Climate, Change, and Melting Ice

Few readers may have thought of railways as an indicator, a thermometer of sorts, of climate change in Canada, yet they serve as a historical gauge of winter severity.

In those days, lake ice was the only way to keep food cool.

This idea came to me when I was perusing the former activity of railways in the West, particularly their participation in the ice industry. It started with the CPR even before its line was finished through British Columbia in 1885. That era was without refrigeration as we now know it.

In those days, lake ice was the only way to keep food cool. As inventions advanced, railways adopted them; from ice storage facilities to designated insulated cars to transport fresh produce; then utilizing mechanical ice production. Finally, air conditioning and deep freezers were invented (including on transport trucks, with which all railways competed for a while).

Revelstoke icing crew, circa 1939. Left to right: Steve Bede (station gardener), Eli Kruy (labourer), ?, ?, John Sabo (extra gang), ?, ?, Charlie Godfreyson (extra gang foreman). Location is the icehouse siding, just east of the building. Photo courtesy Revelstoke Railway Museum.

This adaptation was simply the progress of technology, not a policy addressing climate, which was changing at the same time. In fact, the melting (or more accurately, retreat) of glaciers was first documented early in the 1900s at CPR’s Glacier House hotel in the Selkirk Mountains.

This adaptation was simply the progress of technology, not a policy addressing climate, which was changing at the same time.

They are the tag ends of the geological Ice Age; seen as phenomena without consequence because glacier ice wasn’t needed for anything other than scenery. At least, that’s what we thought back then.

This article is an overview of that period of change which might be called the human ice age.

Natural Ice Operations

Natural ice was once ubiquitous in homes and hotels for refrigeration, and was sold door-to-door. Homeowners used wooden iceboxes with galvanized tin interiors. Older readers may recall seeing them in the home of rural grandparents. A block of ice was held at the top of each box so cold air sinking from it would drift through a food compartment below.

Meltwater collected at the bottom, requiring daily emptying. Grocers and saloons needed large commercial iceboxes, while hotels and restaurants needed entire cold rooms for food and beverage preservation. This wasn’t only a warm season need, in other words.

Soon, entrepreneurs saw an opportunity to harvest free ice forming alongside the newly-laid tracks:

Recently an ice house has been erected at Texas Lake, near the steam powered sawmill, and under direction of Mr. Bacon a large quantity of ice is being cut for shipment [by steamboat] to Victoria in due season. The ice is about 14 inches and pronounced of a good quality. Here at Yale ice is being cut upon the side of the Fraser river near tunnel No. 1 and is about a foot thick. The Cascade House, California House and other public places, and a few citizens are packing for next summer’s use.

John P. Bacon was in charge of stores for railway construction, and may well have had the backing of prime contractor Andrew Onderdonk. Onderdonk's CPR construction was not yet finished at this time, so could he have been shipping materials for profit over the line while it was still technically in his control?

The City of Victoria rides at sea on Vancouver Island, and has a maritime climate. Rare is winter cold enough to freeze freshwater to any thickness. Sure, frozen lakes were known on BC’s ‘Big Island’, but they did not have easy transportation to the capital. Assume from this account that Yale, 200 convoluted miles distant from market, is the shortest, most expedient source, and it’s on the mainland, up a canyon.

Ice was typically stockpiled no later than March in those towns it was to supply.

Yale was a busy administrative centre for both the railway and local government. Texas Lake (known today as Klahater Lake), lies along the lower Fraser, 14 km downstream from Yale. Once CPR construction was finished in 1885, Kamloops became the largest administrative centre in the interior. Most everyone in Yale abandoned town, including the newspaper editor, and followed close behind the advancing track layers.

Klahater Lake had been chosen initially because it already had a rail spur for a sawmill; it had ready-made timber for construction of an storage facility; it had a lake which often froze to sufficient thickness; plus it provided sawdust from the mill, which was used for insulating the building and its ice stacked inside. Ice was typically stockpiled no later than March in those towns it was to supply. The Klahater Lake icehouse was built to hold 540 tons. However, as the railway built inland, so moved the ice harvest, to places where winters were prolonged:

Mr. Cambie [a senior official] having to go down the line, placed the C.P.R. ice supply in charge of Mr. C. Todd, who, Monday morning, had a force of men erecting an ice house along the track in rear of the Peterson building, a mile east of town. The size is 27 x 52 feet and two stories high. While the building was going up some ten teams were busy drawing sawdust from the mill and hauling ice from the [Thompson] river, where the ice plow and a number of men were at work. The teams and over a score of men made business look lively for some days. The ice is about a foot thick and of fair quality notwithstanding the lateness of getting it out. The weather was cool and cloudy, and favoured the work. Some 300 tons are already stowed away.

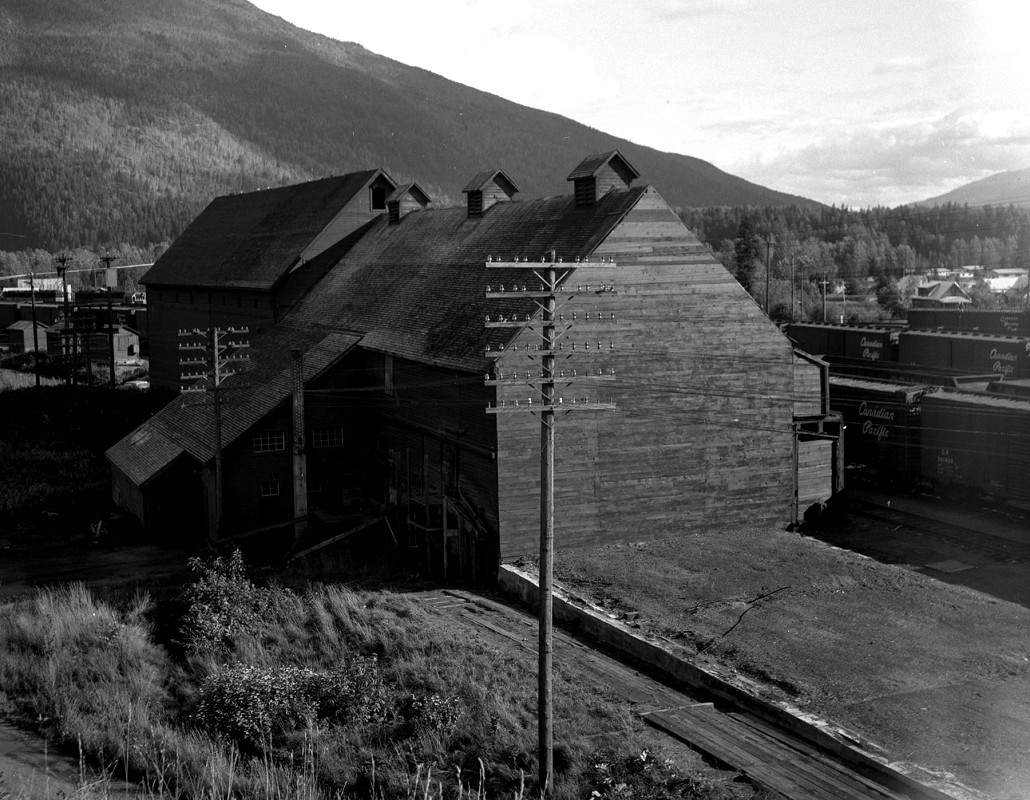

CPR icehouse at Revelstoke after a partial tear-down removed 60 feet from a 242 ft building. This structure was built here after 1929 (the missing addition in 1947) when a similar facility near the locomotive shops was demolished. Photo © 1970 David Davies, Northern BC Archives, UNBC accession #2013.6.36.1.016.47.

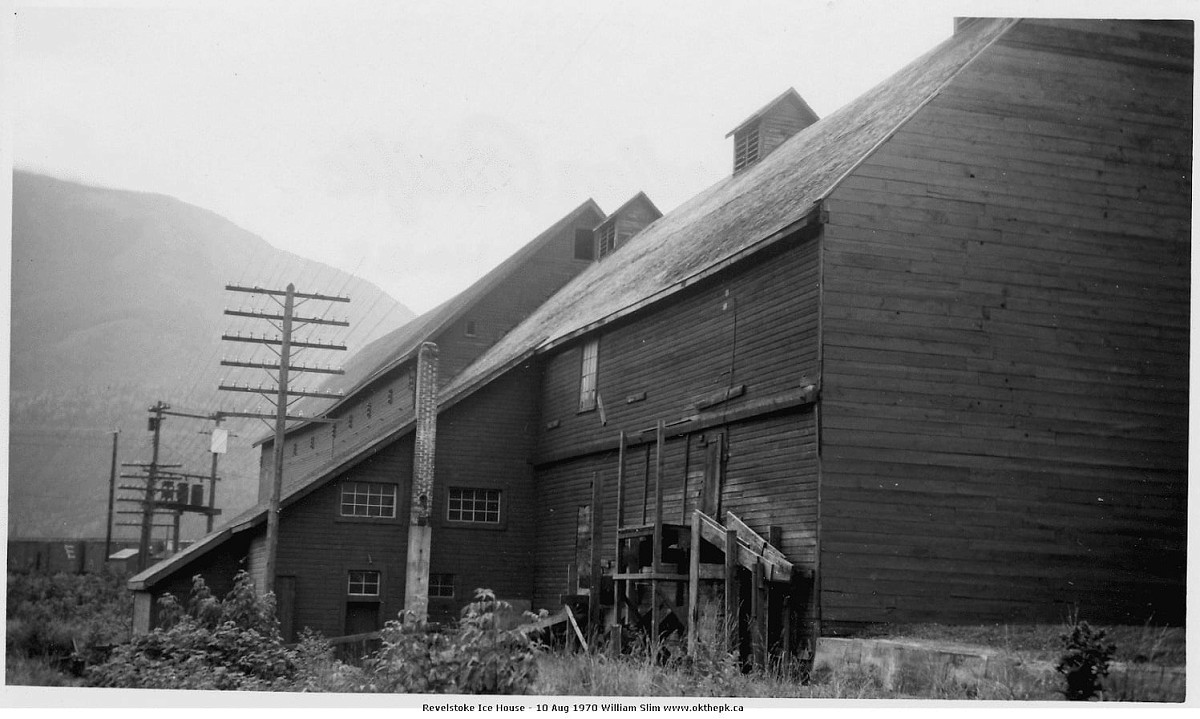

Back side of CPR icehouse at Revelstoke, BC, 10 August 1970. The concrete foundation and roofline shows how separate bays were added as demand required. Sometimes ice was stacked on bare soil since wood floors would otherwise need to support enormous weights. Photo © William C. Slim.

The 1200 tons which was usually cut on the Thompson River at Kamloops supplied CPR needs between Revelstoke and Vancouver. Private icehouses supplied the general citizenry. From this next newspaper extract, we learn that ice from the mainland was still being transported as far as the capital at a presumed profit despite several laborious trans-shipments:

The [paddlewheeler] Rithet brought down 100 tons eastern freight from New Westminster yesterday. Last night she took up a scow to bring down 100 tons of ice which was to have arrived at the Royal city last evening for the C.P.N. [Canadian Pacific Navigation] Company.

The railway now being complete, other enterprisers took over the ice trade. At this time, the CPN was privately owned, but it was purchased by the CPR in 1901. And of course, its galleys required a regular supply of ice all along.

Population growth meant larger harvesting volumes were needed around Kamloops because winters there are longer and cooler than at Klahater Lake. There was another climatic zone further east, but snowfall there was higher:

Thomas Costley has the contract for putting up 1700 tons of ice, nearly all for the C.P.R., and will fill the ice houses from Revelstoke to Vancouver. The snow in the mountains covers the ice too deeply and nearer the coast the ice itself is too thin. Four hundred tons will be shipped to Revelstoke, and Kamloops, North Bend and Vancouver will have their houses filled from here. The ice is only 10 to 12 inches thick, but is very clear and of fine quality. It is a lovely scene to witness about 25 men and teams at work on the ice field.

Designated Building

By 1892 icehouses were essential at all major terminals for servicing refrigerator cars carrying fruit and vegetables, meat, and other perishables. Such reefers needed to be refreshed at intervals, so icehouses were typically built at divisional points. They were as common as coaling facilities.

By 1892 icehouses were essential at all major terminals for servicing refrigerator cars carrying fruit and vegetables, meat, and other perishables.

However, some of Costley’s profits melted beneath his feet that same winter. Two months later the Kamloops paper reported local ice as too thin to cut, so Costley moved operations west into the Monashee Mountains. Technological developments also menaced his operations:

Isaac Harris of Tacoma proposes putting in a refrigeration plant at New Westminster [BC] to supply the four coastal cities with ice.

Artificial ice making was coming in, and eventually displaced the business of natural ice gathering.

Whether Harris’s proposal came to market isn’t known, but it did mark an evolutionary transition. Artificial ice making was coming in, and eventually displaced the business of natural ice gathering. It succeeded because it removed the vagaries of nature from outdoor harvesting.

It provided consistent quality (hygiene being one concern) and quantity, and meant seasonal supplies could be maintained. This also meant harvesting no longer needed to move inland or higher into the mountains, as seen at the Kamloops icehouse two year later:

T. Costley on Monday took up a team and four men to Three Valley lake to cut ice for the C.P.R. to be used from North Bend eastward in British Columbia. The company was apprehensive that it would not be able to have sufficient put up for requirements in all parts of British Columbia, so made arrangements with one of the cold storage companies to supply manufactured ice for Vancouver and points west of North Bend.

By this time ice was in huge demand, and Banff, Alberta (at elevation 1,400 meters the highest town in Canada) found itself in an advantageous position. It had the Bow River next to town, high winter unemployment, and less snow cover than either the Monashee or Selkirk Mountains:

Thirty-five cars of ice for Mr. F. McCarty’s [a Revelstoke butcher] cold storage has arrived from Banff and is being placed in the cold storage room.

Undoubtedly Banff shipped to Alberta markets as well. And, of course, the railway simultaneously supplied itself. By now, shipments were in the thousands of tons for any one icehouse:

The C.P.R. have this week stored their ice house with a supply of ice from Banff.

Technological Transition

Advertisements in the Kamloops newspaper for 1912 show domestic refrigerators being offered to local homes. Though slow to catch on, it was another ice pick to the heart of the industry, chipping off yet another market segment. Sales happened as slowly as glaciers melt, but really took hold in the economic boom following WW2. Kamloops cut its last natural ice in 1947 as the CPR switched to mechanical freezing.

Transport companies still used ice for cooling passenger cars, for fridges in their galleys (trains, ships, and hotels), and to keep commercial produce fresh during transport. The operation of refrigeration cars—cleaning, distributing, loading, all across the country, while maintaining a supply of ice, with a premium on timing for the volatile market value of the load—is an extended drama. The larger story, the history of making of artificial ice and refrigeration, is feature article in itself.

From its construction in 1911, Banff’s icehouse served passenger trains and refrigerated express cars into the 1960s. This unrestored building is now reserved for a proposed railway heritage site next to Banff station. Note its exterior siding of Insulbrick, a product with which the CPR once covered most utilitarian buildings. Despite the name, it had an R-value of only 1.3! It is rarely found today. Note the structural ridge beam used to hoist blocks to the second storey. The second floor is reinforced with iron rods to prevent wall spreading. Photo © TW Parkin.

Icehouse at Cranbrook, BC, 1974. This

building closely follows CPR standard plan #2, dated September 1914. The

original roof would have been shingle. Obsolete reefer 404432 sits

alongside. At one time, CP had 3,300 ice bunker reefers on its roster.

Photo © Robert D Turner.

CP 5902 heads east past Revelstoke’s icehouse, possibly in the 1930s. The building served for roughly 45 years; the locomotive only 27. Canadian Pacific corporate archives #NS.21326.

Icehouse Operations

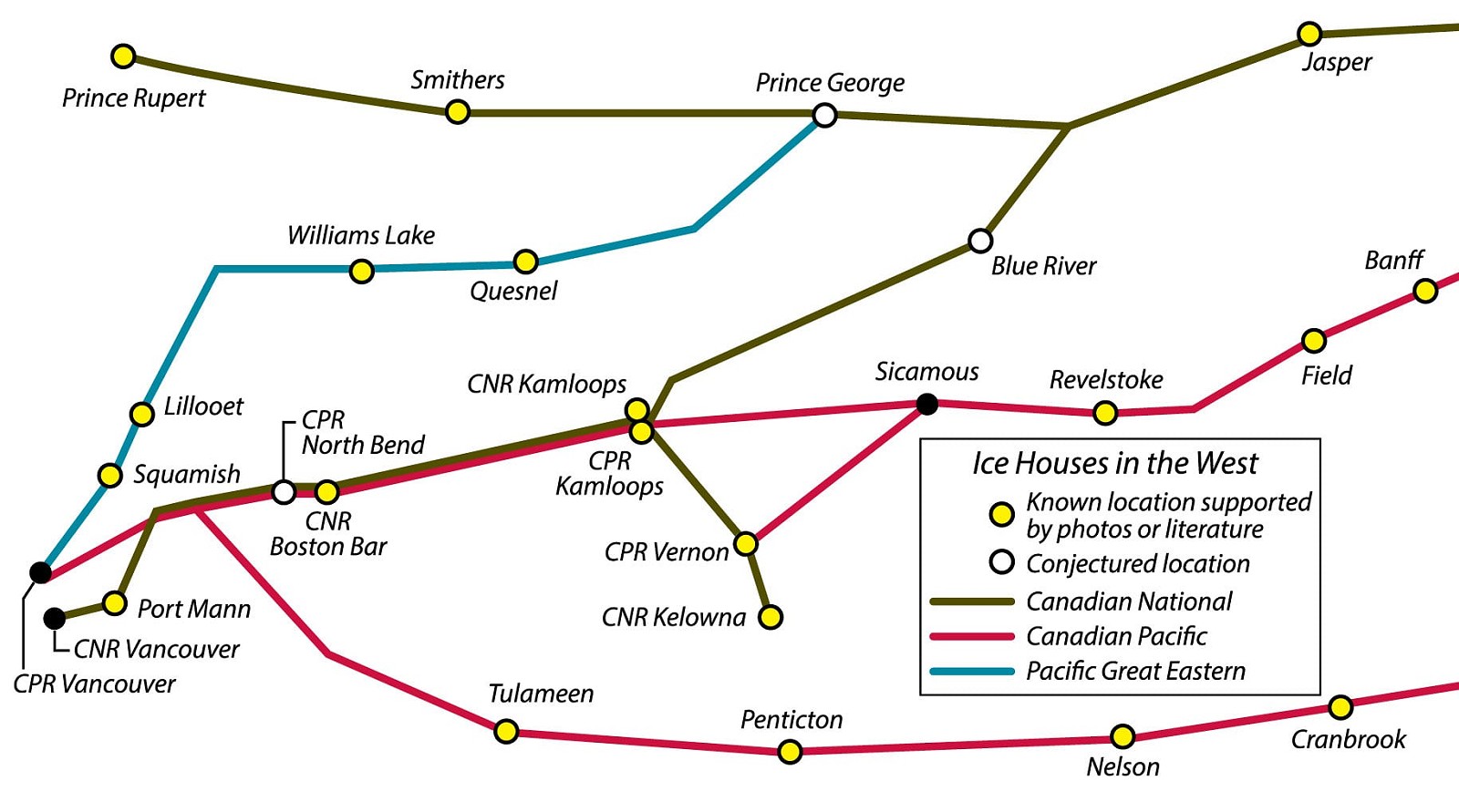

Storage facilities for winter-harvested ice (and later, machine manufactured ice) were typically built at railway divisional points, as shown on the below map. These were not always near the place of harvest because divisional points had permanent personnel and facilities needed for treating ice and transferring it to cars. Each railway developed its own methods, clients, innovations and designs, although all followed basic patterns throughout the age of ice.

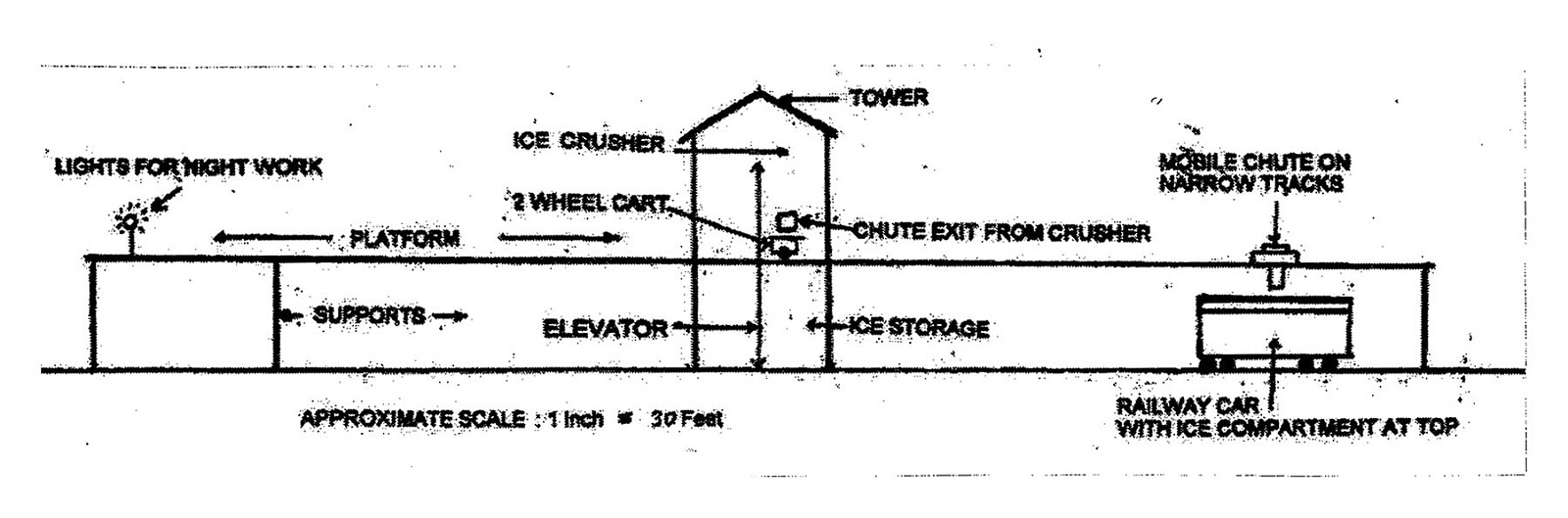

In this online reminiscence, a former employee describes his youthful experience in the CN icehouse at Kelowna in the early 1960s. A similar operation is shown in the photos below this quote:

[To start crushing], a workman using tongs would place a large block of ice on the elevator, which would take it up the tower to the crusher. The crushed ice poured down a chute which led to a platform at the roof height of waiting fruit cars. Other workmen then positioned a large two-wheeled cart beneath the chute opening. A lever controlled the flow of crushed ice into the cart. These carts were then pushed to the edge of the platform, where there was a pair of rails about 12" apart. A specially designed bin and chute ran on this track. It could be aligned with hatches on top of the reefers. Another hatch on the cart allowed ice to flow down this chute into the bunker of the rail cars. After all cars were iced, the string was assembled by a switch engine, set out for pick up by a freight locomotive, and sent to its destination.

Thousands of cars of fruit and vegetables were thus moved from BC’s Okanagan Valley; by CN to its mainline at Kamloops, and by CP to its mainline at Sicamous.

Icehouses needed insulated doors but no windows to keep out the heat.

Icehouses were simple timber structures with thick walls insulated with sawdust. Their ceilings were high—twelve, fifteen, or more feet. Interior walls were finished with fir, hemlock or spruce shiplap. Pine or cedar wood or their sawdust was not used because they off-gas scents easily absorbed by edible ice. Would you mind your G&T tasting like pitch?

Icehouses needed insulated doors but no windows to keep out the heat. They were often built in segments so storage space could be expanded over time without keeping a lot of dead air in a building. A CPHA library plan illustrating this article shows how simple they were.

Such facilities would be filled by the end of March during the natural ice era. The huge stacks were covered by blankets of sawdust. Sawdust was also layered between each course of ice, and between rows, to prevent the pieces from congealing into one massive block.

The icehouse I remember was in Revelstoke. It imposed itself inside the first curve east of the station, and was serviced by a 12-car stub track. Its hulking edifice showed few clues of its purpose. It wasn’t this divisional point’s original building, but was rebuilt here sometime between 1920-29 to make space for a longer turntable. Some have described it as “otherworldly.”

What I remember was that the main bottom area was cavernous inside, dark, and dilapidated, with high ceilings. I don’t remember any contents, but recall many chinks in the building envelope through which the sun crept, making dust dance in the gloom. When I worked on the ice gang—summer of ’56—we used to load salt into the upper part of the icehouse, bucket by burdening bucket, using a pulley system on the trackside. John Opra was in our gang.

Coach Icing

Icing of trains was routine business until the 1955 advent of the Canadian, the stainless-steel consist which was the CPR’s final attempt to draw dwindling passengers away from personal vehicles and new-fangled jet aircraft. The Canadian was mechanically air-conditioned, and the time saved by not icing its coaches (plus the introduction of diesel locomotives), shaved one night off its schedule between Toronto and Vancouver. Although refrigeration again brought change to the railway scene, even after the Canadian was introduced, up to 10 other trains a day still required ice for air conditioning and drinking water.

As a youth in a CPR family at Revelstoke, I recall the Dominion coaches being serviced in the mid-60s. Its coaches carried ice in undercarriage lockers. In summer, warm air was circulated through them while the train was underway, and the cooled air then fanned back up for the comfort of passengers.

Icing crews would wait for their anticipated train with carts loaded with 400-pound blocks, both on the station platform and on the second away from the platform. They positioned their product on flat handcars where need was anticipated. Platform crews used a tractor pulling a train of rubber-wheeled carts loaded similarly.

When a train came in, they had 20 minutes to ice the whole thing from each side. The rumble and thunk of those big blocks hitting the back walls remains in my memory. Where remnant ice wouldn’t allow a new block to fit, crews used ice picks and long-handled chisels to chip them to size. It could be dangerous work because of the need for speed.

Over on the Pacific Great Eastern at Squamish, BC, the late Hal Stathers still recalled his tasks:

During WW2 there often were not enough men to fill the service jobs so we teenaged boys were set to work. When short of help my father would call me to the coach track to get the train ready. This involved setting a ladder against the roof of a coach or dining car and filling the cold water tanks. The ladder was wood, and heavy, with a wide stance which was needed as it leaned against the slippery steel roof. I was instructed to be very careful to keep everything clean. Once a car had been watered, the rooftop ice locker had to be flushed, then loaded with blocks of ice. Once again the ladder was placed and blocks of ice made to fit in the locker were hauled in a bucket up the ladder and dropped in. Again, the demand was to keep everything clean including having every piece washed clean of storage sawdust.

Four ten-gallon bucketfuls were usually enough, which represented four trips up the ladder. Dining cars had two ice lockers. One was for milk, meat, and fish, and the other for potable use. Both took about four buckets. I was always careful with this job because if the chef was pleased, he might offer a small slice of fresh pie as a tip!

In January 1925, ice harvested from the Bow River at Banff is here being slid into CP boxcar 122706. It could be going west to anywhere in BC, or simply to Calgary. Photo by Byron Harmon, Glenbow Archives, University of Calgary, CU1155984.

Reefer Icing

Rail cars for freight also required ice, but for different purpose. Perishables needed to be kept cool from field or orchard to distant markets. Fruit from foreign countries was particularly vulnerable to spoilage due to its long transit time. When shipments of bananas arrived at the Port of Vancouver, large numbers of refrigerator cars were required and their produce was so valuable it would be accompanied by a human monitor.

Late CP conductor OS ‘Sinc’ Jones of Revelstoke remembered cars of green bananas accompanied by a traveller whose job was to ensure reefer temperatures remained optimal, and when fresh ice was needed during transit. Because these men didn’t get much opportunity to shop, and were provided no accommodation, train crews shared their caboose and sometimes their lunch box contents. In return, “the banana man” might offer bunches of fruit.

These reefers from the Santa Fe Railway are taking ice at Revelstoke with the assistance of the yard engine. Note the chutes used to slide crushed ice into the rooftop traps on the cars. Some which has overshot lies beside the car adjacent to the loco pilot. Nowadays, WorkSafeBC would throw the book at this activity, seeing the lack of fall protection. Photo courtesy Revelstoke Railway Museum.

Reefers were cooled with crushed ice dropped through roof traps into bulkheads at each end, which kept ice from touching any product. A ventilation system circulated air around the central produce to keep cooling even. A general rule was not to let the level of ice drop below that of the load.

Despite design innovations over time, such transportation was laborious. If reefers in a train required fresh ice, the procedure was to cut them out of a longer train and use the yard goat to push them in sequence along an icehouse siding, so a gang could pass along the rooftop catwalk, operating the chutes down which the ice passed. Fruit trains were sometimes 40 or 50 cars long, especially where CP's Shuswap and Okanagan branchline brought harvests to the mainline from cherries (July) through to apples (September).

I worked [Revelstoke] for one season—1966 or ’67. I recall we dragged 300 lb. blocks of ice from a huge stockpile to the crusher, then loaded the crushed ice into reefers from the Okanagan [valley].

Loading passenger trains was a frenzy, as pressure was on to be as quick as possible to keep its schedule. For a bunch of kids, I thought we did well, working as a well-oiled machine, especially coordinating the loading of the reefers, and tamping as much ice as possible into the top-loading cars.

Welcome to the Holocene

Welcome to what? Pardon my literary license. The Holocene is the era we live in right now. It means “entirely recent”. Geologically speaking, it means the Ice Age is over. Thinking big picture, that change happened so slowly few recognized it until climates got remarkably warm recently. The idea seems similar as I look back over the era of railway ice. I lived through its dying days, but youthful priorities prevented recognition of the changes around me.

John Opra worked at Revelstoke’s CPR icehouse 6-7 summers before starting a career as a schoolteacher in his hometown. In a telephone interview from Revelstoke, he told me:

“‘Good Lord!’ I wondered. ‘It’s the 1950s and we’re still doing this kind of thing?’” Opra was aghast at the effort of shovelling rock salt out of gondola cars for storage on the upper floor of the icehouse. The salt was later added to crushed ice when filling reefers. Salt has the effect of reducing ice melting point, so it lasts longer and thus requires less refreshment. All through CP’s “ice age”, young men easily gained employment for their physicality.

As late as 1954, ice was also needed aboard the last CPR steamship to ply the Arrow Lakes. Blocks were sent daily on a mixed train down the Arrowhead branchline for use in the galley of S.S. Minto. The Great Northern Railway supplied its BC boats from an icehouse at Mirror Lake, beside their shipyard on Kootenay Lake.

The CPR was benevolent in those days, and young men whose father already worked for ‘the Mother Corp’ easily found summer employment:

My favourite job was working at the CP icehouse, following in the steps of my father, his brothers and their father (my grandfather) who was killed on the job there, in an unfortunate industrial accident in March 1954. He was working as the plant’s stationary engineer when he fell down the elevator shaft. While working the graveyard shift, I would imagine he was up in the rafters watching me. Rather than being creepy, I found it comforting.

CP icehouse, Field, BC, on 5 June 1916. This building follows the standard plan which can be found in the online CPHA documents library. Photo courtesy Canadian Pacific archives A.2320.

Conclusion

In the dying days of Revelstoke’s icehouse in 1970, the icing crew (no sweet job, that) was called to service two private cars on the tail of hotshot no. 902. One was business car #19 assigned to divisional superintendent Fred Booth, a man with a reputation as “last of the hard-boiled supers”. Three young guys were tasked with replenishing the rooftop coolers via a ladder. Calculating to save effort, their de facto leader figured he could stand at the roof trapdoor and catch pieces of ice thrown up by his strong-arm companions, who were working out of sight of the elite passengers.

Today, the only remaining icehouse I know is at Banff station, where a small disused building has been saved for a future railway heritage village.

The first pitch up made it all seem good. But the next was slippery, and the catcher fumbled. The chunk went right over the coach and fell to the asphalt beyond, missing two passengers by just feet, bursting into ice cubes. The goof on the roof felt a chill. The startled faces staring back included his ultimate boss Booth, and Pierre Berton. Berton was travelling as a esteemed company guest, filming his upcoming TV series, The National Dream. I expect Booth’s evil eye must have felt like The Last Spike being driven into a career's coffin.

These were end days of railway icing across the continent. CP discontinued its service by 1973. Other railways simultaneously ended their reefer business, including Pacific Fruit Express (reporting mark PFE), an American refrigerator car leasing company. Today, the only remaining icehouse I know is at Banff station, where a small disused building has been saved for a future railway heritage village. Rail author Terry Gainer writes of his experiences with it in his 2019 memoir When Trains Ruled the Rockies. As with this author, he recalls those bygones with fondness.

Those were the days my friend

We thought they'd never end

We'd sing and dance forever and a day

We'd live the life we choose

We'd fight and never lose

For we were young and sure to have our way.

– folksong sung by Mary Hopkin, 1968

| ICY WESTERN WATERS | ||

|---|---|---|

| Railway name |

Harvest Water |

Near Location |

| Cdn National | Yellowhead Lake Fraser River backwater Lake Kathlyn |

Lucerne, BC McBride, BC Smithers, BC |

| Cdn Pacific | Klahater Lake South Thompson River Griffin & Three Valley Lakes Bow River Bow River Lake Minnewanka Crowsnest Lake |

Emory, BC Kamloops, BC Revelstoke, BC Banff, AB Keith, AB Banff, AB Crowsnest Pass, AB |

| Great Northern | Otter Lake Mirror Lake |

Tulameen, BC Kaslo, BC |

| Kettle Valley (CP) | Osprey Lake | Penticton, BC |

| Pacific Great East’n | Kelly Lake | Clinton, BC |

Ice harvesters were not always railway employees, but contractors who used their own men. The successful bidder needed ready access to horse teams and sleighs. At its peak about 1947, the CPR alone was using 300,000 tons per year.

Acknowledgements

David Davies for his assembly and donation of reference materials about railway ice to the Northern BC Archives. UNBC Archivist Kim Stathers for patience and helpfulness replying to my frequent emails. Hal Stathers (now deceased) for sharing his own writing about PGE ice houses. David Meridew for his transcription and donation of the historic newspapers quoted here.

Further reading

- Bowen, H B, ‘Air Conditioned Passenger Cars’ in Factors in Railway and Steamship Operation, Canadian Pacific Railway Foundation Library, 1937, pages 130-135.

- Canadian Car & Foundry Co. Ltd., ‘Express Refrigerator Cars: Built Complete for the CPR’, Bulletin no. P.5, October 1922. Contains a plan and a photo.

- Inghram, J W, ‘The Operation of Car Icing Stations’ in Railway Age, vol. 75, issue 26, December 1923, pages 1214-1215.

- Lambert, David, ‘Ice and the railroads: Pt. III—railroad icehouses’ in Railroad Model Craftsman, June 2012, pages 68-76.

- Whippany Railway Museum, ‘URTX Ventilated Refrigerator Car #50056’, [online] Available at: https://whippanyrailwaymuseum.net/equipment/urtx-ventilated-refrigerator-car-50056/ [Accessed 17 July 2024].

Did You Enjoy This Article?

Sign Up for More!

“The Parkin Lot” is an email newsletter that I publish occasionally for like-minded readers, fellow photographers and writers, amateur historians, publishers, and railfans. If you enjoyed this article, you’ll enjoy The Parkin Lot.

I’d love to have you on board – click below to sign up!