Tales Told by Old Rails Reclaiming Rails, Reviving History

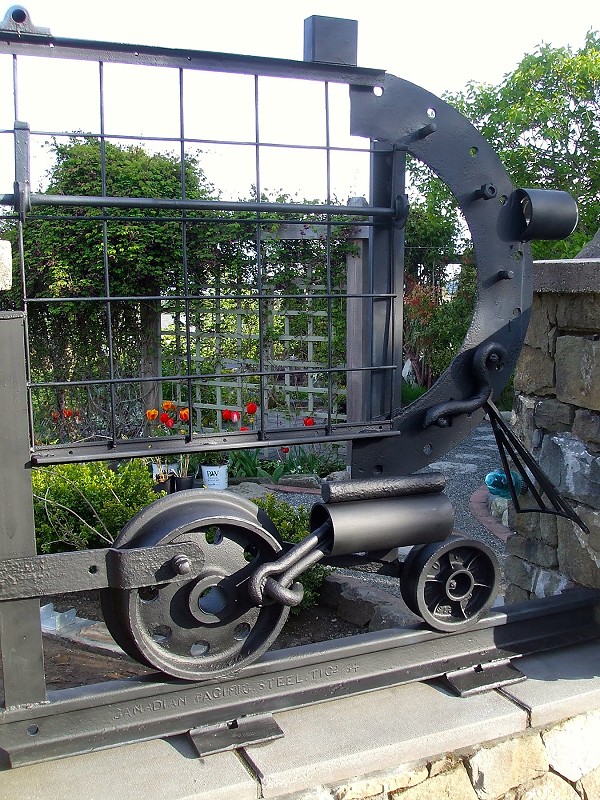

Steel rails are more than just metal across a map—they carry the wheels of history and of community connections. For me, they honour my late father, a locomotive engineer, and link deeply into Canada. In 2011, my interest in rails took a tangible turn when I found a four-foot length of rail at a scrapyard on Vancouver Island: Canadian Pacific Steel TI Co [18]84. It was a remarkable piece of history, likely transported around Cape Horn by sailing ship for use in the CPR’s westernmost tracks which weren’t completed until November 1885.

Discovering this relic sparked connections with others who share a passion for preserving such artefacts, whether as public art, private mementos, or historic records.

This maker’s mark TI Co 84 refers to the Tredegar Iron Company in Tredegar, Wales, Great Britain. Note the misspelling of Pacifiic, one of many errors likely due to poorly-educated foundry foremen. Photo © TW Parkin.

This article focuses on southern British Columbia, and on the years before the First World War. While some aspects of this history have been touched on by others, much remains unexplored. My hope is to provoke creativity, dialogue, and further research, expanding our collective understanding of Canada’s railway legacy.

In these days of declining budgets, space costs money and curators desire to improve the relevancy of their collections through documentation, judicious downsizing, or transferring materials to institutions where they are more relevant.

My hope is to provoke creativity, dialogue, and further research...

So-called amateurs, less restrained by purpose, policy, or procedure, can also take on a curatorial role. Railfans have already been doing this for themselves, and can often be directly helpful to museums. Our ideas can be unconventional, even occasionally objectionable to professionals, but I argue this is legitimate—representative preservation is better than melting all old rails as salvage.

Author Parkin notes discovery of an abandoned rail found on Vancouver Island. The branding reads Rhymney IIII 83. Rhymney Iron Company Ltd, based in South Wales, was incorporated in 1837. The vertical slashes denote the month of manufacture (June, 1883). Photo © JS Thorne.

Author Parkin kneels beside historic rail repurposed as a traffic gate and post. The branding reads Cammell Sheffield toughened steel 1884 E&N RR Co. This rail was manufactured specifically for the Esquimalt & Nanaimo Railway by Cammell of Sheffield, South Yorkshire, England. The railway was not completed until 1886. Photo © JS Thorne.

The Cultural Significance of Railway Memorabilia

Railway memorabilia offer more than a glimpse into the past; they are a tangible link to a transformative era in transportation and national identity. Items such as date-stamped timetables, branded china, or even vintage rails often hold layers of meaning.

These artefacts are valued not only for their rarity but also for the stories they tell—stories of technological innovation, personal journeys, and the evolution of communities across vast geographies.

For enthusiasts, these artefacts transform history from abstract dates and figures into something tactile, personal, relevant. Here are a few examples of what has been achieved in hope it stimulates projects elsewhere.

Garden art in a fence panel created by the author: a whimsical locomotive created from repurposed railway metal and glass, showcasing the utility of discarded materials. The larger wheel is from a CPR pumpcar. Photo © TW Parkin.

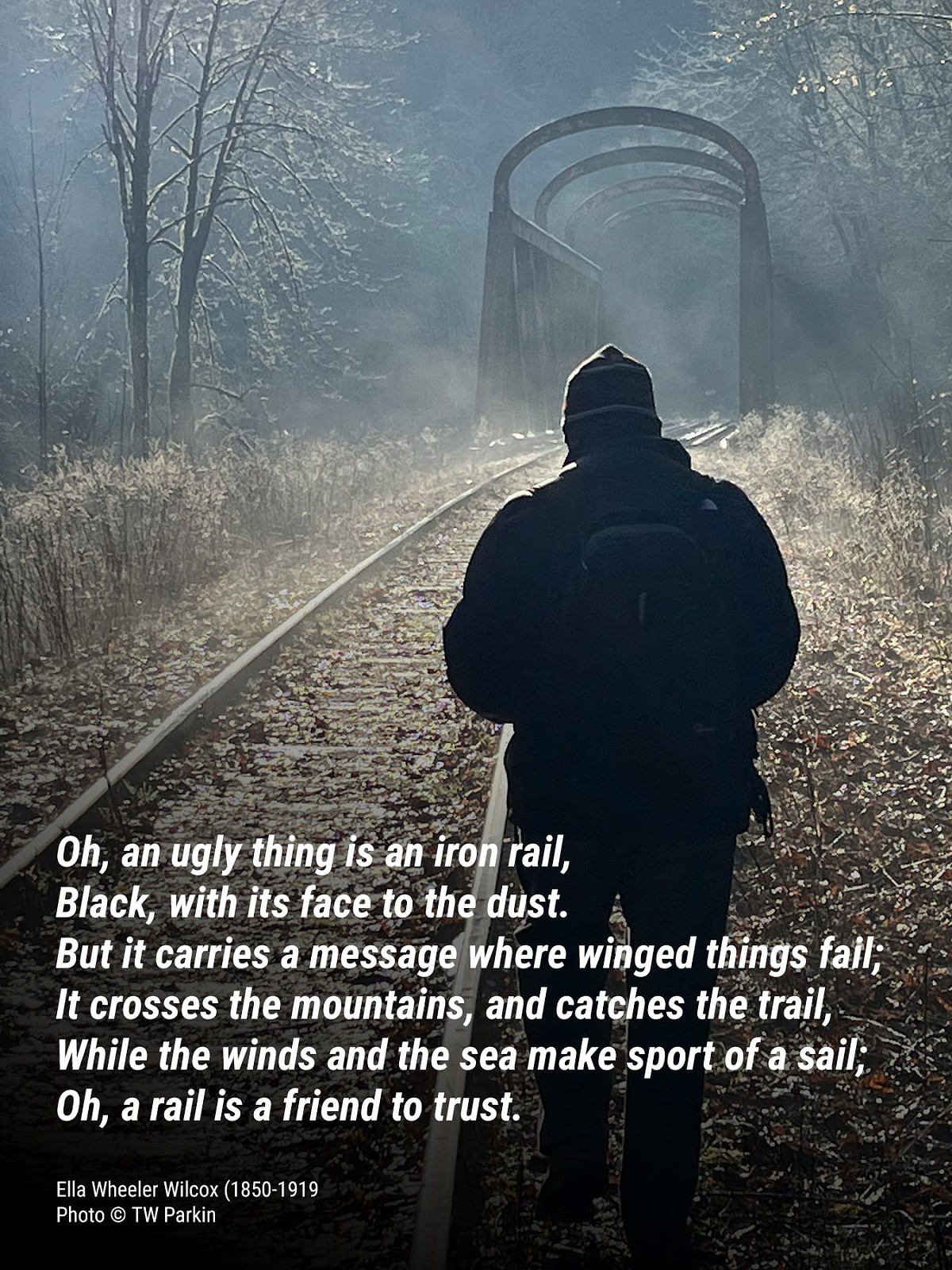

Walking over a defunct E&N trestle. The two middle rails are intended to keep a locomotive or railway car aligned should either drop off the outer rails, and thus reduce consequences. Such guide rails were often repurposed older, lighter rails no longer fit for regular use. Photo © TW Parkin.

Public Art and Culture

In 1988, the Town of Ladysmith on Vancouver Island received a national Heritage Canada Foundation award for exceptional downtown revitalisation. To commemorate this achievement, an interpretive display was installed on a prominent corner. Using industrial scrap from Ladysmith’s mining, railroading, and logging heritage, the display symbolises the community's progress since its founding in 1901. Framing the structure are steel rails dated 1883–1907, historic artefacts notably absent from the display’s signage but detailed in this article’s accompanying table.

Memorabilia

Railfans delight in collecting tangible connections to their passion, from locomotive photos to track segments. Even common spikes appear on Kijiji, often marketed as “valuable”. This enthusiasm is misdirected, but for former railroaders, a piece of track often represents a meaningful symbol of their career—especially when sourced from familiar lines.

Around 1973, a Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers local chairman in Midway, BC, salvaged disused Kettle Valley Railway (KVR) rail segments, gifting them as retirement mementos to union members. Management embraced this tradition as well, and many examples are still held by descendants.

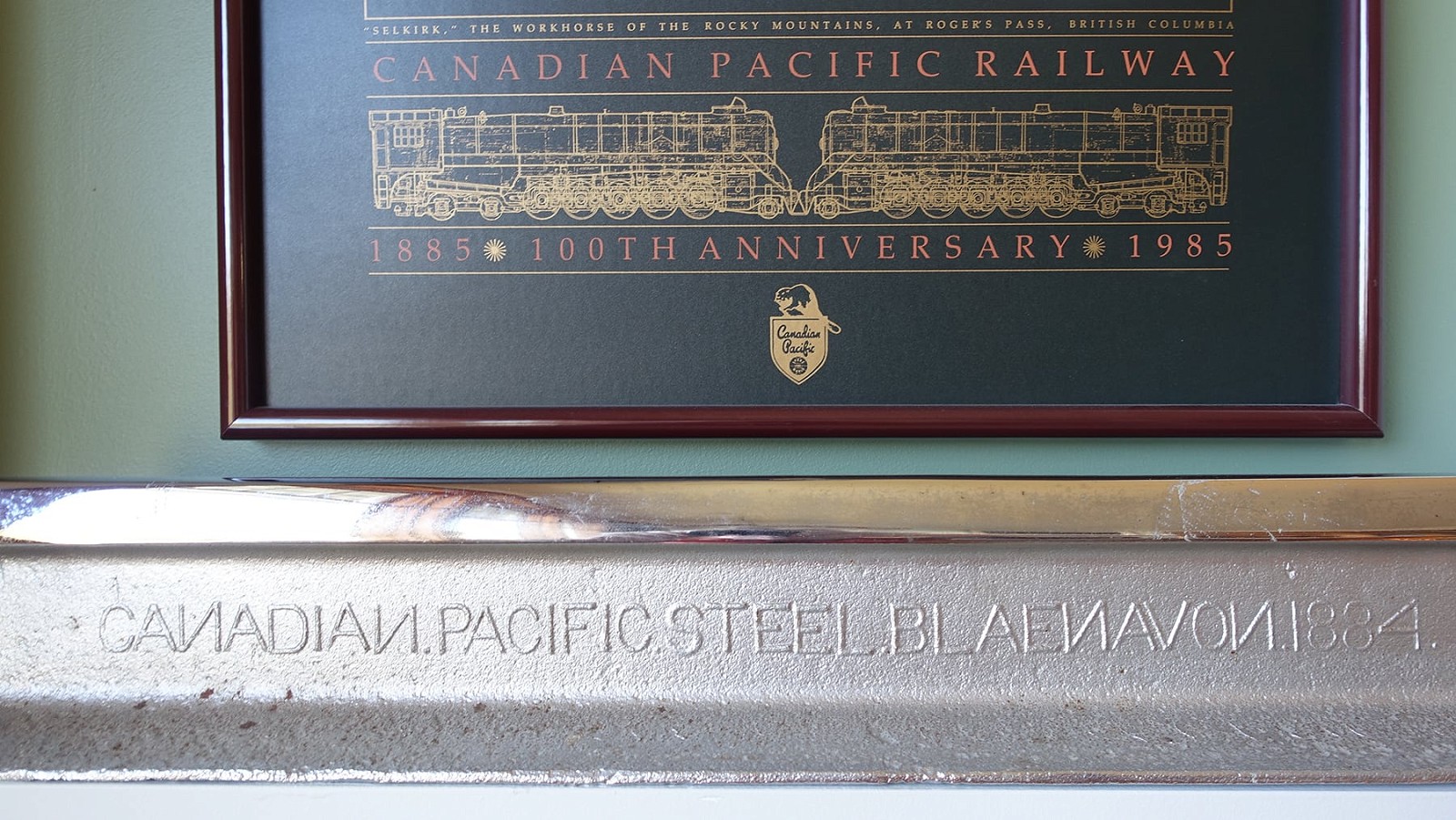

A section of chromed rail presented as a retirement gift for a CPR employee. Its provenance is unclear. In earlier times, section foremen were tasked with cutting out old rail segments for such purpose and shipping them to the Drake Street shops in Vancouver, where they were stored for such occasions. This rail was forged two years before the completion of its parent railway. Note the backward Иs. Photo © TW Parkin.

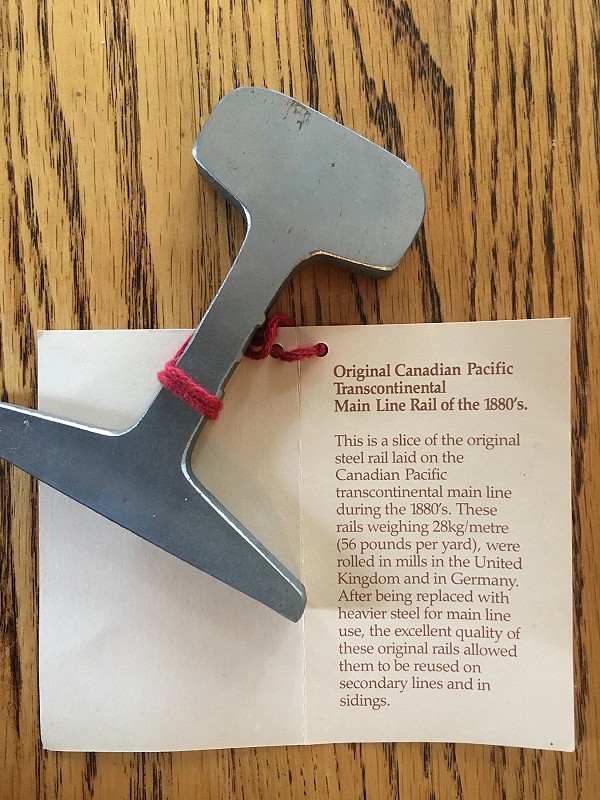

A polished slice of early 56-pound CPR rail, given as a corporate gift to attendees at the CPR’s centennial ceremony at Craigellachie, BC site of the Last Spike. Photo © RD Turner.

Compare the size of these modern rails to the early souvenir cross-section. Here, CP 8895 emerges from Tunnel #1 at Yale, BC, hauling empty coal hoppers. This track was originally laid by contractor Andrew Onderdonk in 1880. Photo © TW Parkin.

Similarly, during the CPR’s 100th anniversary at Craigellachie in 1985, polished rail cross-sections were distributed as souvenirs. The concept probably came from the late Omer Lavallée, CPR’s famed historian and a key organiser of the event.

These artefacts, often modified for aesthetic or practical reasons, differ from museum exhibits, which typically favour unaltered objects with intact branding for historical study. However, such keepsakes hold immense value for their owners as personal links to history and family legacy. Sadly, the provenance of these items is often undocumented, leaving their stories at risk of being forgotten.

Preservation

Most museum collections notably lack historic rail, likely due to perceptions it is too common, lacks historical significance, or is challenging to display and store. As a result, rails are sometimes preserved incidentally, serving as support beneath static locomotives or rolling stock. However, when displayed in context, such artefacts hold significant interest for railway and industrial organisations.

Modern museums, while appropriately selective about new acquisitions, sometimes overlook notable items due to a lack of expertise in specific fields or risk accepting replicas claimed as authentic. This practice risks “fake history” entering collections as authentic in the absence of experienced railroaders or rail historians for consultation.

During research for this article, I spoke with retired CP track worker Tony Rota, who owns a rail branded Oct 1885 West Cumberland Steel Canadian Pacific. He discovered it in 1985 during preparations for CPR’s centenary at Craigellachie, BC, unearthing four full lengths at the site of the Last Spike.

Rota’s accidental find unearthed a curious and fascinating blend of cinematic and railway history.

Did you catch that? The rail’s date—just weeks before 7 November 1885, when the CPR was completed—renders its presence there highly unlikely. The explanation lies in its origin revealed by more senior men. These replicas, made for the 1974 CBC TV miniseries The National Dream, were buried afterward to prevent confusion with original rails. Rota’s accidental find unearthed a curious and fascinating blend of cinematic and railway history.

Although not rare enough for museum preservation, Rota’s rail segment remains a cherished piece of private memorabilia. Its story—blending mistaken identity, cinematic history, and centennial commemoration—highlights the value of personal collections in safeguarding railway heritage.

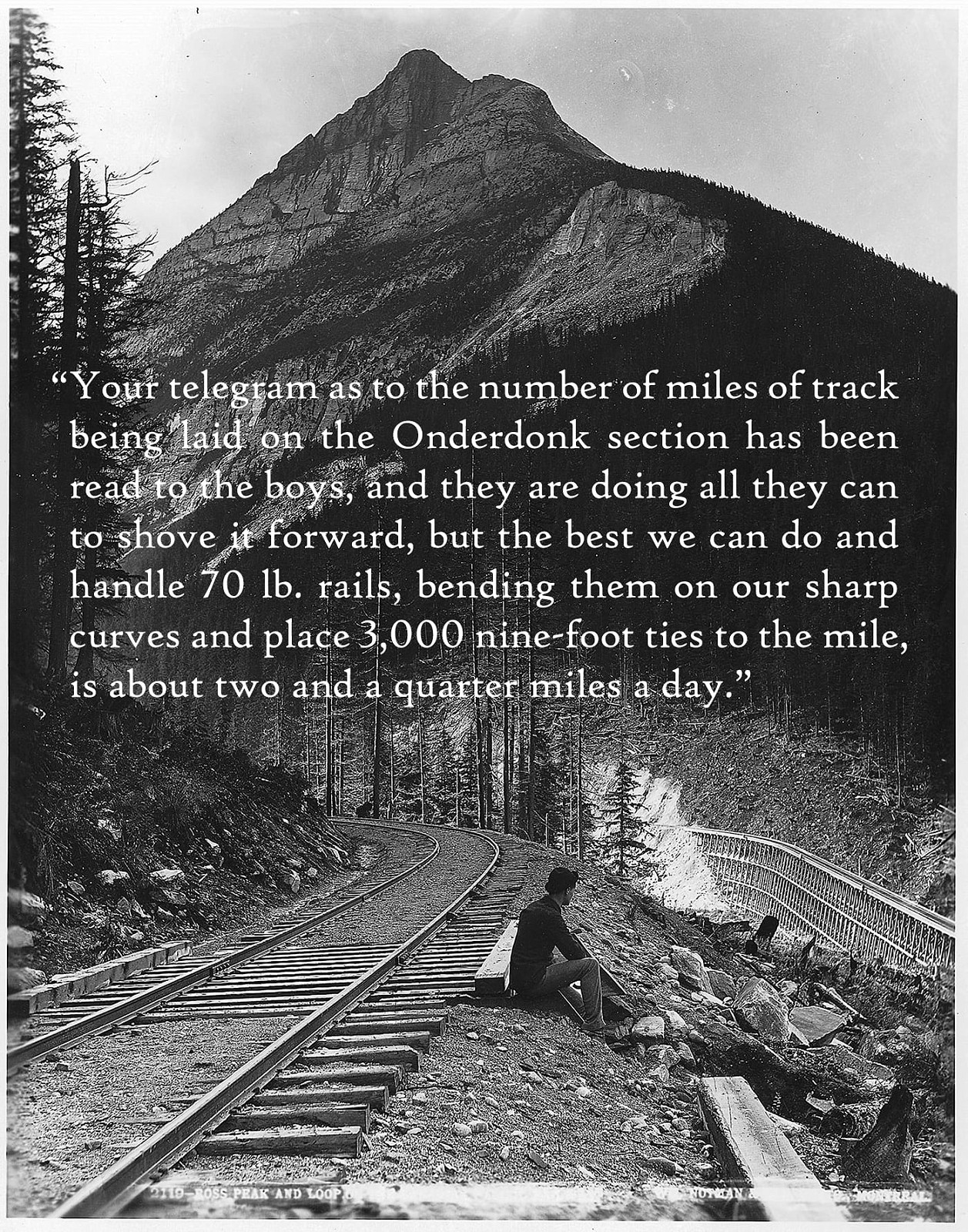

Thus wrote engineer in charge of mountain construction, James Ross. The summit in the background honours his successful solution of this steep climb over the Selkirk Range in 1884. Note his mention of heavier rail used for steep grades and sharp curves. Photo by Wm McFarlane Notman, McCord Stewart Museum, Montréal.

Recycled Use

Rail lifted for reuse elsewhere is called relay rail. Vintage rail replaced by longer, heavier steel is a natural progression in industrial evolution.

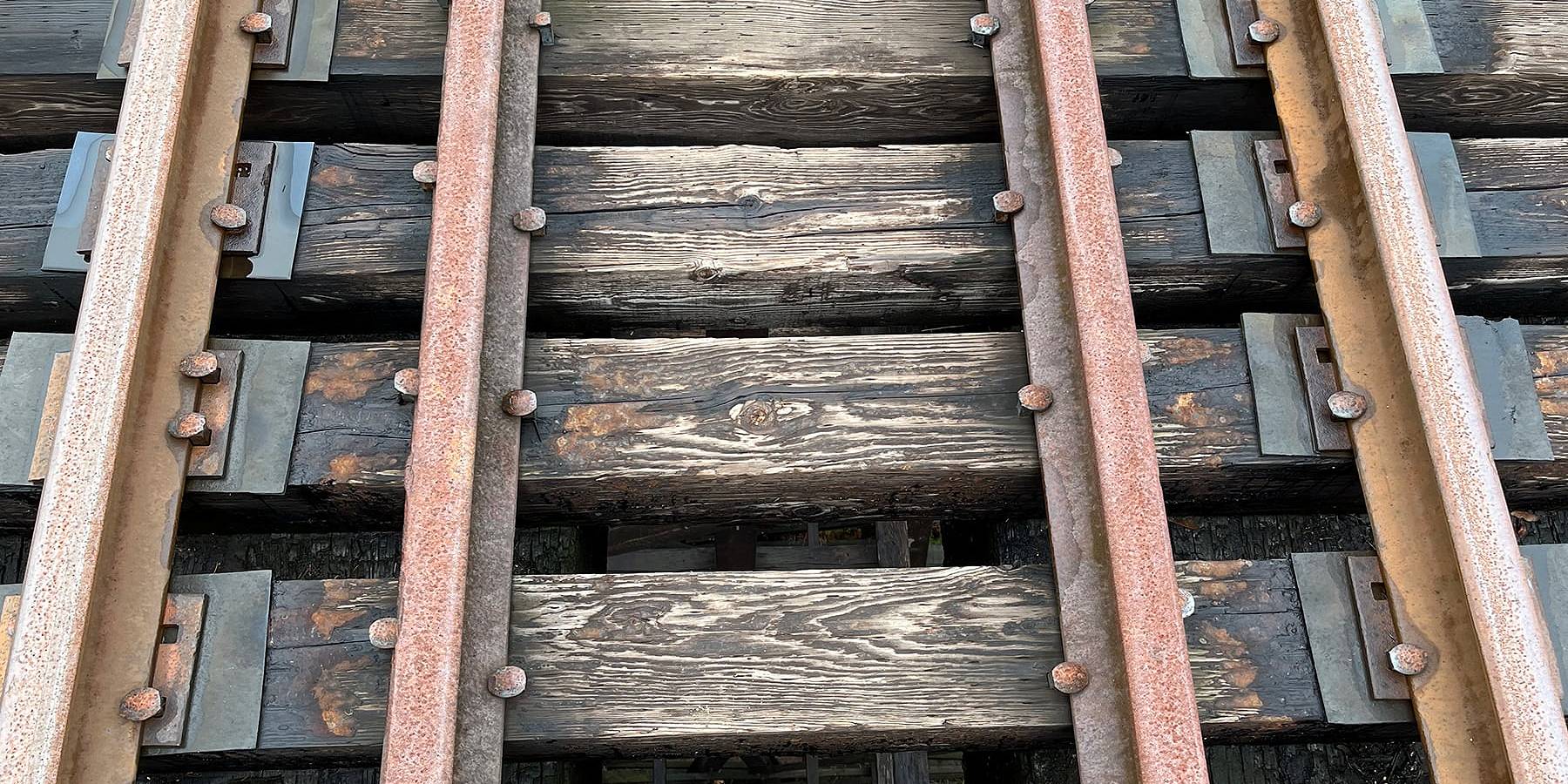

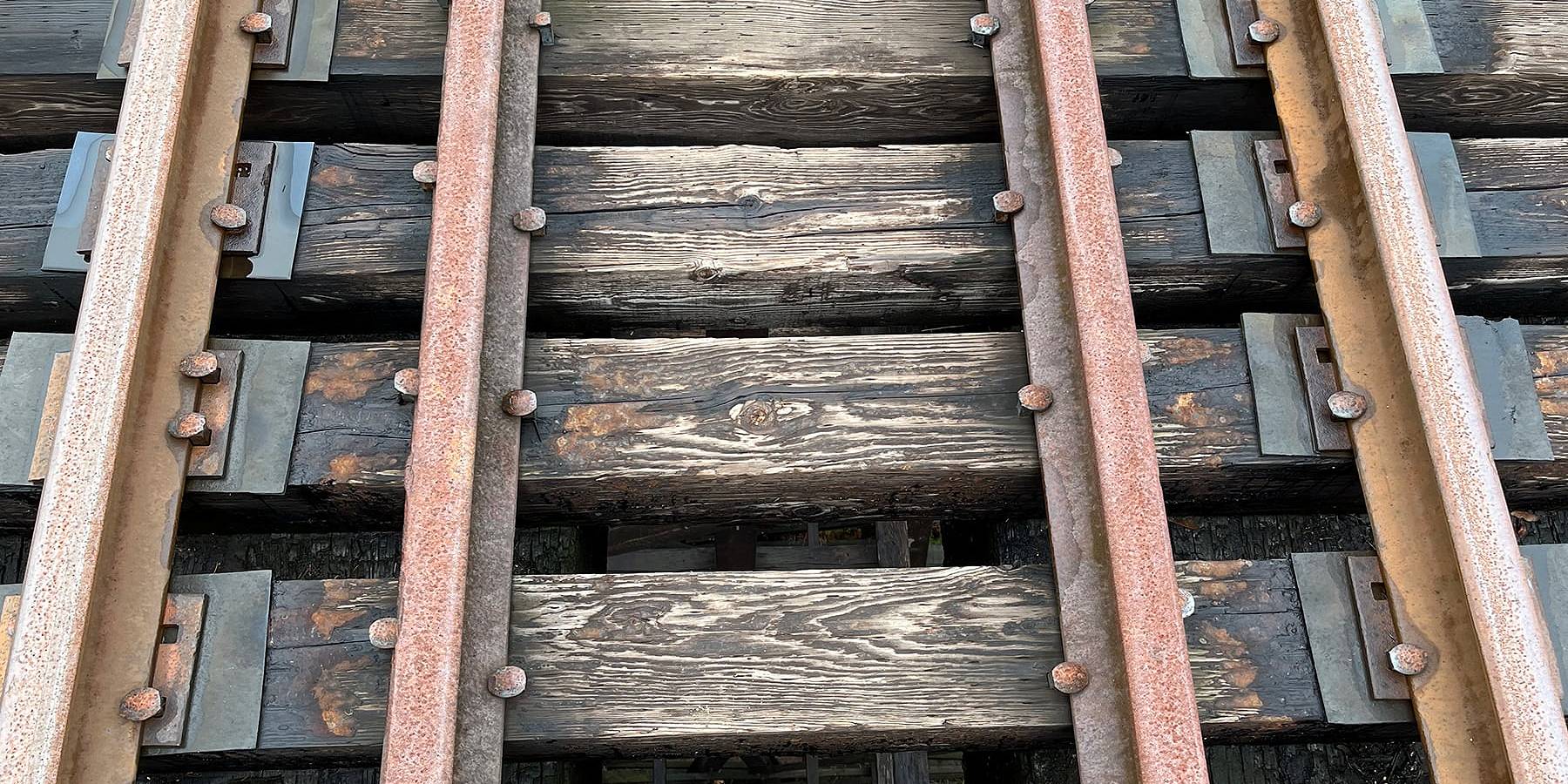

Relay rails are often reused on lighter-trafficked sidings, yards, or similar areas within the same railway system. If you’re searching for an old rail segment, those are good places to start. A wire brush, flashlight, garden shears, and sidewalk chalk will be handy tools to bring along.

Purchasing rail was also a political gesture to signal progress, though it occasionally backfired.

For example, the accompanying table shows rail from 1875 (line 17), likely first used in Ontario. Rather than bearing a railway’s usual initials, it’s marked PWC—Public Works Canada—indicating Federal Engineer-in-Chief Sandford Fleming ordered it.

This rail may have been laid through the Canadian Shield before the Canadian Pacific Railway was formally incorporated in February 1881. Purchasing rail was also a political gesture to signal progress, though it occasionally backfired.1

PWC 1875 was found in the CPR siding at Shepard, Alberta, on the Brooks Subdivision some 45 years ago. It likely followed the normal course of relay events and is now 150 years old, enjoying retirement in a BC home. The fifth-oldest, from June 1879 (line 10), shows no ownership marks. However, Fleming’s contract with the West Cumberland Iron and Steel Company (24 June 1879) promised delivery of 2,000 tons by August of that year.2 Such confirmation of origin is desirable should you go looking for formal provenance. This rail was likely first laid in Ontario, as the CPR had yet to form as a corporation, and contractor Andrew Onderdonk began his western construction only in May 1880.

The oldest rail yet discovered by the author: Panteg Steel Works & Engineering Co. Ld. IIIIII [June] [18]76. Its provenance remains unknown. Any cluster of dots or slashes as shown here indicate the month of manufacture. Photo © JS Thorne.

The Esquimalt and Nanaimo Railway (E&N) was built from 1884-86, too early for used Ontario rail to be moved west. However, after the CPR purchased the E&N in 1905, it expanded the line significantly. For instance, in 1910, the CPR relocated a cantilever bridge from its Fraser River crossing at Cisco to Niagara Canyon on the E&N near Victoria. Though inadequate for modern traffic, the bridge still stands today. By extrapolation, it’s plausible that West Cumberland 1879 rail was relayed to the E&N early in the 20th century before being taken up again. Fittingly, this length now carries steam trains at the Forest Discovery Centre in Duncan, BC.

Today, vintage rail is available for purchase online.

Old rail has been reused creatively worldwide. Examples include its use as rebar in the former Revelstoke roundhouse foundation, as fencing around a church in Alberta, and forged into an anvil in my family’s household—likely by a CPR blacksmith at my father’s request. Today, vintage rail is available for purchase online, with stocks advertised in many countries. This underscores the mobility of such materials, often passing through the hands of multiple companies.

In British Columbia, smaller logging and mining railways frequently acquired used rail from larger companies. Their uptake and relay were rarely documented, leaving museum curators with little to trace. However, museums increasingly focus on the stories behind collection objects.

Confusion also arises from unexpected discoveries, such as a 1884 E&N rail found in a cattle grid in Alberta’s foothills. Chris Doering noted his own discovery of a 1882 British rail atop the Pyramid of the Moon in Mexico: “[I] recently discovered . . . who knows where these . . . relics may be found. But that is what makes it all so interesting.”2 This underscores the dynamic life cycle of elder rails, where even the oldest can carry historical significance.

Old rail may be found on disused sidings or abandoned lines, in metal scrap yards, or used as steel for other purpose. This bridge was recycled from the Kettle Valley Railway to the Esquimalt & Nanaimo (both CPR subsidiaries) during upgrading of the former line in the late ’30s. The design is called a basket handle truss. Photo © TW Parkin.

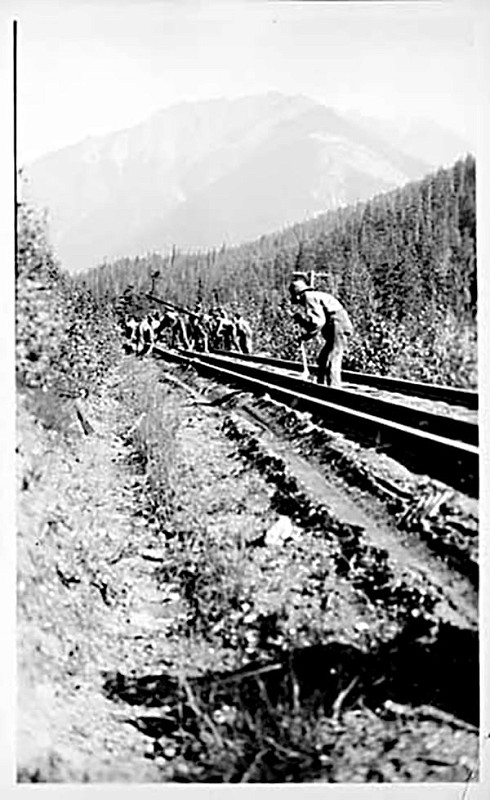

CPR track gang replacing 85 lb rails with 100 lb rails near Flat Creek, Mountain subdivision, BC, 1924. Vancouver Public Library photo #1744 with permission.

Interpreting Rail Branding

Rail branding today is far more detailed and standardised than the examples in the table below, reflecting international consistency in traceability and engineering specifications. Modern rail manuals detail steel compositions and placement records, but these are proprietary, with older documents now out-of-date. Below are selected examples from the table, offering insights to those documenting rail artefacts

A Short Census of Elder Rails in BC

|

Line # |

Year made |

Steel mill name |

Location of manufacture |

Additional marks |

Owner today |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1 |

July 1911 |

Algoma Steel |

Ontario, Canada |

85 lbs Sec 113 |

Midway Museum, BC |

|

2 |

Mar [19]14 |

DI&S Co. Ltd |

Nova Scotia, Cda |

850 |

Midway Museum, BC |

|

3 |

Sept 1880 |

Barrow Steel |

[England] |

C.P.R. 132 |

BCFDC, Duncan, BC |

|

4 |

1901 |

Cammell Steel |

[England] |

C.P.R. Sec 136A |

BCFDC, Duncan, BC |

|

5 |

Aug 1913 |

Carnegie |

[Pennsylvania US] |

ET 60A |

BCFDC, Duncan, BC |

|

6 |

[18]81 |

E.V. Steel [Ebbw Vale] |

[South Wales] |

C.P.R. |

BCFDC, Duncan, BC |

|

7 |

1888 |

Krupp |

[Germany] |

BCFDC, Duncan, BC |

|

|

8 |

Moss Bay Steel |

[England] |

Sec 81 56 lbs Per Yd |

BCFDC, Duncan, BC |

|

|

9 |

May 1879 |

Steel Co |

Scold |

CVP* |

BCFDC, Duncan, BC |

|

10 |

Jun 1879 |

W Cumberland Steel |

[England] |

BCFDC, Duncan, BC |

|

|

11 |

Nov 1884 |

W Cumberland Steel |

[England] |

Canadian Pacific |

BCFDC, Duncan, BC |

|

12 |

Aug 1907 |

Algoma Steel |

[Ontario, Canada] |

80 lbs |

Ladysmith, BC |

|

13 |

Jun 1883 |

W Cumberland Steel |

[England] |

C.P.R. |

Ladysmith, BC |

|

14 |

Jul 1890 |

W Cumberland Steel |

[England] |

C.P.R. |

Ladysmith, BC |

|

15 |

1885 |

Blaenavon |

[Wales] |

C.P.R. |

Private |

|

16 |

Apr 1875 |

W Cumberland Steel |

[England] |

PWC |

Private |

|

17 |

Jan [18]78 |

Cambria Steel |

[Pennsylvania] |

Private |

|

|

18 |

1884 |

Canadian Pacific Steel |

Blaenavon [Wales] |

[C.P.R.] |

Private |

|

19 |

[18]84 |

TI Co |

[Pennsylvania US] |

Canadian Pacifiic |

Private |

|

20 |

[18]82 |

Dowlais Steel |

[Wales] |

C.P.R. |

Private |

|

21 |

1884 |

Cammell Sheffield |

[S Yorkshire, Eng] |

E&N RR Co |

Bright Angel Park, BC |

|

22 |

Jun [18]76 |

Panteg Steel Works . . |

[South Wales] |

McLean Mill Hist. Site |

|

|

23 |

1884 |

Moss Bay Steel |

[England] |

Canadian Pacific |

RRM, Revelstoke, BC |

|

24 |

1883 |

Krupp |

[Germany] |

C.P.R. Steel |

RRM, Revelstoke, BC |

|

25 |

1885 |

STi Bochum |

[Germany] |

Canadian Pacific |

RRM, Revelstoke, BC |

|

26 |

Feb 1882 |

W Cumberland Steel |

[England] |

C.P.R. |

RRM, Revelstoke, BC |

Table Legend

- lbs = Rail has always been measured as pounds per yard. Old rail is usually lightest.

- DI&S Co Ltd = Dominion Iron and Steel, founded 1899; later became DOSCO; now defunct.

- [Square brackets] provide information not branded on that rail.

- Month of manufacture is usually shown as a dot cluster or row of upright slashes.

- Sec = cross-sectional proportions; the number following defines dimensions or weight.

- • = CVP unknown. No current or defunct North American railway uses this reporting mark.

- BCFDC = British Columbia Forest Discovery Centre, a museum near the E&N.

- RRM = Revelstoke Railway Museum. On the mainline of today’s CPKC.

- PWC = Public Works Canada. Federal Gov’t was builder prior to the CPR’s creation in 1881.

Line 17: Cambria Steel 78

This rail, found on a narrow-gauge logging railway near Cranbrook, BC, bears the name of the Cambria Steel Company of Johnstown, Pennsylvania. By 1878, Cambria was the largest steelworks in the United States. This rail likely arrived in BC post-1898 when Cranbrook connected through the Great Northern Railway. The logging railway may have sourced surplus US rail, illustrating how rail purchasers gradually transitioned from European to North American suppliers such as KVR samples at the Midway Museum. By the early 20th century, Canadian steel mills were offering the same product (lines 1, 2, and 12).

Line 18: Canadian Pacific Steel 1884

Blaenavon, Wales, once a renowned ironworking hub, lends its name to this rail, though no steel mill there operated under CPR's name or exclusively for it. Given that BC’s CPR contractor Andrew Onderdonk handled early rail orders, possibly he ordered rail branded with his client’s identity. The peculiar reversed Иs (see photo) suggests a foundry oversight. This error, visible on 1883 and 1884 rails, was corrected by 1885.

Line 20: Dowlais Steel 82

Dowlais Ironworks in Wales, once the UK’s largest steel producer, pioneered industrial steelmaking with the Bessemer process in 1865. This rail from the KVR was relaid 1900-14 and removed during abandonment in 1979-80. From the late 1930s to 1959, the CPR upgraded the KVR with heavier rails and reinforced bridges (see basket handle photo), bringing it closer to mainline standards. This highlights the evolving demands on rail strength and durability during the 20th century.

Thus we can assume some of this rail’s provenance. Possibly it first laid down on mainline ties during years of CPR construction and was pulled up during later upgrades, which were well underway by 1910. It could have found its second placement on the KVR, a CPR subsidiary. Where its companions went after 1980 is unknown.

Conclusion

Joint bars unite an unusual rail weight change from 85 to 115 pounds near Parksville, BC. Located at a E&N road crossing. Photo © JS Thorne.

This survey uncovered vintage European rail, some still in service, scattered across southern British Columbia but seldom showcased in museum collections. Industrial rail is a challenging subject for those outside railway circles to research and collect, yet it offers a rich area for further study and documentation.

Every rail tells a story—of its manufacture, transport, use, and survival.

Rails are more than artefacts; they are stories waiting to be told. Amateur historians play a vital role in uncovering and sharing these narratives, extending their reach beyond the railfan community. While mysteries will always remain, there is great satisfaction and purpose in exploring abandoned lines and preserving tales of our shared heritage.

When salvaging or donating rail artefacts, remember they gain value only when accompanied by provenance and thorough documentation. Record and photograph your discoveries to ensure they contribute meaningfully to the historical record.

Every rail tells a story—of its manufacture, transport, use, and survival. As stewards of steel, let us preserve not just the metal but the histories it carries, ensuring these connections endure for future generations.

Resources

Endnotes:

- Angus, Fred F “The 1879 Government Rail Contracts.” Canadian Rail no. 459 (July-August 1997): 102-103.

- Doering, Chris “Reading Rail: What do the Markings on Rail Mean.” Branchline vol 58, no. 6 (Nov-Dec 2019).

For further exploration, the following resources may be of interest:

- Rail writer and historian DL Davies saw old rails on the KVR and published his notes: Davies, David L “Explorations.” Canadian Rail no. 228 (January 1971).

- US Department of Transportation Manual; Track Inspector Rail Defect Reference (July 2015, revision 2): A comprehensive guide to industry practices.

- Maclean’s Magazine Archive; An early example of rail documentation: Cook, BB “The Rails that Wrecked the Government.” Busy Man’s Magazine, vol. XXI, no. 1 (1 November 1910): pp 41–42.

- Historic Rail Development; Overview and a brief list of defunct manufacturers via Wikipedia.

- Canadian Pacific Historical Association; Online documents, including track profiles detailing rail weights and placements for various subdivisions or locations.

Did You Enjoy This Article?

Sign Up for More!

“The Parkin Lot” is an email newsletter that I publish occasionally for like-minded readers, fellow photographers and writers, amateur historians, publishers, and railfans. If you enjoyed this article, you’ll enjoy The Parkin Lot.

I’d love to have you on board – click below to sign up!