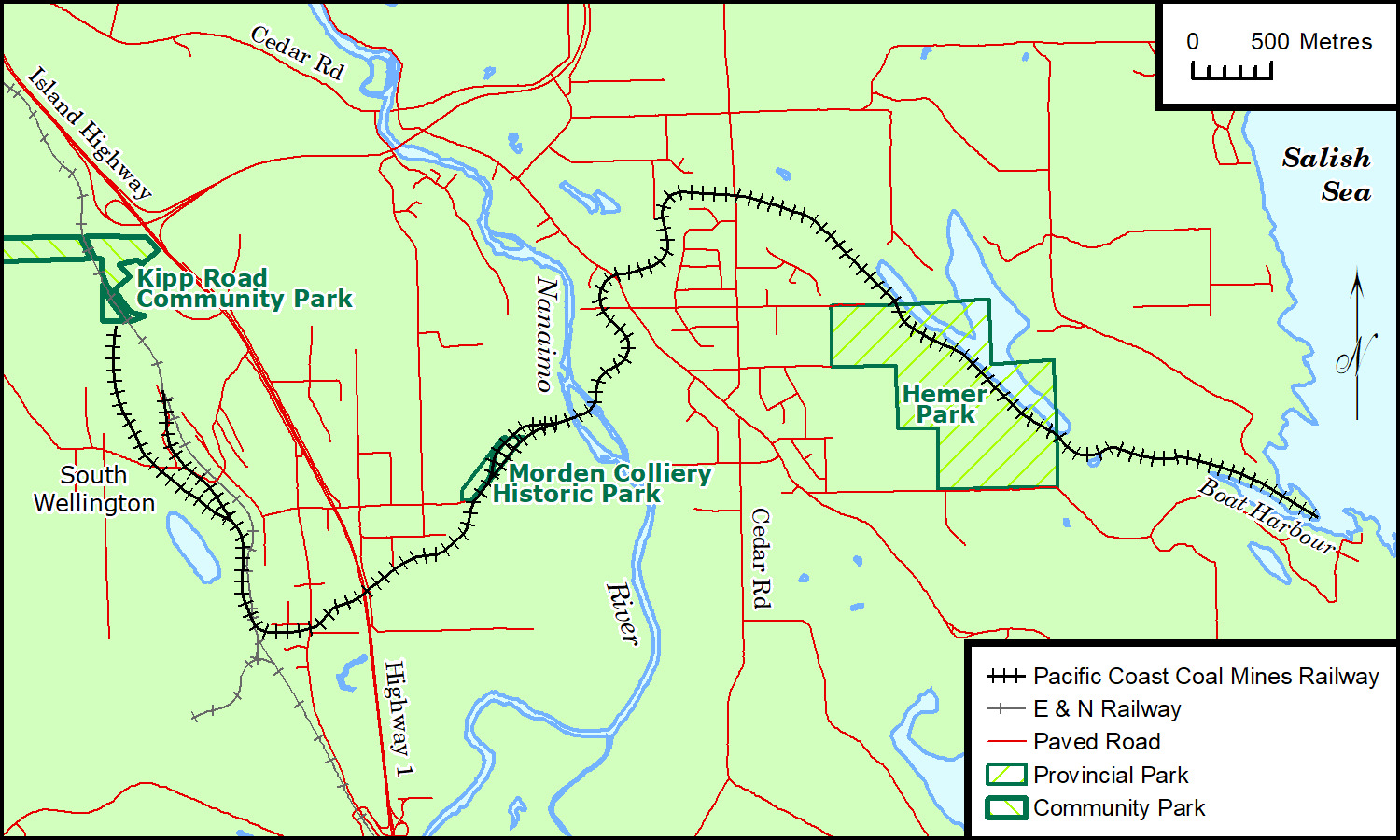

Black Track BC’s Pacific Coast Coal Mine Railway

You can still walk its track today, along the old cinder and coal-dust railbed. The rails are gone, but here lies a lump of bituminous coal, and there, a buried track bolt and spike—reminders of the Pacific Coast Coal Mine’s shortline south of Nanaimo on Vancouver Island.

Short indeed: at its peak, the PCCM line spanned just 11 miles (17 kilometres), including 3.25 miles (5.2 km) of sidings. Despite its size, the company attracted investors from England and the Americas and had a significant local impact through payrolls and regional development. Yet it was modest compared to other, longer-lived coal companies on the Island.

The rails are gone, but here lies a lump of bituminous coal, and there, a buried track bolt and spike...

Coal mining here began with the Hudson’s Bay Company, which was introduced to the seams by Coal Tyee, a chief of the Snuneymuxw First Nation, in 1852. Though the HBC quickly capitalised on the find, they lacked mining expertise and sold their operation to British interests in 1862. Then came Robert Dunsmuir, who started his mine in 1869 and amassed a huge fortune—and even a castle—within 19 years.

Dunsmuir, the province’s wealthiest man, also wielded political power. He founded the Esquimalt & Nanaimo Railway, completing it a year after the Canadian Pacific Railway finished its transcontinental line in 1885. Sir John A Macdonald attended the final spike ceremony. The E&N, a natural fit for Dunsmuir’s mining empire, extended up-Island before his family sold it to the CPR in 1905. Though ownership has changed over time, locals still call it “the E&N.”

South Wellington

The development of competing mines in South Wellington was initially hampered by Dunsmuir’s dominance over the coal industry and his notorious readiness to confront anyone who threatened his wealth—even members of his own family. A vivid example is the legal battle between Dunsmuir and his son-in-law, Henry Croft, referenced in my article on Croft’s Lenora, Mount Sicker Railway.

Despite these challenges, other mining ventures eventually found opportunities to carve out their own operations. Among them was a consortium of wealthy investors who, in 1908, raised three million dollars to support their ambitious plans.

They amalgamated two family-run mines in the South Wellington area, located five crow-miles south of Nanaimo. This merger gave rise to Pacific Coast Coal Mines, Ltd. (PCCM), a company that initially appeared to embrace a more modern, progressive approach than the Dunsmuir oligarchy.

View of Beck Lake from the slack pile of No. 10 mine, South Wellington. The highest point of trees in view grow on the manmade hill of slack pile from the No. 5 mine. Compare this contemporary photograph with a view of the same hill, taken 30 years earlier (see next photo). Photo © TW Parkin.

On 21 February 1974, a broken rail overturned southbound Train No. 52 at South Wellington at a point which allows closer view of a slack pile (see previous photo), as well as the disused right-of-way of the PCCM railway across the field immediately below. The embankment was later removed to allow for agricultural use of the underlying soil. Photo © Ken Perry.

PCCM operated two mines with inclined shafts, known simply as No. 1 and No. 2. Coal was extracted and transported upward via carts linked to a towrope. These shafts descended at a 15-degree angle, following the eastward-sloping “Douglas seam” deep underground. The mines were located just beyond the Esquimalt & Nanaimo Railway (E&N) right-of-way but so close that their ceilings required timber reinforcement to prevent rockfalls caused by the vibrations of passing locomotives.

The mines were located just beyond the Esquimalt & Nanaimo Railway (E&N) right-of-way but so close that their ceilings required timber reinforcement...

Local hobbyist Ron Mayovsky has turned his fascination with this history into a unique pursuit. For the past seven years, he has salvaged discarded iron components from abandoned mining carts in the area. Back at his workshop, he refurbishes the metal, mills new wood, and reconstructs the carts with remarkable authenticity.

On his property, he has even created a small rail yard featuring tracks in both 30-inch and 36-inch gauges, where he demonstrates the various cart designs used for manual and semi-automatic dumping.

Coal mine carts restored by Ron Mayovsky of Cedar, BC. These vary in design, depending on the mine where they were used. Some allowed cartage of both men and mineral. Mayovsky has done this on his own initiative, but was also involved in restoration of a full-size, standard-gauge coal hopper for public display elsewhere (see next photo). Photo © TW Parkin.

This coal hopper was reconstructed using original parts from a 1905 Union Collieries railway. Original blueprints were used to ensure accurate reconstruction. Custom-milled Douglas-fir timbers were constructed by Ron Mayovsky. The car was built off-site and then brought to a former mine in nearby Extension, BC, to be joined to the original trucks. Photo © TW Parkin.

At the South Wellington site, a single tipple served both mines. This raised industrial structure was where coal was offloaded from underground carts, washed, sorted by size, and loaded into railway hoppers. PCCM’s operations stood out from others in the region because they bagged their coal for distribution. A nearby steam plant powered the mine’s ventilating fans, dewatering pumps, winches, and the tipple’s sorting screens.

A weathered concrete arch in an overgrown field marks the tipple’s former location...

Today, little remains of these once-bustling facilities. A weathered concrete arch in an overgrown field marks the tipple’s former location, while the moss-covered foundations of boilers and engines lie hidden in the surrounding forest.

Initially, PCCM used an E&N spur to transport its coal, but for reasons unknown, the company soon opted to construct its own railway. By 1910, a standard-gauge line stretching 7.75 miles (12.7 km) connected the mines to a new dock at Boat Harbour on the Salish Sea. Much of the railway’s route remains accessible today, and I encourage readers to explore it. The trail is currently undergoing development and interpretation by regional authorities.

PCCM tipple at South Wellington. The facility closed in 1917 and was demolished, leaving only its concrete foundation, not visible here.

This concrete arch is the most obvious remaining part of the PCCM mine. It is believed to be part of the former tipple, and possibly supported a mechanical shaker for sorting coal by size. The exfoliated concrete reveals it was reinforced with sections of underground track rail. Photo © TW Parkin.

Unfortunately, PCCM never achieved the success its investors had envisioned. Internal disputes led to litigation, and by December 1912, new management had taken control. These upheavals trickled down to operations at the mine level, resulting in oversights.

The resulting flood drowned 19 PCCM miners in the dark.

One such lapse culminated in disaster on 9 February 1915, when a detonation inadvertently breached an abandoned neighbouring mine filled with water. The resulting flood drowned 19 PCCM miners in the dark. Legal battles ensued, further destabilising the company. Investigations also revealed that shares had been reserved for political favours, adding to the company’s troubles.

Despite these setbacks, PCCM sought to prolong its operations by planning a new mine three miles (4.8 km) down the railway at Morden Colliery.

Morden Colliery

Morden mine works 1910-20. Showing the hoist house in centre mid-ground, with the concrete headframe and tipple on its right. The wooden headframe, built for ventilation, also served as an emergency hoist. Its hoist house is on the extreme left. In the rear, the water tower and smokestacks of the powerhouse.

To its credit, PCCM started a state-of-the-art operation which included electric lights (no open-flame lamps), coal cars (no mules), and automatic dumping of cars (less work). They were planning for a 50-year operational life. Work started in 1912, but by December, Morden miners went on strike for $4.50 per day. All of 1913 was characterised by violent labour unrest, which rattled every coal community on the Island.

All of 1913 was characterised by violent labour unrest...

A good part of the town of South Wellington was torched, and the militia was ordered in to protect corporate properties and scab workers. PCCM spent 1913 preparing for the return of its miners. It built a concrete headframe at Morden, laid heavier rail, shopped for a new locomotive, and generally prepped for the future.

They were reaching once more for the Douglas seam, now 600 ft (183 m) below the surface. The shortest way to it was by blasting a vertical shaft, which they duly built in the style of the time, only with a headframe of reinforced concrete instead of timber. It was the first such design on the Island and, today, is only one of two such tipples in North America.

The structure was recognised as a Canadian National Historic Site in 1971. As author and historian Lynn Bowen wrote, “It is ironic that the Morden mine [became representative] even though it, of all locations, is the least representative of Vancouver Island coal mines.”

Morden headframe. The winding cables can be discerned, sloping back to the winch house on the left. A steep staircase on the left strut is ‘made safe’ by a railing. Compare with colour photos of the same structure today. This image taken circa 1920. BC Archives photo I-68012.

Built in 1912 for the Morden mine site, this tipple was used to hoist and sort coal for loading into rail cars below the bunkers. It was the first (and now last) of its kind in Canada, and one of the earliest built in North America. Photo © TW Parkin.

Much of the industry was built with wood, so what with fires, moved buildings, and wet coast weathering, very little now remains. The ruins of this industrial complex do evoke a strong sense of history. Hidden among the trees are remnants of the steam plant and the concrete base of its chimney. The winding house and other facilities can still be identified, and will interest railway modellers. The 22.5-m (74 ft) headframe and tipple dominate the scene. All were located on multi-tracked sidings which allowed by-passage of through trains.

After the flood and strike, PCCM de-watered its South Wellington operations but gave up in 1917, moving 14 family cottages, a boarding house, and an office to better prospects at Morden.

...by the time tunnelling reached truly promising seams, the miners again went on strike.

Time revealed the newer coal deposits as patchy, and by the time tunnelling reached truly promising seams, the miners again went on strike. The company also clashed with local settlers over mineral rights. Though shipments were made, serial issues beset them. One wonders whether their railway crews were fully employed. It seems that track and shop workers were not.

This is suggested by reports from provincial Railway Department inspectors. They oversaw safety for both citizens and employees. Inspector William Rae’s report of 18 January 1916 found issues with bridges, absent crossbucks, and loose rail joints. To its credit, PCCM made upgrades following his complaint. However, when Rae returned in September, he noted Loco #3 had badly worn flanges and tyres inflicted by twisting, uneven grades.

The next year Rae wrote: “With reference to the cars, I have noticed several in a very worn-out condition, especially with respect to the sills. Regarding the general condition of your equipment, I am not at all satisfied and must request that more attention be given same.”

48-ton locomotive #3 awaits her fate, still stored outside in 1929 at Morden mine site. The cab of #2 is visible on the immediate right. Their owners went into voluntary liquidation in 1922. Both engines were sold and scrapped in the Cowichan valley about 1936. BC Archives photo H-06570.

In 1918, the company ripped up its track behind them (between South Wellington and Morden), reducing necessary maintenance to 5.5 mi (8.8 km), mine to seaboard. It appears they were conserving cash for other priorities. Poor performance reports continued until PCCM could no longer postpone action. A flurry of track and engine improvements were made in 1920.

But it was for naught.

The November 1921 issue of the Canadian Mining Journal reported: “The affairs of the Pacific Coast Coal Mines Ltd appear to be in an almost inextricable tangle, both in point of litigation and finances.”

The mine was unable to satisfy payroll and was reported as closed in 1922 with only one watchman on staff. It officially shut down in 1930, leaving large deposits in the ground, but by then coal was no longer king — it was the new empire of oil.

The base of the steam plant chimney at Morden colliery resembles the concrete remnants at the South Wellington tipple. Here, it was of different purpose. It is the foundation of a demolished smoke stack 60 ft (18 m) tall. Photo © TW Parkin.

“Fairy Fingers” (Clavaria fragilis), a fungus, extends its growth up from the ground, resembling the ghostly digits of long-forgotten miners, clawing their way to daylight. The plant is common on the forest floor of North American mixed woodlands. Photo © TW Parkin.

The PCCM railway

The railway connecting South Wellington and Boat Harbour was the lifeline of the PCCM. The route efficiently provided coal to the coast and brought equipment and supplies in to the mine.

For the benefit of historians and hikers, two parts of the old rail route have been protected by regional and provincial park status, which include surface remnants at the old Morden colliery site. At the moment, the rail trail is broken by the Nanaimo River (the PCCM Howe truss bridge having been removed decades ago). However, the Regional District of Nanaimo announced in November 2023 that it has selected a future bridge design which will “accommodate pedestrians, cyclists, equestrians, and those with medical mobility aids.” Spanning the river will be a metal truss bridge worth an estimated $5.2 million.

For fun, this author metal-detected the abutments of the former PCCM bridge and uncovered a drift pin and timber bolts typically used on Howe trusses of the past. Elsewhere along the right-of-way, track spikes, broken joint bolts, and other paraphernalia can be easily found.

| Loco Roster and Rolling Stock | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Road # | Delivered | Builder | Whyte | Outcome |

| No. 1 |

1914 | HK Porter, Inc | 0-4-0 | Stored/sold*§ |

| No. 2 | 1909 (new) |

Montreal Loco Works | 2-4-2 | Stored/sold* |

| No. 3 | 1916 (ex CP) |

Canadian Pacific #328/6032 | 0-6-0 | Stored/sold* |

At maximum, PCCM owned 25, 25-ton hoppers purchased used and 30 wood Hart-Otis side-dumpers (40 ton). From old BC Railway Department annual reports, three seem to have been converted to flatcars. All equipment had air brakes and automatic couplers.

* Each was stored in the period 1921-1929, then sold to the Mayo Brothers Timber Co., which ran a major logging and lumbering operation. They scrapped them all in the 1930s.

§ There is presumed to have been a prior #1, but authors on the subject are contradictory.

The old rail steel was likely harvested by the bankruptcy trustee, but two lengths were left along the trail for some reason. One measures full length at 30 feet. It’s dated 1908, and was milled in Illinois to 50 pounds per yard. We’ll never know whether this steel was bought as new or as relay. Future finds as the trail is upgraded may reveal more.

To follow the rail route entirely from South Wellington is not possible without permission from current landowners, so photographs accompanying this article were obtained legally. At the northerly mine site, informal trails, especially one named ‘Coal Dust’ in Kipp Road Community Park (see AllTrails.com) will take you through public lands which edge the E&N Railway. Here can be found all kinds of debris from former occupants, plus sunken ground where subterranean chambers have collapsed.

I found a bell, still with a bit of leather harness attached to it. About yea round. And that would be from one of the pit ponies. If you look, there were horseshoes coming through the ground. They range from very small, i.e., your pit pony, to your classical Clydesdale. And then ones that are in-between size and are quite elongated; those are mule shoes. So, you can actually learn things by reading the ground.

Long ago, an E&N steam train was derailed by just such a subsidence beneath its roadbed. A vicious rail acting like a ‘snakehead’ of antebellum days tore through a coach floor, but no one was killed.

Enclosures in Kipp Road Community Park protect visitors from areas prone to subterranean collapse. Other subsidences are left unfenced, so keep out of the depressions because they act like ant lion traps. There are plenty of ruins to explore safely nearby. Photo © TW Parkin.

Metal remnants abound on the surface around PCCM Mines No. 1 and No. 2. Bottle diggers and metal detectorists have long disturbed the ground, leaving behind these discarded treasures. Photo © TW Parkin.

In sequence, the next point of interest on the PCCM line is measured at E&N Mile 66.2. Here our line of interest passed under a half-through deck plate girder of the E&N. It was filled in 1966, but the adjacent cut blasted through sandstone bedrock is still obvious. This location can be accessed by vehicle from Kimball Avenue off South Wellington Road.

On the west side of the tracks this backroad takes you onto a huge pile of black waste known as “slack” from No. 10 Mine. From its summit view, an agricultural plain shows another unnatural hill. These are two remnants of coal mines in the greater Nanaimo area. All shafts and adits were dynamited shut for public safety after two exploring boys were lost underground, many, many years ago.

The next place to visit on our PCCM tour is Morden Colliery Historic Park. It’s small; only four hectares (10 acres), and was established in 1972. Here you’ll want to park and walk around the restored tipple and ruins of the invisible ghost town. A 0.8 km (half mile) trail follows one of the old tracks down to the Nanaimo River through a mixed forest lacy with sword ferns. In the fall, spawning salmon may be seen if the river is clear. Until the new bridge opens, this ends this trail segment.

If wanting to walk more of the line, drive around to Cedar Road, and pick up the next trail segment between the Wheatsheaf Pub (an institution since 1926) and COCO Café (for an excellent light lunch).

This view of South Wellington from No. 10 Mine is looking north and in the distance is the slack pile from the No. 5 Mine. The entrance to No. 10 is in the lower middle of the photo and the grade of the E&N is on the right.

South Wellington tipple showing its rail operations. PCCM obviously shipped bulk coal as well as sacked coal. These cars were wood-sided because the sulphuric content of the coal, combined with the wet climate, caused rapid corrosion of steel cars. Engine #3 with its engine house behind. No covered storage was built at Morden colliery.

Cedar to Hemer Park Trail

The trailhead for continuing the PCCM walk is recognizably marked by a minehead display mimicking the frame at Morden. There is interpretive signage here, but little along the next six km (3.7 mile) of trail. The route follows the rail line exactly.

As you enjoy the forest through which the trail passes, consider that, in places, how it looks now isn’t much different than it looked to train crews a century ago. Along the shore of Holden Lake (Hemer Provincial Park), observe carefully to find railway evidence. Hint #1: parallel tree roots; hint #2: black track.

Other off-track trails can be enjoyed in this Douglas-fir park. One, to a smaller marsh, has a viewing platform popular with birdwatchers. Depending on the season, you’ll find trumpeter swans, bald eagles, turkey vultures, or waterfowl. All routes are maintained and provide easy walking.

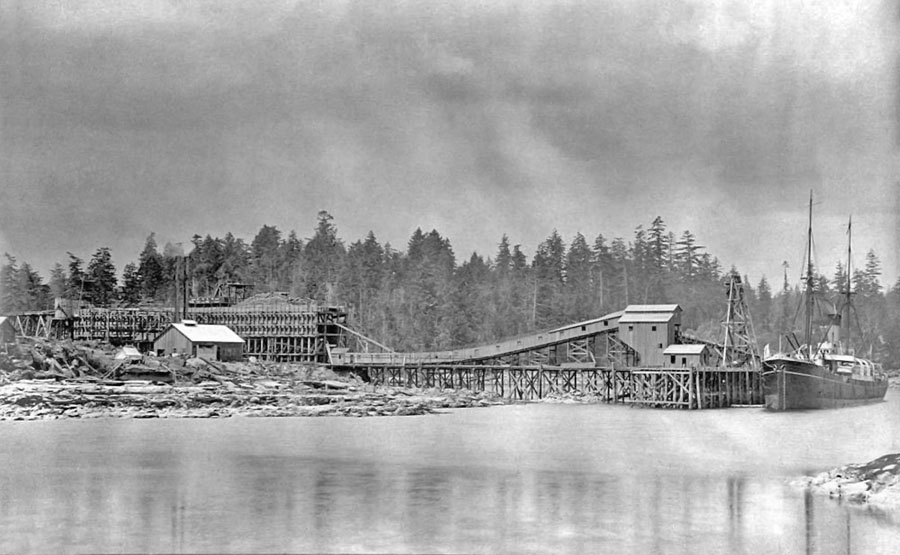

Boat Harbour Dock

Boat Harbour coaling dock in its earliest iteration. Subsequent alterations added to the superstructure. Photographer unknown.

The first shipment of coal from Boat Harbour was in July 1909. Between visiting ships, coal was stored in bunkers holding 5,000 tons apiece. From there, it was loaded onto ships via a rubber conveyor belt one 1 m (3 ft) wide and 228 m (750 ft) long. It could be raised and lowered, as well as swing side-to-side, to accommodate the different ships which called. A washery also operated, using water piped down from Holden Lake.

The ‘black sand’ beaches of Boat Harbour today indicate their industrial past. Landowners in the area are territorial, so the last 1.6 km (mile) of roadbed, and the former dock, are today inaccessible. Very little of the former industrial activity is visible, but an anchor from a marine accident has been retrieved and is on display in Nanaimo’s harbour front plaza.

Author Parkin poses with a hand-forged anchor from one of the largest ships to load coal in Boat Harbour. That ship, the SS Northland, known as a steam packet, was a three-masted sailing ship with a steam engine. While positioning to load coal at bunkers 600 feet from shore, it encountered strong wind. Attempting to slow the ship, the anchor was dropped. It snagged and broke off. The ship eventually ran into the dock. The anchor was found and displayed in downtown Nanaimo in June 1985. Photo © JS Thorne.

Left to right: bunkers (powerhouse to the fore), loading plant, and docks at Boat Harbour in 1909. The sloping shed protects the conveyor belt from the elements. The ship alongside is still loading coal. BC Archives photo I-62138.

Conclusion

The discovery of coal in 1849 resulted in an explosion of mining activity on Vancouver Island. For decades, coal dominated the region’s economy, providing more jobs than any other industry. Nanaimo and many of its neighbouring towns grew out of coal communities, but by the early 1930s, both the PCCM and the hamlet of Morden had been dismantled.

Today, their remains stand as poignant reminders of the coal industry’s historical significance in British Columbia. The remnants of the mine serve as monuments to the labour and ingenuity of a bygone era. The preserved heritage of coal mining continues to be celebrated as a pivotal chapter in the province’s industrial history. These remnants offer insight into the challenges and achievements of a once-thriving industry and its place in Canada's history.

Northward view of No. 1 Mine facilities, South Wellington. Here show the power plant and CPR coal car 39261. The material in the two loaded cars may be slack intended for dumping since at this time, the PCCM mostly marketed its product in sacks, as shown in the stockpile. The E&N mainline passes along the upper right of the photo. From known history, the date 1909 can be deduced. BC Archives photo G-04478.

Same location at photo 22, taken at same time (1909), only viewing southward past the powerhouse. The foremost car is marked PCCM. To the left of the tipple is the elevated narrow-gauge track running into the mine. A considerable stockpile of sacked “nugget” coal awaits empty gondolas for shipping. BC Archives photo E-03775.

Acknowledgements

As with many of my stories, this one is a collaboration. Fellow Islanders and railway enthusiasts have joined me throughout the research, ground truthing, and manuscript phases. In addition to the authors referenced, I acknowledge the contributions and wisdom of Maynard Atkinson, the late John Hoffmeister, Ron Mayovsky, Ken Perry, Chris Sundstrom, and Jim Thorne.

References

Much has been written about coal mines around Nanaimo, and these selected titles are some from which historians have drawn documentation:

- Bowen, Lynn (© 1982) Boss Whistle: The Coal Miners of Vancouver Island Remember, 107 p.

- British Columbia Dept. of Railways, Annual Reports (various), 1918 to 1921.

- Paterson, TW & Basque, G (© 1989) Ghost Towns & Mining Camps of Vancouver Island, 104 p.

- South Wellington Historical Committee (© 2010) South Wellington: Stories from the Past, 1880s-1950s, 406 p.

Did You Enjoy This Article?

Sign Up for More!

“The Parkin Lot” is an email newsletter that I publish occasionally for like-minded readers, fellow photographers and writers, amateur historians, publishers, and railfans. If you enjoyed this article, you’ll enjoy The Parkin Lot.

I’d love to have you on board – click below to sign up!