Revelstoke’s Mountain View Cemetery is carved to resemble a casket. Its heavy weight has required several liftings for under-filling over time. Brushing the end reveals the inscription: ‘Douglas Hector of Wellington, NZ. Died 15 [sic] August 1903, aged 26 years.’ Photo © TW Parkin

Sir James Hector’s memorial as initially placed beside Laggan station, AB. Later, it was moved west to the Great Divide, but even there, was repositioned from time to time.. Photograph circa 1906. City of Vancouver Archives CVA 371-513.10.

The source of these stones has always been a question. Parks Canada has no records, despite long providing interpretation for this site (lying between Yoho and Banff National Parks). The scholarly journal Alberta History thoroughly examined these details in 2002, but couldn’t determine any source other than “in the Cascade Range.” Wheeler indicated it came from a former Rocky Mountains Park.7 Neither is correct.

I, the author, am both a scientist and a stonemason. My research for this article led to an overgrown quarry alongside a former CPR siding in the Fraser Canyon. It’s located in BC’s Coast Range, and is within the CP subdivision called Cascade. The locale was an industrial stone source first mined during the days of construction by contractor Andrew Onderdonk, and some of that stone is still in active use on the mainline today.

In two articles subsequent to this, I will discuss how crystalline analysis confirmed this quarry, how engineering of the Victorian era is still relevant today, and how this source of commemorative stone was put to use in other structures for the Canadian Pacific Railway.

This monument lies directly on the border between British Columbia and Alberta. It is named the Great Divide because it separates the watersheds of the Pacific from the Atlantic Ocean, being the height of the continent. Photo © TW Parkin.

The crystals, or phenocrysts, visible within the granite of James Hector’s monument match those in Douglas Hector’s gravestone. Part 2 of this article series explores how author Parkin traced their origin to a quarry in the Fraser Canyon. Photo © TW Parkin.

Fading Legacy

Sir James Hector wasn’t Canadian, and perhaps this explains some of the poor recognition of his name in this country. He was already being forgotten when American Mary Schäffer revived his deeds after meeting him. She then privately took on publicity in heartfelt empathy with her hero’s loss.

Today the CPR has forgotten his contribution to its success, but outdoor adventurers and rail historians can still wend the routes of his exploits using this article.

Passenger trains once stopped here, allowing passengers to visit the divided stream and Hector’s monument. Time after 1930 seemed to speed up. Today, the site is neglected and damaged. Postcard 14311, Peel Library collection, University of Alberta.

Loss of historical memory is an unfortunate part of our current era, but nor did Capt Palliser’s final report provide hope for future route finders. Palliser, as senior author, felt that passage through the Canadian Shield, as well as the western cordillera, was too onerous and that any railway would have to utilize American territory. This was even before that country’s 1869 completion of their own transcontinental road.

Hector left indelible marks on the landscape and in scientific knowledge of three countries. He was buried in 1907 in Lower Hutt, near Wellington, New Zealand, where he spent all of his married life, and is still respected for his advancement of that country. They, like some of us here in Canada’s west, remember him yet. Please consider a trip to the two monuments described as a way of making history come alive in a personal way.

Endnotes

- “James Hector.” Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Hector, as accessed 12 December 2020.

- Lakustra, Ernie. The Intrepid Explorer: James Hector’s Explorations in the Canadian Rockies, Fifth House Ltd (Calgary, Alberta 2007): pages 91-92.

- Erasmus, Peter. Buffalo Days and Nights, (Glenbow-Alberta Institute, 1976): page 77. The book was ghostwritten and first published 45 years after the author’s 1931 death.

- Schäffer, Mary S “Sir James Hector” Rod and Gun in Canada, vol. 5, #8 (January 1904): pages 416-418.

- Ibid.

- All Whymper quotes herein from pages 83-85 of his notebooks held in the Whyte Museum of the Canadian Rockies, Banff, Alberta.

- Lampard, Dr Robert. “The Hector memorials of 1906: tributes to Sir James Hector and Douglas Hector,” Alberta History, vol. 50, #4 (Autumn 2002): page 2.

Did You Enjoy This Article?

Sign Up for More!

“The Parkin Lot” is an email newsletter that I publish occasionally for like-minded readers, fellow photographers and writers, amateur historians, publishers, and railfans. If you enjoyed this article, you’ll enjoy The Parkin Lot.

I’d love to have you on board – click below to sign up!