Sleuthing on the Trail of Stone, Part 2 of 3 Finding a Forgotten Quarry

What happens to us

Is irrelevant to the world’s geology

But what happens to the world’s geology

Is not irrelevant to us.

We must reconcile ourselves to the stones,

Not the stones to us.

Finding a Forgotten Quarry

In Part I, Destination Disaster, I recounted the Canadian Pacific Railway’s (CPR) failed attempt to honour Sir James Hector’s discovery of Kicking Horse Pass. Before the ceremony, his son Douglas Hector tragically died of a ruptured appendix, forcing Sir Hector to cancel their trip.

Friends later sought to pay tribute to both men, salvaging the effort three years later with two carved stone monuments—unconnected but profoundly significant.

My interest in this story was driven by my life in British Columbia, my passion for railway history, and my background as a stonemason.

Before 1917, trains rumbled across steel spans supported by this row of masonry piers over Loop Brook, Glacier National Park, BC. The one on which the author (in green) sits was undermined by water erosion. Note how its fracture occurred in planar fashion, matching the masonry bond. These stones were delivered by rail from the Cathmar quarry. Photo © MA Moffatt.

After identifying a link between these monuments, I began asking: where did the stones originate? The two were visually similar, but the surrounding geology didn’t match them.

Equally intriguing were the tradesmen involved: who were they, where did they come from, and how should we credit their role in this national achievement? Initial answers were elusive, requiring my combined knowledge of masonry, scientific investigation, and archival research to uncover the truth.

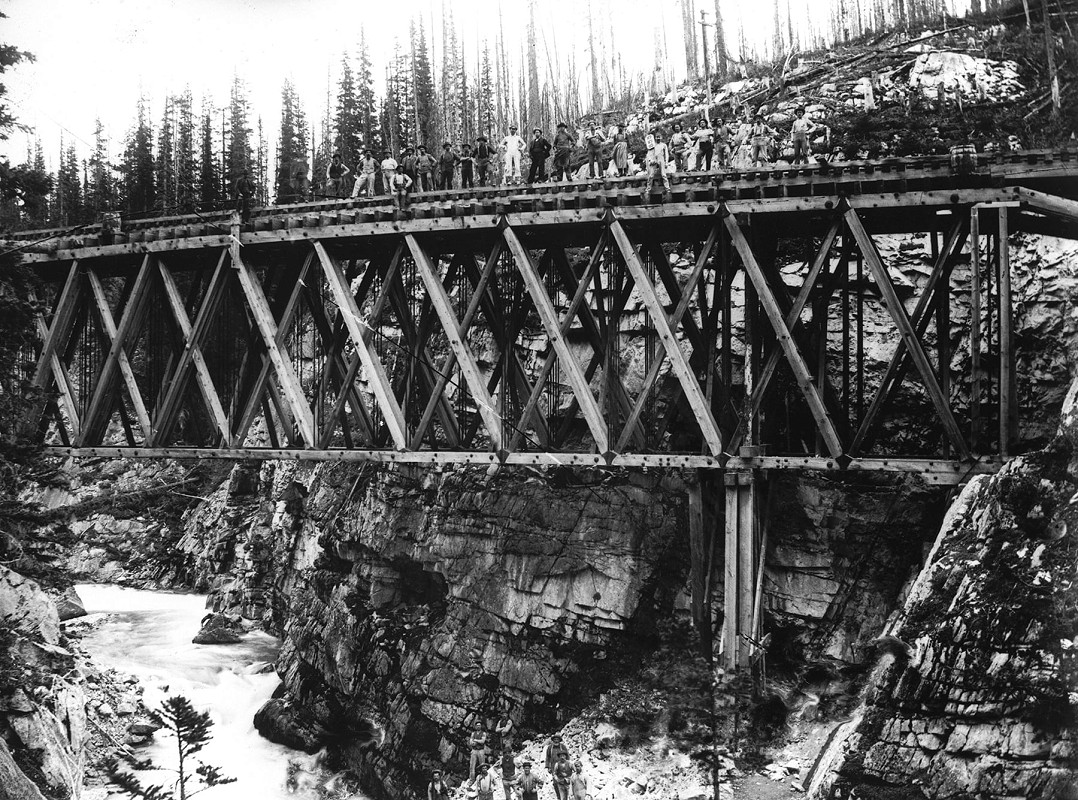

This is the first bridge at this site, once known as Crossing #2, meaning it was the second crossing of the Kicking Horse River made by the railway as it followed that river’s course westward. The structure is a Howe truss; it is not a trestle. Norman Caple photo, circa 1886. Vancouver Public Library VPL 14319.

The second bridge at “Second Crossing”, now in Yoho National Park, BC. Today it’s called “the old bridge”. The first timber truss here was built 1883-84. By 1898, this steel span provided improved support for trains. After the nearby Spiral Tunnels were completed in 1909, the deck was changed to concrete and the bridge used for road traffic. It is now abandoned. Photo © TW Parkin.

No Stone Unturned

Cascade Creek, east of Rogers Pass on the original surface route. This 1898 stone arch replaced timber trestles, repeatedly destroyed by snow slides. For 127 years, it has safely withstood the elements with enduring granite from Camp 16. Today, CPKC bypasses the summit via two lower-elevation tunnels. Photo © BE Gadbois.

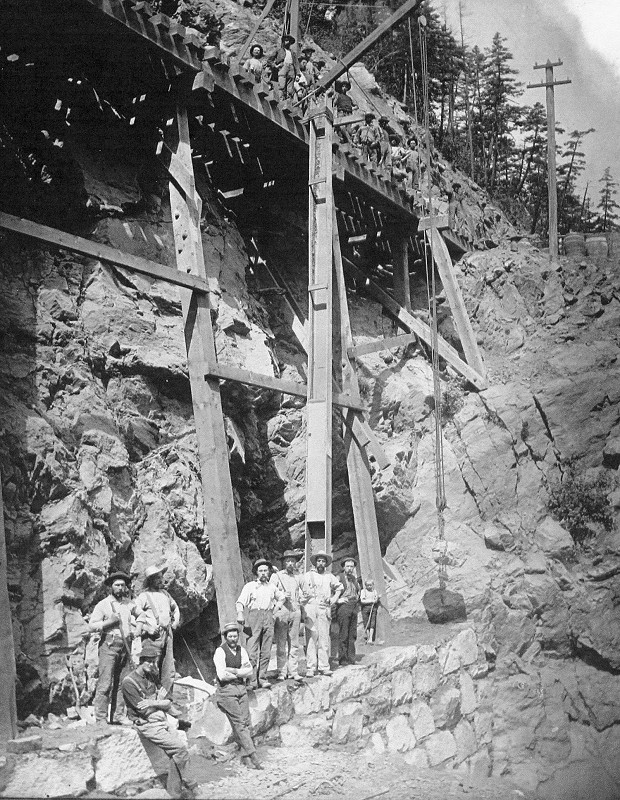

Eighteen masons (plus a boy) raising a substantial wall to replace a grasshopper trestle near Keefers, now roughly at CPKC Mile 110, Thompson Subdivision. This work is not as refined as that in the culvert construction I wrote about in my article, Building a Barrel Culvert. A steep chute directs mortar and backfill from above. Trueman & Caple photo, VPL 1025.

Mystery of the Quarry

Despite this preserved legacy, a key question lingered: where were these stones quarried? It was a senior railroader’s memory which set me on the path of discovery. Glacier Park staff, past and present, had no definitive answer.

A key question lingered: where were these stones quarried?

Vague suggestions nominated “the Canadian Shield” or “European tradesmen,” yet cost-efficiency suggests otherwise. The CPR, ever aware of budgets, would not have sourced stone from distant Ontario. It was once popularly known as the 'Cheapy R' for good reason!

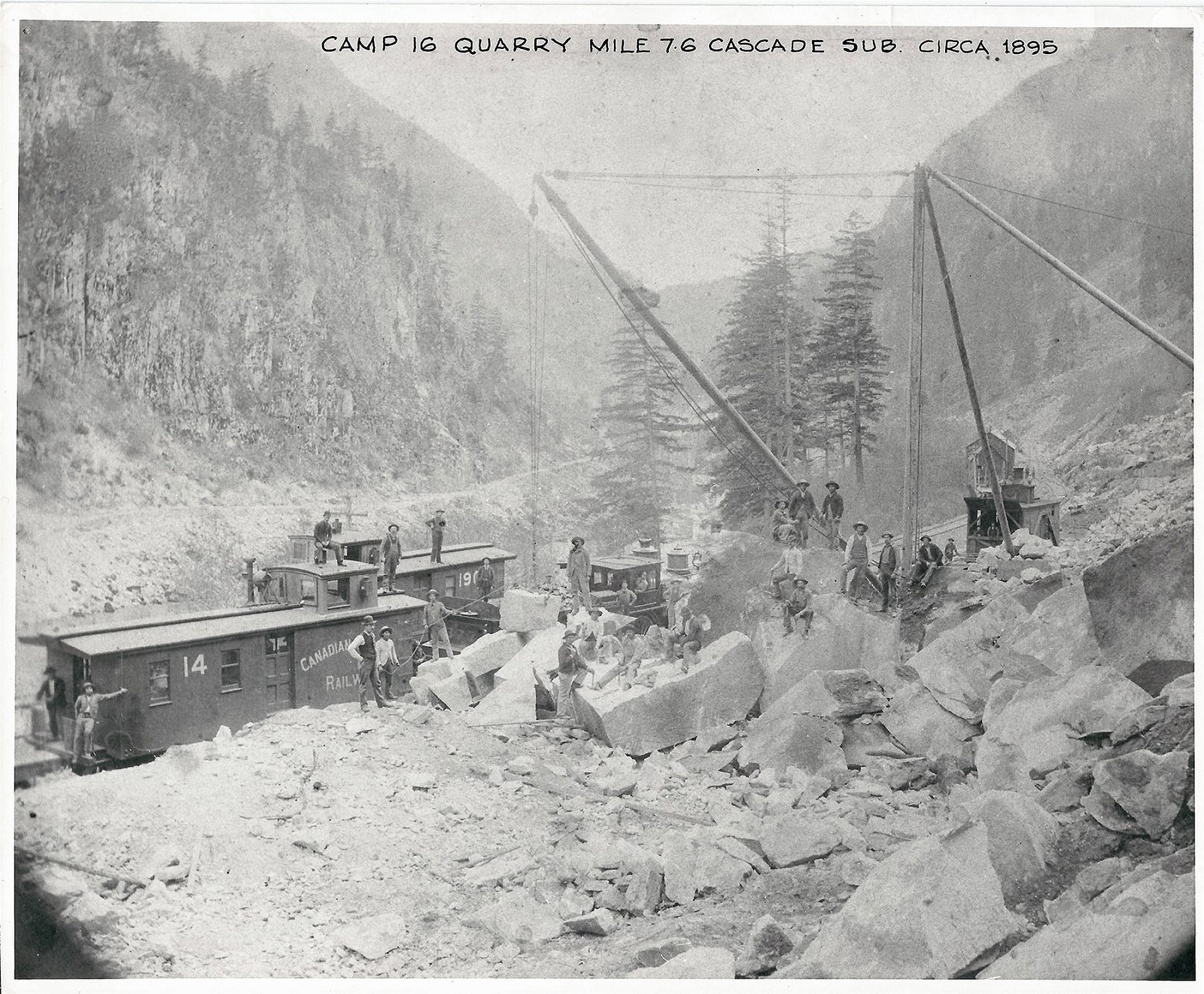

Camp Sixteen's mileage marks the distance from North Bend. The view is westward, capturing a 27-man crew shaping and loading stone. Indigenous stone cutters on the largest rock are drilling holes with hand steels, preparing to split the boulder into precise, stackable blocks. Although much of the work was manual, a steam winch stands behind the crew. CP 377's assigned engineer, M. Riley, may be the one leaning out the window. Across the river, the Cariboo Road from 1862 is visible, also used by Andrew Onderdonk for transporting materials. Trueman & Caple photo, courtesy of the Price family collection.

My breakthrough came from retired railroader Ernie Ottewell, a pivotal figure in the Revelstoke Railway Museum. “Check for Camp Sixteen,” he advised. Though obscure, this lead hinted at a forgotten quarry. Initial research yielded nothing—no records, not even on BC’s official place names website.

My breakthrough came from retired railroader Ernie Ottewell.

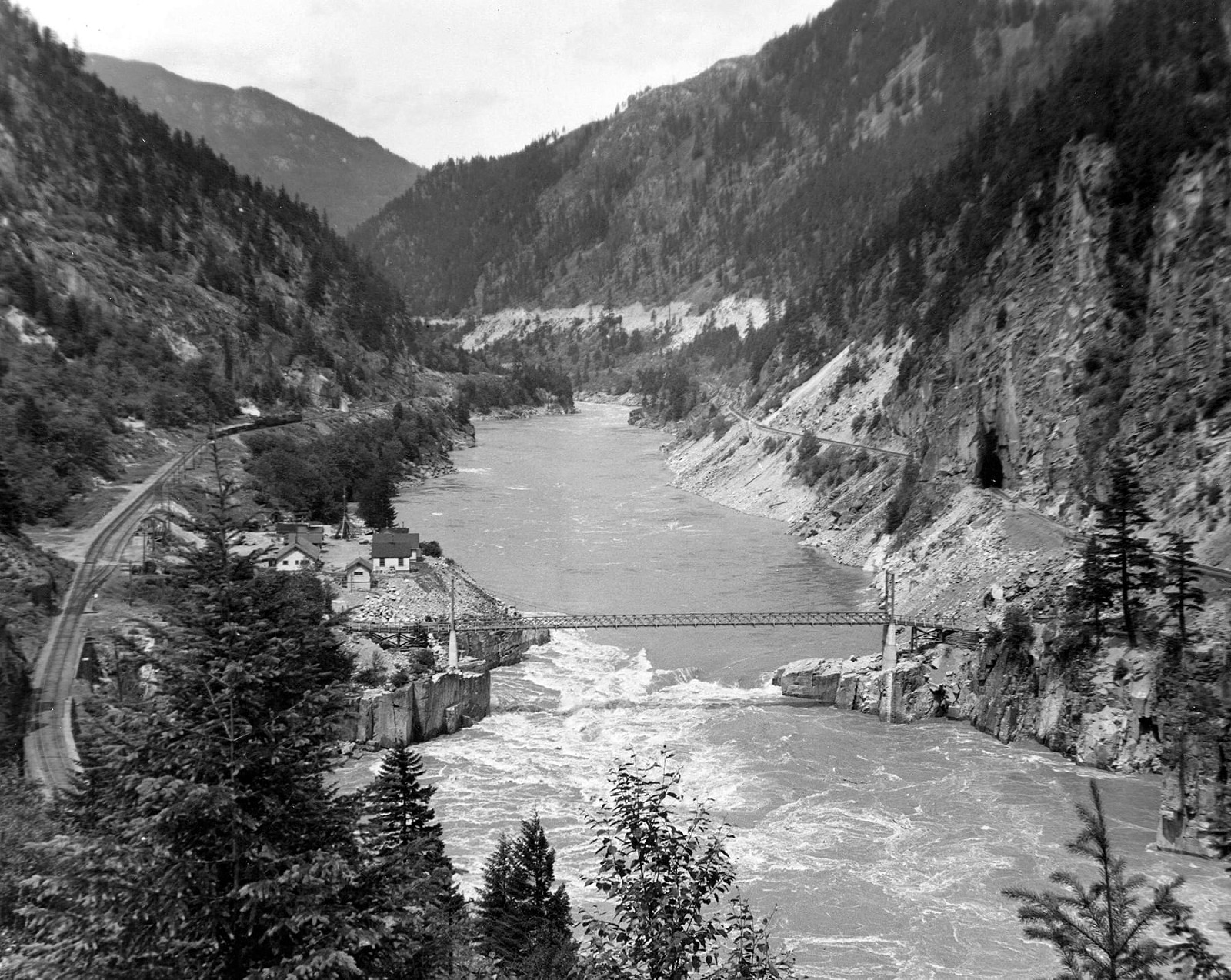

Later, I discovered “Cathmar” as another

name, only to find it was an old name for Hells Gate in the Fraser River

canyon. Camp Sixteen, Cathmar, and Hells Gate refer to the same constricted

section of the Fraser between the Coast and Monashee Mountains—a small

yet critical route.

Camp Sixteen/Cathmar quarry, located on the CPR main line between Spuzzum and North Bend, BC, operated until at least 1912. Compare how much material has been removed since the previous photo. Most of the quarried stone was used for culverts, retaining walls, bridge piers, and fill. The quarry spanned about 200 metres along the mountain above the railway. Two hand-operated derricks are shown loading flatcars, with more flatcars lined up in the distance. Upon closer inspection, the structures that appear to be tents are one-sided shelters, likely sun or wind screens for the four stone cutters named in Table 1. BC Archives G-05028.

The CPR’s western beginnings relied on segmental contracts awarded by Canada’s Public Works Minister. The first covered from Emory’s Bar to Boston Bar, a distance of 29 miles (46.7 km). Contractors tackled formidable terrain, requiring 14 tunnels in this section alone. Fortunately, the nearby Cariboo Road—built during the earlier gold rush—provided logistical support.

Contractors tackled formidable terrain, requiring 14 tunnels in this section alone.

Construction camp #16, just upstream from that road’s historic Alexandra Bridge, became the primary quarry for industrial stone.

Its granite met the CPR’s standards for durability and abundance. Determined to rediscover it, I traced remnants of quarrying amidst second-growth forests, confirming its location. Extraction ceased altogether about 1915, leaving behind ruins now overshadowed by nature.

CPR colour still shows on this dilapidated home with classic Tuscan red paint. Second-growth forest hides the site from the track, but within the trees, the ground is littered with industrial metal and domestic garbage. A family is known to have occupied the site (not necessarily this abode) been 1939-1944, decades after stone was last extracted. Photo © TW Parkin.

This large stone wall in a canyon on the Beaver River near Beavermouth, BC, replaced an old timber bridge first built in 1883. Interestingly, this narrow canyon was initially called Hells Gate until the more impressive restriction on the Fraser River became better known. JW Heckman photo dated 22 July 1899, VPL 856.

Rock of Ages

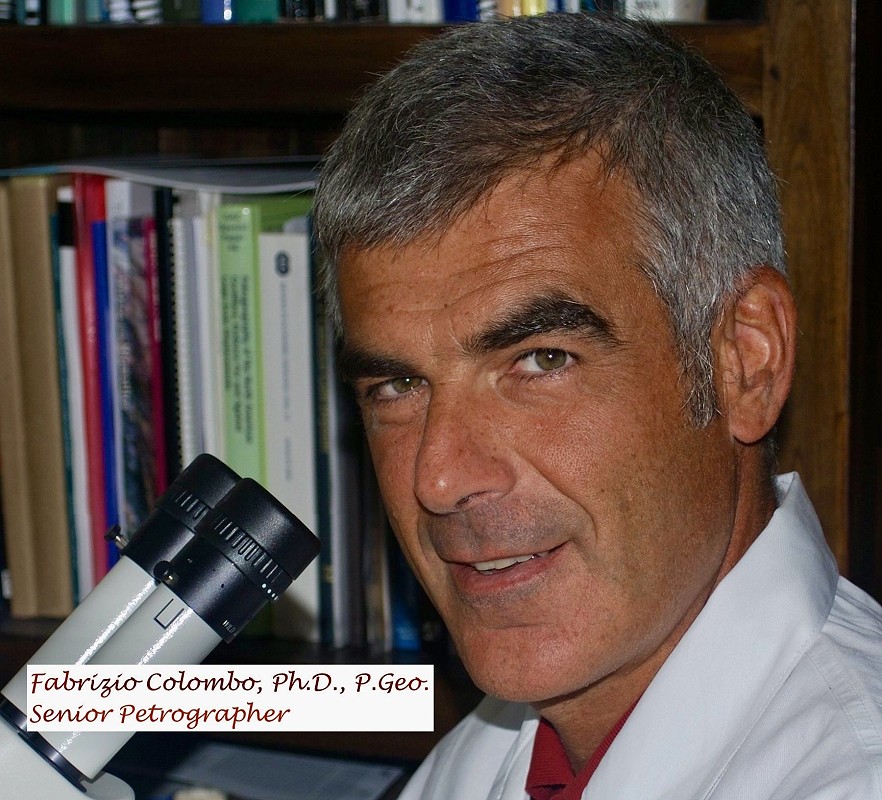

To verify Camp Sixteen’s role, I collaborated with Dr Fabrizio Colombo, a Vancouver petrographer. His analysis confirmed the quarry’s match to old CPR structures.

Yes, other CPR quarries did supply stone, but none matched Camp Sixteen’s longevity, distribution, or composition. This quarry stands as a crucial yet forgotten chapter in CPR’s construction saga.

In 1901, the CPR divisional point of North Bend had a population of approximately 275. It boasted a post office, telegraph and express offices, Fraser Cañon House (the CPR hotel),2 and Episcopal and Roman Catholic churches. From within the national census of that year I found these names, each identified as engaged in quarry work:

Extract from the Fourth Census of Canada2

Town of North Bend, April 1901

| Quarrymen arranged in sequence by descending age | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Status | = | Age | Origin | Year of Immig |

Occupation |

| Biansia, Louis | Lodger | W | 58 | Italy | 1881 | Stone cutter |

| Card, Silas | Lodger | S | 50 | Ontario | Stone cutter | |

| Lawson, Charles | Lodger | S | 50 | Sweden | 1891 | Stone cutter |

| Leigh, James | Lodger | M | 49 | England | 1897 | Stone cutter |

| Sharp, Sam Lee | Head | M | 46 | England | 1893 | Quarry labour |

| Riley, John | Lodger | M | 37 | BC | Quarry labour | |

| Turner, John | Head | M | 36 | Ontario | Quarry labour | |

| Sturgeon, Robert | Lodger | S | 35 | Ontario | Quarry labour | |

| George, Alex | Lodger | M | 32 | BC | Quarry labour | |

| Isaac, Peter | Lodger | M | 30 | BC | Quarry labour | |

| Bottle, William | Lodger | S | 30 | BC | Quarry labour | |

| Johnstone, Rich | Lodger | S | 29 | Italy | 1893 | Quarry labour |

| Pini, Achille | Lodger | S | 29 | Italy | 1900 | Quarry labour |

| Poluss, Daniel | Lodger | S | 27 | Italy | 1874 | Quarry labour |

| Barro, Elio | Lodger | S | 26 | Chile | 1898 | Quarry labour/painter |

| Poitti, James | Domes | S | 25 | BC | Quarry labour | |

| Christie, John | Lodger | S | 24 | Italy | 1899 | Quarry labour |

Who Were These Masons?

Nearby settlements of Lytton, Spuzzum, and Yale show a few scattered stone, but those in the above table constitute a core group, although known supervisors Edward Farr and Thomas Flann were apparently off site at the time. These 17 men at North Bend must also have travelled, to and fro on a daily, or weekly basis, to their quarry site, 12.4 km downstream.

I have not named these quarrymen in order of enumeration as a way of seeing patterns more easily. Note the eldest members hold positions of the most responsibility. We’ll never know his personal story, but widower Louis Biansia has been in Canada long enough to have worked on original CPR construction. He was among thousands of Italians who found steady work on maintenance of way gangs, and who never returned to their impoverished homeland.

So here again we find Canadians, not immigrants, engaged in railway masonry.

Also specified on the original pages of the census is that all those born in BC are aboriginal. These are mostly men of the Stó:lō nation, the dominant tribe of the lower Fraser River. The first local man which contractor Andrew Onderdonk hired was indigenous. Natives often participated in free enterprise in those days, and supervisors noted their good effort. So here again we find Canadians, not immigrants, engaged in railway masonry.

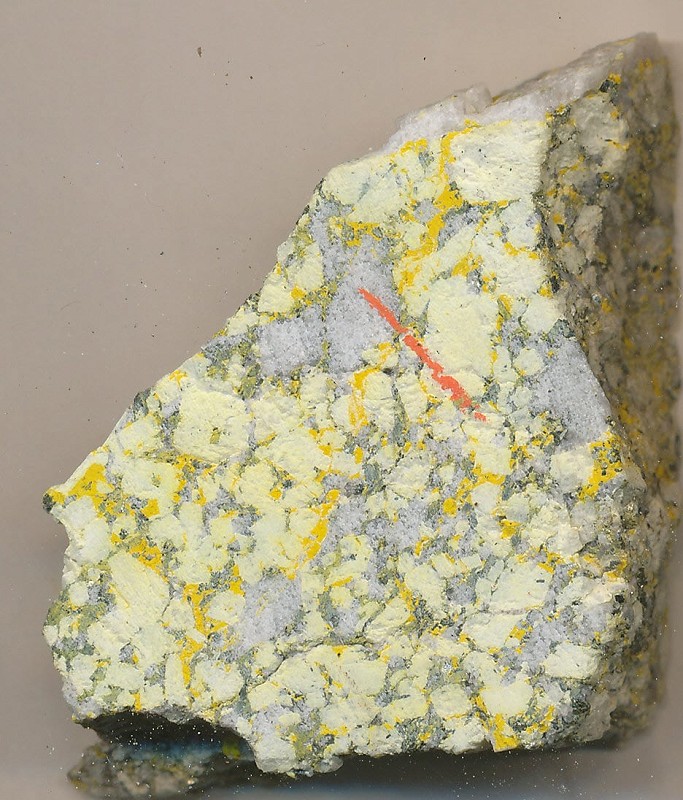

Onderdonk may have thought of shamrocks upon finding boulders like this in the talus beneath the cliffs at Camp 16. The lichen’s bright colour contrasts with the rock’s natural cleavage, forming fabulous rectangular blocks of consistent thickness. Minimal dressing could turn this rock into a strong structural element. Compare with finished stones in Photo 17. Photo © TW Parkin.

Most of Camp Sixteen’s crew are single—two even in their 50s. Two married men are marked as “heads of households” and live with their families. Every other guy lives in a company bunkhouse, hence his status as “lodger.” Silas Card is of particular interest, since he was seconded for the contract to carve and place the stone memorials for the Hector family, discussed in my prior CP Tracks article.

In documents pertaining to his employment there, he is described as a stonemason and he could well have had those skills, but at Camp Sixteen there is no assembly of product; Card is employed as a “stone cutter,” meaning he was transforming raw rock into stone ready to lay. He obviously had superior carving skills as demonstrated by his two monuments shown in Part 1.

Because mortar cannot be laid or cured at temperatures below 5°C (for risk of freezing damage), or in very wet weather, the period for laying stone is limited in the mountains. Thus it’s possible this crew was employed during the cooler months in preparing their own material at the quarry as a way of keeping them with the company, as opposed to finding and orienting new crew every spring.

These mostly anonymous masons built well over a century ago [...] deserve better—they deserve to be named and their effort properly attributed.

A way I was able to name another CPR stonemason was through the notebook of the early CPR engineering photographer, Joseph Heckman. He took a picture of a newly-completed retaining wall along BC’s Beaver River (in the Selkirk Mountains) on July 20, 1899.

In it, Heckman identifies one of a gang who stands apart from the rest, as foremen were wont to do. His name was pencilled as “Enrico Ender, Lytton, BC.”4

Searching for such a name at Lytton in the same 1901 census, I found him still there, only identified as Andrew Enrico, age 39, a Catholic stonemason of Italian descent. He isn’t new to Canada either; his wife Emily is a “Thompson River Indian”, and they have four kids, all born in the province, demonstrating the husband has been in Canada for at least 12 years. The seeming name difference can easily be attributed to a misinterpreted accent. A 1909 registration of death at nearby Kamloops, entered as Eurico Ender, is likely the same man.

In Part 3 of this series, I will delve into other sites where Camp Sixteen’s stones were erected into functional and beautiful works, how this work was done, and again, identify those responsible for their astounding craft. These mostly anonymous masons built well over a century ago—their talent and art now forgotten. They deserve better—they deserve to be named and their effort properly attributed.

Rolling Stones Forever

For decades, authors and authorities have vaguely attributed CPR stonework to Scots or others “brought over” for the job. I’ve long questioned these assumptions. Many historians overlook a simple yet powerful resource: Canada’s censuses, several of which are now transcribed and electronically indexed.

Here, I’ve demonstrated that half of Camp Sixteen’s workers were Canadian-born, and the rest had settled here permanently. There’s no need to defer our pride of place. These railway quarrymen and masons played a pivotal role during a transitional era—shifting from wood to concrete.

Their contributions deserve recognition, so need no longer be dismissed as a cost of progress or historical prejudice.

Taken 10 June 1949, this view is upstream, with the newly-constructed fish ladders hidden beneath high water. Now known as Hells Gate, the Cathmar section house is gone, and its siding is shortened. In the distance, a work train moves fill or ballast along the mainline. New fisheries offices and homes are on the opposite side of the CPR track from the overgrown quarry. Today, this flat area serves as the lower station for the Hells Gate Airtram, a tourist attraction accessed from the Trans-Canada Highway above the CN track on the right slope. CVA #Out755.2.

The quarry’s evolving name remains a mystery. When and why it became "Cathmar" after construction is unclear.5 Perhaps it combines two forgotten names—Catherine and Mary?

By World

War II, the name shifted to Hells Gate, an apt label emerging from the

years-long effort to build fish ladders around the 1913 landslide caused

by Canadian Northern Railway construction (today the CNR). This

disaster severely restricted salmon migration, transforming a vital

First Nations fishing ground into a battleground for survival.

Tom Parkin shows the 80-foot masonry arch built in 1899 over a dry gully named Jaws of Death. Its stone came from the CPR's Cathmar quarry on the Fraser River. Video © TW Parkin.

Yet, as the canyon’s geology crumbles, so too do the names that once defined it. Few today ask about its original Indigenous name, though it once provided a lifeline for cultures across the entire Fraser watershed.

My unconventional approach to petrographic analysis of historic masonry has earned recognition from two academics as thesis-worthy in geoscience. Wikipedia calls it 'forensic masonry.' To readers, I offer this: your own curiosity and ingenuity can also expand our understanding of railway history.

This 18-metre arch at Mile 8.1, Cascade Subdivision, near Hells Gate remains original despite a new safety railing and ballast lifts. Supporting modern train weights, it’s one of eight surviving masonry arches still in use along this section of the CPKC mainline. Replacement of aging original trestles with stone or steel began in 1890. Photo © TW Parkin.

Matching unused blocks left from construction of an abandoned CPR bridge pier (footing visible) which replaced a timber trestle over lower Loop Brook, Glacier National Park, BC. That alignment was abandoned in 1917 after recyclable materials were torn out. Where and how these structures were built will be discussed in Part 3 of this series. Photo © TW Parkin.

At the start of this article, Hugh MacDiarmid poetically reminded us that stone, though seemingly eternal, is ever in rebellion, yearning for stability.

The Big Bar landslide of 2019 into the Fraser again reminded us how fragile both geology and salmon ecosystems can be.

It responds to gravity, inching downward in an endless cycle. Stone piers in Rogers Pass have been toppled by water and by avalanche; concrete has cracked under stress; and the CPR dismantled its stone roundhouses at North Bend, Revelstoke, and Field. The Big Bar landslide of 2019 into the Fraser again reminded us how fragile both geology and salmon ecosystems can be. Yet, the granite of Camp Sixteen continues its silent dialogue with those who shaped it and the CPR that employed them, its legacy etched into British Columbia’s ever-shifting landscape.

In this ongoing conversation between stone, history, and human ingenuity, we find a reminder that even the most enduring structures require care, and that curiosity—whether in railway history or the natural world—can illuminate paths to preserving our shared heritage for future generations.

Endnotes

- Parks, Dr Wm A Report on the Building and Ornamental Stones of Canada. Vol 5, Province of British Columbia, Ottawa, 1917. Dr Parks says the quarry was disused by 1912, but I have found Sessional Papers from Ottawa which imply it was again active in September 1915.

- This Spanish spelling was widely used by the CPR in 1904. The accommodation was later called North Bend Hotel.

- BC District Yale and Cariboo, sub-district Yale (West) L-5, pages 1-5. Microfilm T-6431.

- CP archives Heckman photo #1197, Canadian Railroad Historical Association, Saint-Constant, Québec.

- Inbound correspondence dated 5 May 1906 from L A Agassiz calls the site Camp 16. BC Archives file GR-0429, Box 13, File 02.

Did You Enjoy This Article?

Sign Up for More!

“The Parkin Lot” is an email newsletter that I publish occasionally for like-minded readers, fellow photographers and writers, amateur historians, publishers, and railfans. If you enjoyed this article, you’ll enjoy The Parkin Lot.

I’d love to have you on board – click below to sign up!