Ghosts on the Grade

The shattering sound of their exhausts echoing from the sheer rock bluffs and the sight of their billowing plumes of black smoke as the little Shays snaked along the switchbacks, their flanges squealing a protest at the sharpness of the curves on their iron trail must have etched deeply into the memory of those fortunate few who lived in the Westholme valley in that era.

It wasn’t until friend Ralph Beaumont (an earlier Ffestiniog Railway Magazine contributor) arrived here on Vancouver Island, British Columbia, with Omer Lavallée’s Narrow Gauge Railways of Canada that I first trod the railbed of our defunct Lenora, Mount Sicker Railway (LMSR).

Personal memories of its operations are now vaporized like ghosts...

That initial exploration sparked my ongoing interest into a fascinating local line of particular interest to modellers, hikers, and historians. Personal memories of its operations are now vaporized like ghosts, but it’s easy for this enthusiast to imagine the glory days of its activity, so welcome aboard for a short ride into BC’s mining past.

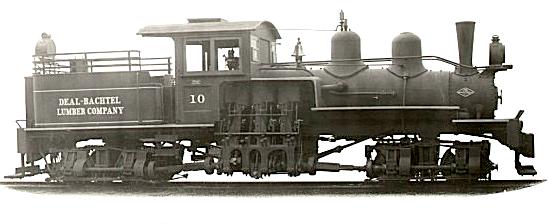

The Lenora, Mt Sicker Railway operated 18.1 km (11.25 mi) between terminals. The crossing over the Esquimalt and Nanaimo Railway is a valley bottom with steep grades on both western and eastern slopes (Mts Sicker and Richards). Map © ME Atkinson.

The LMSR was built to carry copper ore from a mine on a low mountain named Sicker to distant smelters. Prospectors discovered the ore body in 1897, but it took until 1899 for full production to be reached. At that time it lay about halfway between the villages of Chemainus and Duncan, both connected by the Dunsmuir family’s Esquimalt & Nanaimo Railway (E&N).

Coming early to Canada as indentured servants from Scotland, the Dunsmuirs made multiple fortunes in coal mining, but the copper mine came indirectly into their sphere of influence because the man who took up the new mineral deposit married Mary Dunsmuir, a daughter of the family patriarch.

He was England-educated Henry Croft, an experienced project manager and mining engineer.

LMSR tracks through a mature Douglas-fir grove in 1904. Most trees of this size have been logged since, but a sense of this forest is returning today in Eves Provincial Park. Photo by Frank C Swannell, BC Archives #I-33657.

All that is seen may not be real. Spectral Shay #1 reappears from one of her trips of 1901. Original location not recorded. The diamond stack was designed to retain sparks which could create dangerous wildfire. Photoshopping by ME Atkinson.

Croft developed his mine judiciously and stockpiled ore in two categories. Hand-sorted high-grade ore was saved for shipping first because it paid back capital expenditures faster. Keeping investors happy then was a priority, as is true today. The Lenora mine yielded such concentrations that some smelters paid advances—highly desirable for a risky venture.

The first ore down the mountain went by team and wagon which couldn’t keep up with production, even when stronger horses were tried.

The first ore down the mountain went by team and wagon which couldn’t keep up with production, even when stronger horses were tried. Croft’s next idea was a horse-drawn tram on wooden rails. Road builder John Haggarty came north from the capital of Victoria to construct this new route. He connected the mine and its accompanying new town with the E&N near a rural station called Westholme.

The road wound 9.6

kilometres (6 miles) around the forested slopes of Mt Sicker and

included a notorious grade named Haggarty’s Hill. Just how teamsters

controlled their long-suffering horses on its 13% slope may only be

imagined. But their efforts still weren’t sufficient.

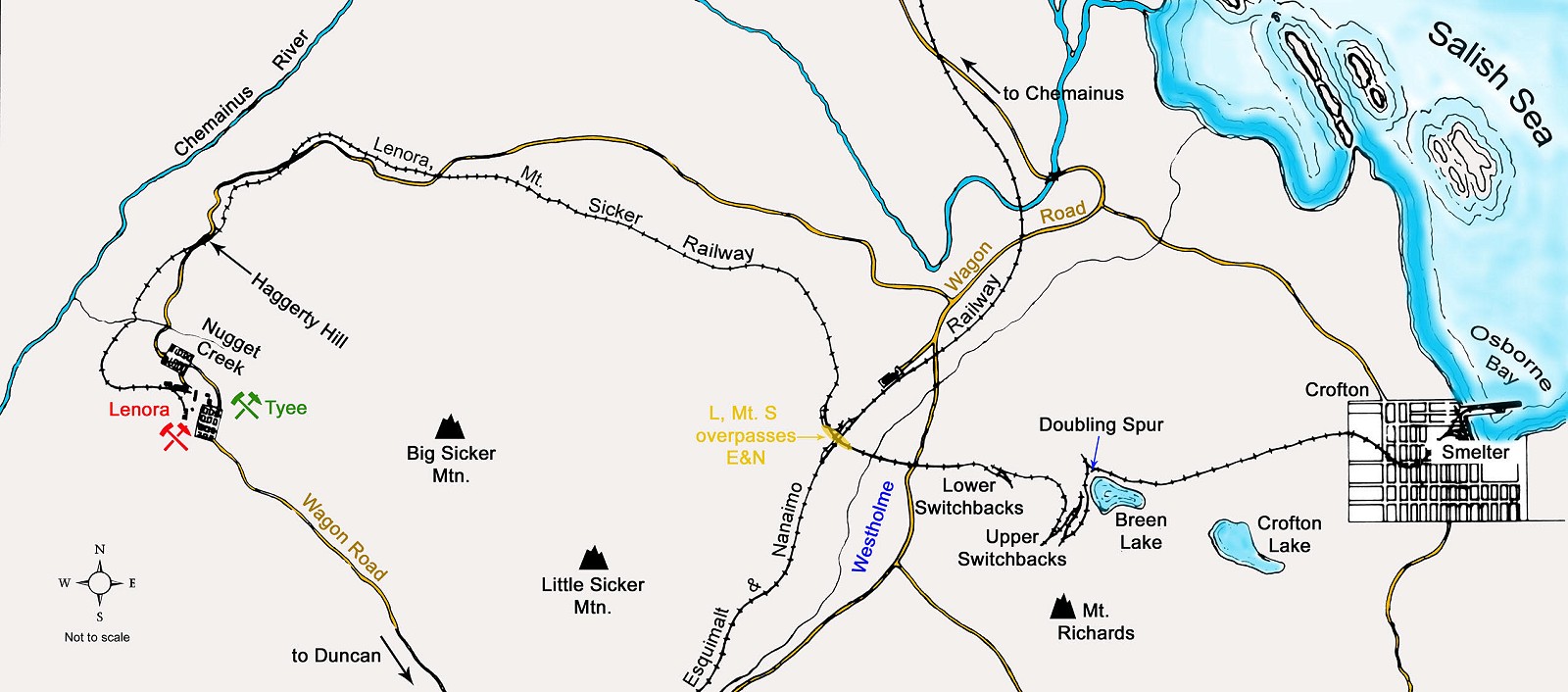

Shay #3 was wrecked about 1906 by negligence. The story goes that ‘a bunch of the boys’ decided to take her to town for ‘supplies’ after the mine had closed and they were thirsty. Things got out of hand and she ditched here, somewhere low on Mt Sicker, and was abandoned. She was sold in 1912 and restored as a logging locomotive. In that line of work she killed two engineers in separate accidents similar to this one. From the collection of Robert Ritchie.

By August 1900 Croft started his next system—a three-foot gauge

railway. A route was surveyed and eight dozen men started construction.

It used much the same alignment as before. At the lower terminus, a raised trestle with a chute allowed dumping of small ore cars into E&N hopper cars. At the mine, ore piled on the ground was disposed of, then the whole site revised for greater efficiency. Soon 60 tons a day were going downhill, so everyone felt relief and optimism. The mountain population grew to 1,700 and a sawmill moved up from the valley.

Soon 60 tons a day were going downhill, so everyone felt relief and optimism.

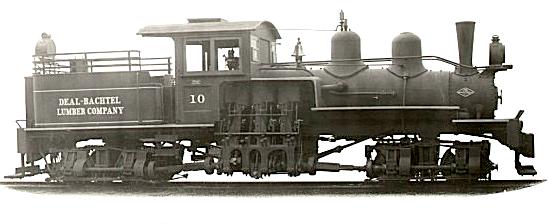

Haggarty’s Hill remained part of the line, so the only engines which could handle its grade were geared Shays.

These mighty engines used steam power, but instead of the usual horizontal pistons and rods driving the wheels, they employed vertical pistons. These pistons rotated a crankshaft, which then transferred power through a system of gears to the small driving wheels. This geared design provided exceptional power and traction, ideal for the LMSR’s steep gradients and sharp curves.

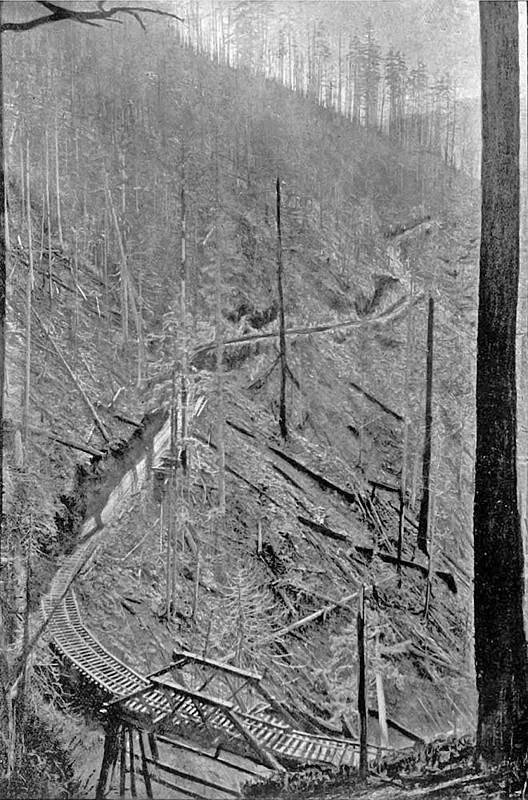

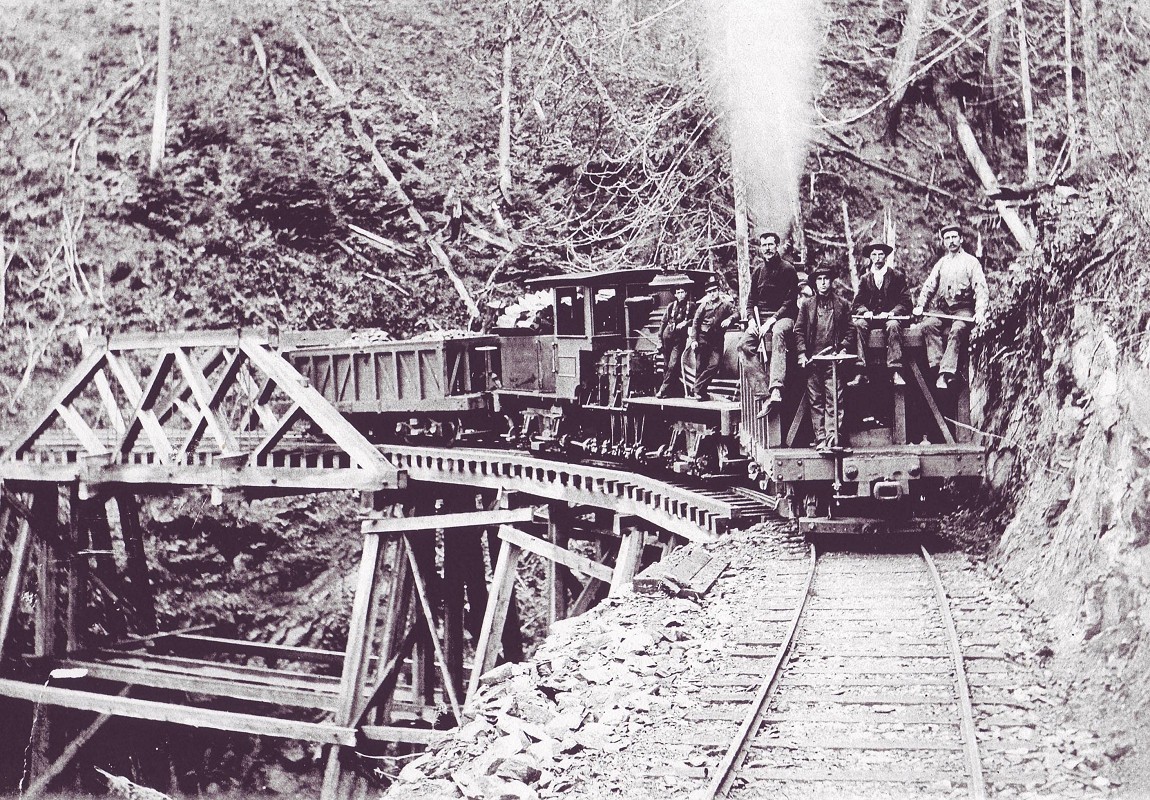

Hair-raising Haggarty’s Hill with the Nugget Creek U-bend over the gully. This whole mountainside was burned in 1896, exposing bedrock which revealed minerals discovered the year following. Photographer unknown, BC Archives #C-08620.

Shay #2 pauses on Nugget Creek bridge. She is backing down Haggarty’s Hill with two cars of ore. Engineer Tommy Grant is nearest the cab, Bill Holman at the brake wheel. His companions hold clubs used for twisting the wheels tighter. Note the link and pin coupler. Photo from the collection of the late Elwood White.

LMSR’s first locomotive was two-cylinder #1 which could pull two five-ton cars—as much as she weighed herself. Operations began to hum, although any ‘passengers’ were compelled to sit on the edge of loaded cars, legs dangling. A news reporter from Victoria’s Daily Colonist wrote of his sudden comprehension of what 50 degrees of curvature meant. Plus watching as an occasional chunk of ore rolled off beside him, followed by his eye into a chasm! I confirm the loss of such payload in that today, metal detecting can become tiresome from the frequent soundings of “hot rocks” (metalliferous ore) along the old railbed.

Two more Shay purchases followed as demand for delivery grew.

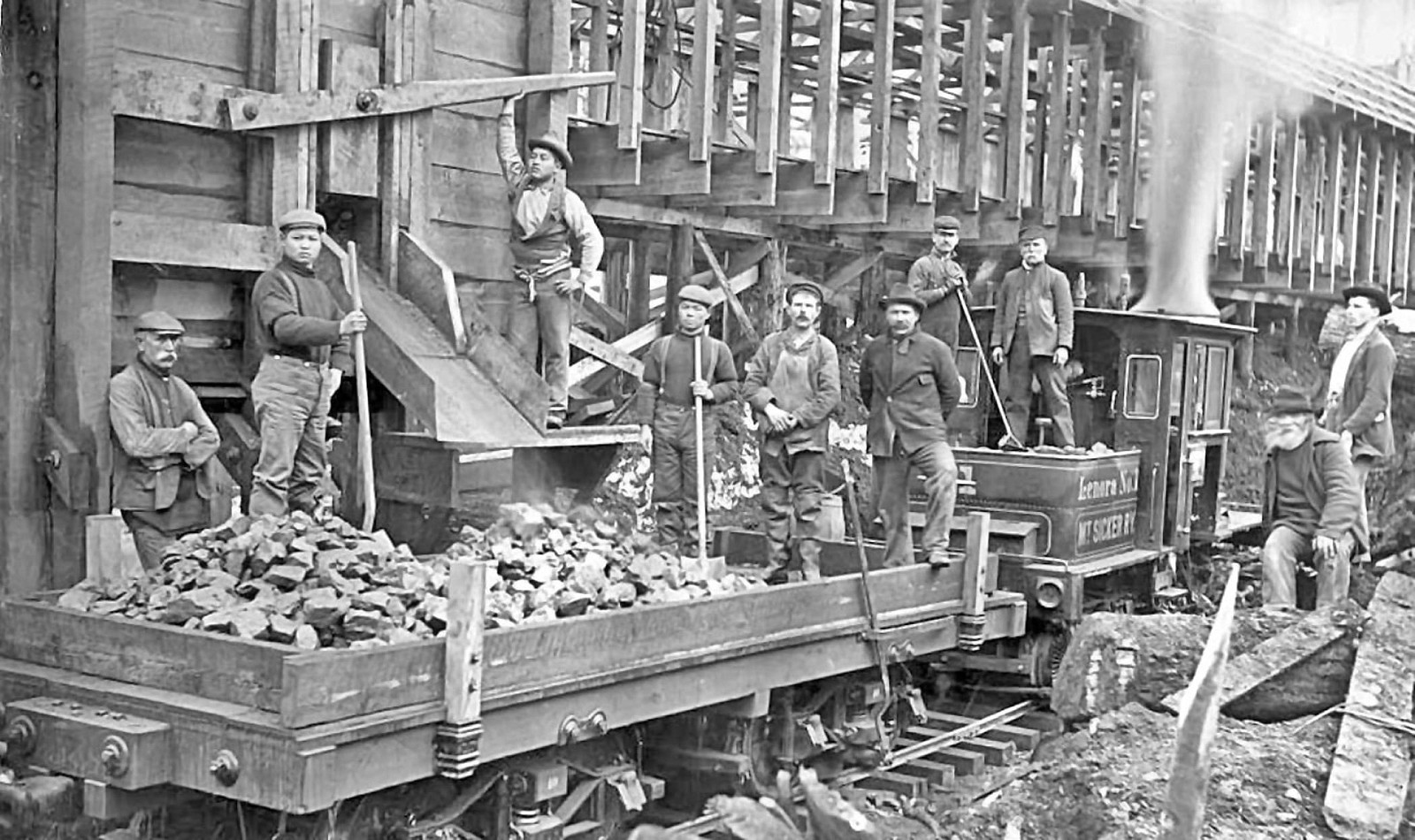

Shay #3 with ore car #5 during construction of the trestle at the Crofton smelter. The track is being bifurcated here into two different bunker buildings. From the collection of Robert Ritchie.

A man working on the Mt Sicker railway the other day fell off a trestle. It was a twenty-five foot fall, but he managed to steer himself into the one spot amid heaps of ties and timber in which his life had a chance. He was laid up only two days.

Henry Croft soon became convinced his brother-in-law was hosing him to haul Lenora's ore. Which is entirely possible, given the reputations of his rapacious relatives.

After arguments and litigation, Henry went all-in. He announced he would elevate and extend his own railway over the E&N to tidewater and build a port there (including a copper smelter), plus a new town to be named after himself: Crofton. This despite construction of another smelter already started in nearby Ladysmith.

But shipping there meant negotiating with the Dunsmuirs. Nothing for it then, but to double the length of his own railway. Except—Mount Richards was in the way. This extension would have to gain 160 metres in altitude over an average 6-7% grade. Not bad, considering he had already contended with 13%.

But this route concentrated nearly all of its steepness on one mountainside . . . the sort of slope for which funicular railways are built.

Here’s how he did it.

An apparition of Shay #3 returns to the mine, pushing empties over the retaining walls on the slopes of Mt Richards. Photoshopping by ME Atkinson.

Croft was under financial strain, so quick completion was his priority. In terms of getting best use out of equipment, since he already used Shays on Mt Sicker, maybe his Richards route seemed to be no particular bother.

Only thing was, the grade limited the new locomotives to just two loaded cars on the uphill, so his ‘shortcut’ was slow. The other consideration is that maximum safe speed for these particular machines was 10-14 mi/hour. The line soon commenced its drama with two short switchbacks. Then it climbed moderately across sunny bedrock exposure.

The railbed here is supported by retaining walls of blasted rubble. These walls are drystone, meaning their rocks are hand-placed, but not mortared together. Their strength comes from friction fitting. This work has been repeatedly described as masterful, but that description originated from newspaper hyperbole.

As a retired stonemason with

drystone training in Ireland, I can reliably inform readers that the

workmanship here is amateurish and it’s a wonder these walls have

remained stable. The builders were simply making use of material on

hand. A few hundred metres further along are exposures of bedrock with

pieces rectangular in natural fracture, and which makes a more desirable

building unit. The contractors didn’t use this because they were

already past places where it could be used and were rushing toward

conclusion.

On entering a coniferous forest higher up, the LMSR commences a set of three zigzags. Curves are not possible, so switchback tails ran out for at least the length of a train. Most seem about 30 meters (≈ 100 feet) long, but one, forced across a gully on a trestle, ran out of room and required excavation into an opposing slope.

The mainline emerged at

the top onto a level area next to what is locally called Breen Lake.

This reservoir and Crofton Lake just downslope were later dammed to

secure water supply for the town and its industry. A doubling spur was

provided here on level ground. This track feature included a separate

leg, just long enough for an extra car or two, for setouts.

Unfortunately, the whole layout has been flooded and not a shadow of track can be seen beneath the lily pads. From here down 4.2 km (2.6 mi) to the Salish Sea, the route is hard to find except by metal-detecting which reveals leftover iron and lost hand tools.

Western Segment (built 1900)

Lenora Mine to Westholme (9.6 km; 6 mi)

But the camp is not yet reached and the train continues its toilsome journey till, when the very summit of the mountain is attained, she swings abruptly into a natural cup-like depression in the hill, where nestling under the Lenora and Tyee mines, a busy little town, proclaims by screaming whistle and singing saw its existence and its enterprise.

Loading at Lenora mine’s ore storage bunkers, circa 1901. This is one of two flatcars adapted for five-ton loads. Note the hand-levered brake, similar in design to that of horse-drawn wagons. Shay #1 waits while a crew of everybody nearby gets in the photo. William Buxton, far left; Albert Holman, far right; Henry Copley sits next to him. RL Gibbs on the ore car with hands folded. Engineer Aaron Garland stands on the tender. Three unidentified fellows nearest the chute are Chinese. Photographer unknown, BC Archives #I-62117.

The ghost town of Mt Sicker is cradled below the summits of Big Sicker Mountain (716 m; 2,349 ft), and Little Sicker Mountain (660 m; 2,170 ft). There was barely room for three spurs of LMSR operations. Another mine, the Tyee, just uphill, was inexplicably forced to find their own way to take ore to the E&N. Such boneheaded competition was to later oblige both mines to close before either of their ore bodies were exhausted.

At valley bottom, the rail route was bisected by the Trans-Canada Highway in the early 1950s, just before reaching the E&N at mileage 46.2, where there was a siding with ore bunkers for transfer to wood hopper cars. Not a sliver of it is left.

Eastern Segment (built 1901)

Westholme to Crofton (8.5 km; 5.25 mi)

The undisputed highlight of this spectacular grade are the switchbacks necessary to overcome it. They are located on the slope of Mt Richards (364 m; 1,195 ft) and partially within a forest managed by the local municipality.

That agency holds outdoor recreation among its mandates, but isn’t interested in alienating the railbed in preference to the value of the timber through which it passes. Consequently, railfans wanting to visit the switchbacks will find no signage and will need a cell phone plus map or excellent detective skills to locate the original route among a snarl of overgrown logging roads.

[R]ailfans wanting to visit the switchbacks will find no signage...

On the west side of Mount Richards, parcels of private property restrict access to the railbed. However, a short section of the route is preserved in Eves Provincial Park. Here it reaches a temporary level before rising again over three tiers of switchbacks to gain a gap in the ridge above.

Within the park the route is a defined trail which climbs along a gully through a beautiful old-growth forest. At one point the trail encounters a 10-m section of badly-rusted track of relaid rail . . . so rotten one can poke a finger through holes in the web. We know the original rails weighed 20 and 28 pounds/yard. The author’s metal detecting hasn’t turned up any rails known to be original to the line.

Tom explains the Mt Sicker rail grade on Mt Richards. (36 seconds). Video © Larry Pynn (sixmountains.ca).

Metal Detecting

Shays on the Switchbacks authors report LMSR rails as coming from the Rhymney Iron Company Ltd. of Wales. Rhymney produced both iron and steel rails for the world, but ceased production in 1891, so long before LMSR placed an order. Thus the rails purchased by Croft were relay rails whose original owner(s) would likely have been in the Pacific Northwest.

Two surviving rails are installed as demonstration track in Eves Park are too corroded to determine any branding on the web.

Found in the forest. Detectorist Tom shows a fishplate, or joint bar, one of a pair of side-braces which once would have bolted two rails together, butt to butt, to make a continuous track. Photo © Larry Pynn.

The variety of discarded fishplates (joint bars), track bolts, and rail spikes found by this author suggest much of such hardware was purchased aftermarket. Not only would it have been cheaper to do so, it would have been quick to obtain because it was probably close at hand.

While my ‘random sampling’ is in no way statistically valid, it suggests the line was assembled on a limited budget.

For example, five different spike lengths have been found here, where there was no other railway. Explanation for this could be that Croft’s agents were purchasing fastenings offered by other industrial lines, but none had sufficient supply to meet his total need.

Conclusion

Switchbacks were once common in British Columbia during the heyday of narrow-gauge railroading, especially for logging operations. The LMSR, though lesser-known, deserves equal recognition for its engineering feats and colourful history. Enthusiasts may need to dig deeper to fully appreciate it, but the effort is rewarding.

Sadly, Henry Croft’s enterprise ended in failure, forced into receivership and closure. By 1912, the rails were lifted, cars burned for scrap, and locomotives sold. Yet, as we tread the path of the Lenora, Mount Sicker Railway, we can still glimpse faint echoes of its past in the landscape and our imagination.

Further Reading

- Muralt, D. and White, E. (July/August 1984) ‘The Lenora Mount Sicker Railway’ Narrow Gauge and Shortline Gazette, Bucklin, Missouri.

- Robinson, J. (November/December 1979) ‘Ore car, Lenora, Mt Sicker Railway’ (drawing only). Narrow Gauge and Shortline Gazette, Bucklin, Missouri.

- White, E. and Wilkie, D. (1963) Shays on the Switchbacks: A History of the Narrow Gauge Lenora, Mt. Sicker Railway. British Columbia Railway Historical Assn, Victoria, BC.

Did You Enjoy This Article?

Sign Up for More!

“The Parkin Lot” is an email newsletter that I publish occasionally for like-minded readers, fellow photographers and writers, amateur historians, publishers, and railfans. If you enjoyed this article, you’ll enjoy The Parkin Lot.

I’d love to have you on board – click below to sign up!