One More River to Cross Revelstoke’s Railway Bridges

Down her wild mountains and canyons she flew

Canadian Northwest to the oceans so blue

Roll on Columbia, roll on.

Charting the Columbia

First Nations, who had travelled the river from time immemorial, knew it well and gave it many names. “Ouragon” was one—today spelled Oregon. In 1775 explorer Bruno de Heceta charted its mouth as “Rio de San Roque.” Spain later lost its claim to the United States, and in May 1792 Captain Robert Gray of Boston entered the river in his ship Columbia and gave it her name. That name endured, but it was North West Company mapmaker David Thompson who first grasped its full length.

...in May 1792 Captain Robert Gray of Boston entered the river in his ship Columbia and gave it her name.

European names accumulated along its course, especially for features noted by voyageurs. One lies on the 51st parallel, which intersects the Columbia twice—creating the famous “Big Bend,” a 180-degree curve that reverses the river between Golden and Revelstoke.

The ’Stoke sits on the bend’s western side beside “the Big Eddy,” a fine backwater campsite for fur brigades. CPR surveyor Walter Moberly even found a blaze left there by Thompson 54 years earlier.

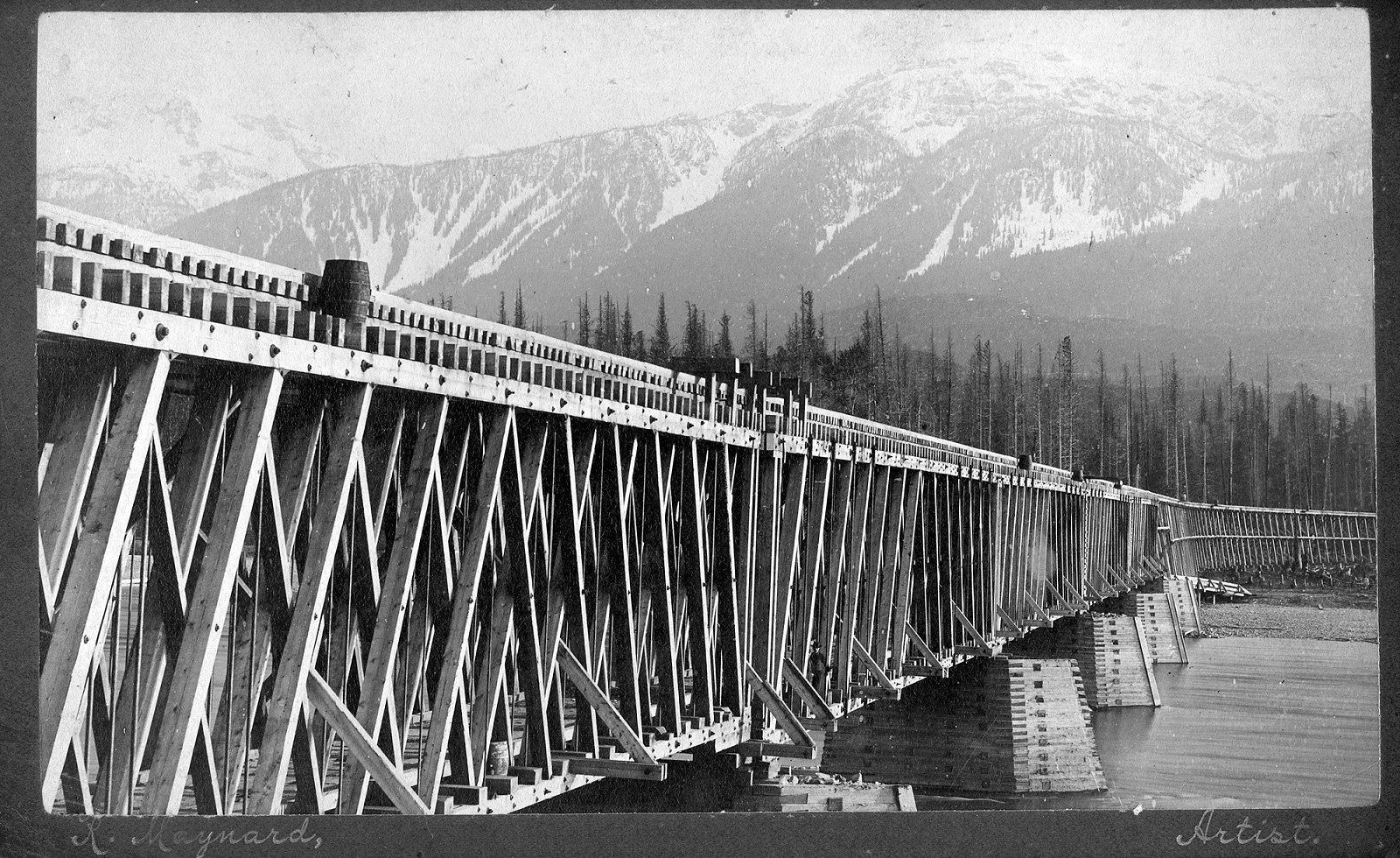

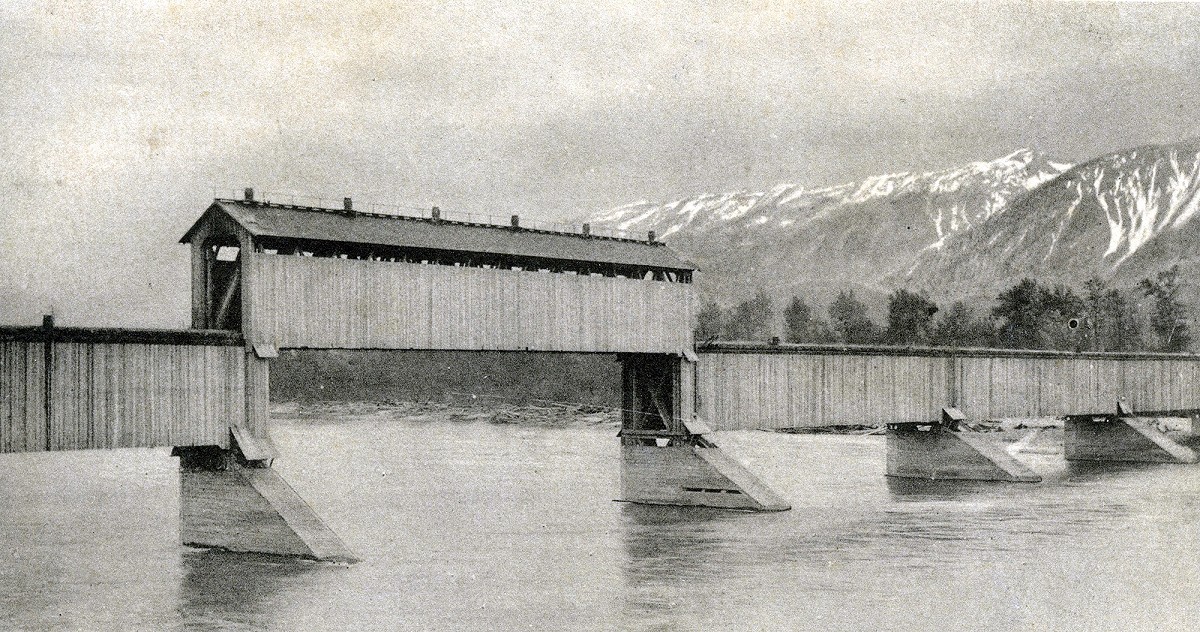

In a crush toward Craigellachie, track crews working toward completion in 1885 put up a trestle which surely gave locomotive engineers knees as wobbly as this structure appears. The functioning bridge is a pile trestle, and could not have survived long in high water season with its accompanying drift of debris. Crib piers for a replacement bridge are already in place, possibly belonging to Gus Wright’s former toll road bridge. This summer 1886 image taken by Oliver B Buell, hired by the CPR out of Montréal. CRHA/Exporail archives A-4237.

Seeking East–West Passages

Moberly was among later surveyors adding more European names to the map—Eagle Pass for instance—as he criss-crossed the region, often on foot, seeking passages running perpendicular to rivers. Southern BC’s mountain chains run roughly north-south, making it easy for Americans still believing in Manifest Destiny to enter Canada via valleys crossing the 49th parallel. They had already done so during the mid-1860s Big Bend gold rush. Sir John A Macdonald was determined to stop that happening again by driving a railway east-west across the intervening mountains.

During the winter of 1884 the CPR’s end-of-steel stopped at Beaver (later Beavermouth) near the Beaver River’s confluence with the Columbia. Coming from east of the Big Bend, tracklayers descended the Rockies to bridge the river there at “First Crossing”.

Next, in the Selkirk Mountains, crews battled deep snow, clearing right-of-way, hauling supplies, and milling crossties and bridge timbers. Not until October 1885 did they emerge from the Illecillewaet valley’s “green dark forest too silent to be real”, (Gordon Lightfoot’s phrase) with 26 miles (42 kilometres) still to go. West of there, contractor Andrew Onderdonk’s crews had run out of rails and telegraph wire the week before, halting progress prematurely in Eagle Pass.

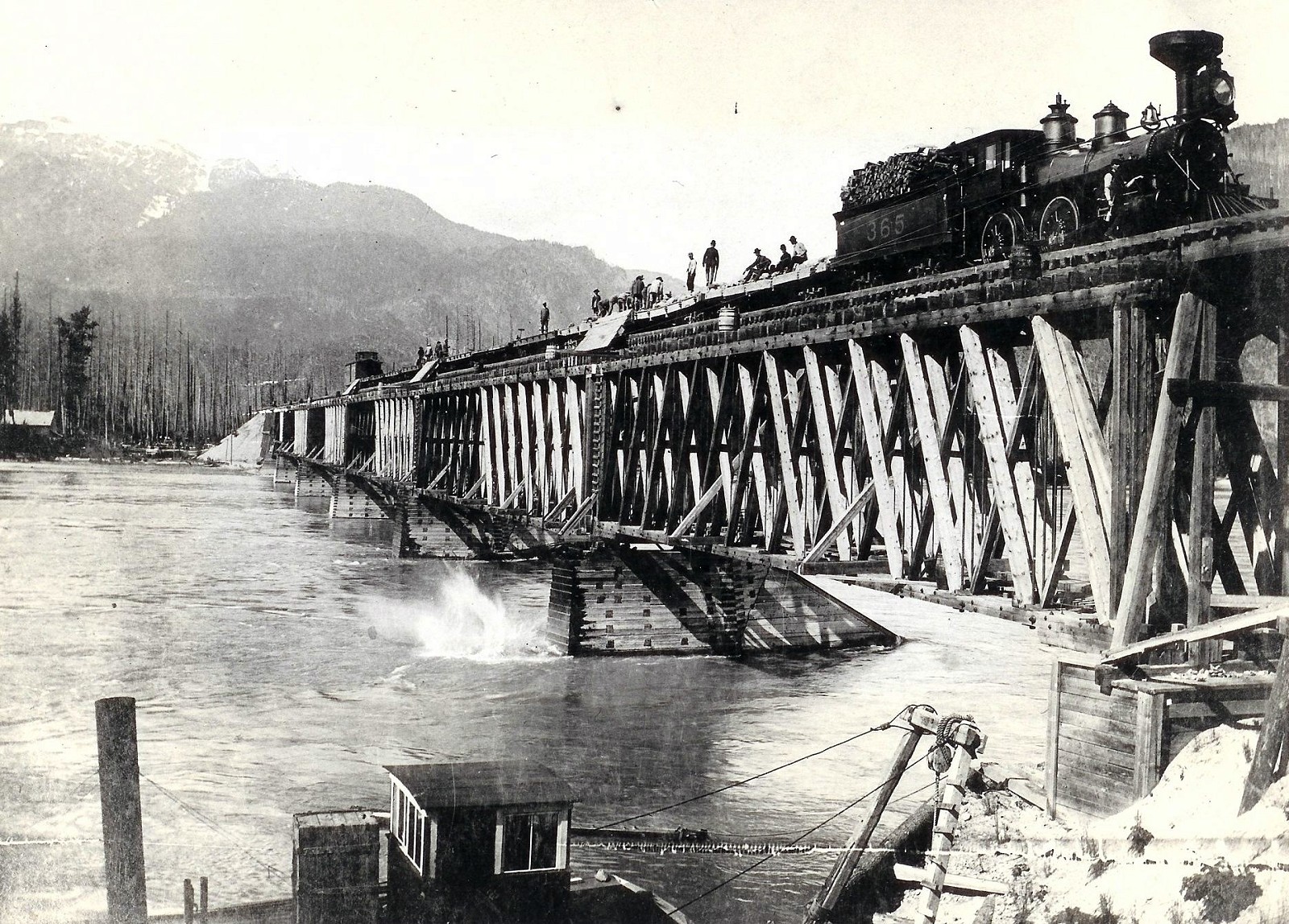

Work train labourers are dropping rock to reinforce the wood piers on the downstream edge. Again, the river is high, indicating concerns about scouring of the riverbed beneath the piers. Ramps have been placed to cast falling stone away from the timbers, thus avoiding further damage. Barrels are positioned for fire prevention, and would have been kept filled by maintenance-of-way services. This bridge design does not allow for vessel passage beneath the lower chord—probably not even the little S.S. Despatch in the foreground. The date suggested is May 1895, as determined by notes in Kamloops’ Inland Sentinel of that time. Trueman & Caple photo, BC Archives B-00553.

Second Crossing at The Eddy

The Illecillewaet (Secwépemc meaning “swift water”) joins the Columbia near The Eddy, aligned with Eagle Pass. Here the CPR prepared a “Second Crossing,” already the site of a private toll bridge built for freight wagons by road contractor Gustavus B Wright, who also owned a sawmill. His bridge aided CPR supply movements and his mill must have provided ties and timbers.

Completion was critical to the company’s—and perhaps the country’s—survival.

A permanent bridge would come later—first priority was to finish the line. This last big trestle carried trains to the section being rushed toward the last spike at Craigellachie. Completion was critical to the company’s—and perhaps the country’s—survival.

On 4 March 1885, project manager Ross told general manager WC Van

Horne: “The West Crossing cribs are completed and filled with stone and I

have a mill on the ground which will be going in a very short time...”

Low winter water had allowed crews to build stone-filled timber cribs on

the ice, easing the work. Yet storms, 30 feet (9 metres) of Selkirk

snow, heavy timbering to descend the Illecillewaet headwall, and a

summer of rain, washouts, and slides upset Ross’s schedule.

...Getting on the bridge, a slight shock was felt, as though the cowcatcher had come into contact with a soft, yielding substance, and the engineer whistled down brakes. As soon as the train could be stopped it was discovered that the obstruction was the body of a man who had evidently been asleep on the track. The body had been carried a considerable distance over the bridge and was disembowelled and otherwise cut up. It proved to be a Finlander named Nicholas Lamp, who had been employed on the CPR as a track-walker ... the poor fellow had been overcome by drink and had lain down on the track to sleep. Death had been instantaneous. No blame was attached to anyone, the driver being a most careful and efficient man.

Birth of the First Revelstoke Bridge

The first Revelstoke bridge had two levels with rails above and road below. It was hastily finished in 1885. It replaced Wright’s toll bridge. By then a townsite had appeared on the east bank, laid out by surveyor Arthur S Farwell, who pre-empted land the railway was obliged to cross.

He expected a divisional point on his acreage and promoted his village as a meeting point of Canadian (rail) and American (river) trade routes. Van Horne was unmoved in his refusal to pay. The CPR founded its own townsite nearby, and in 1886 secured the Post Office name Revelstoke. Farwell eventually became a mere neighbourhood of the larger community.

The first train crossed the Columbia here on 17 October 1885, just 21 days before the last spike at Craigellachie. The mountain portion did not remain open that winter; snowfall was simply too deep. However, crews were kept at work on the second Columbia River bridge, which is presumed finished in 1886.

Strengthening the Second Crossing

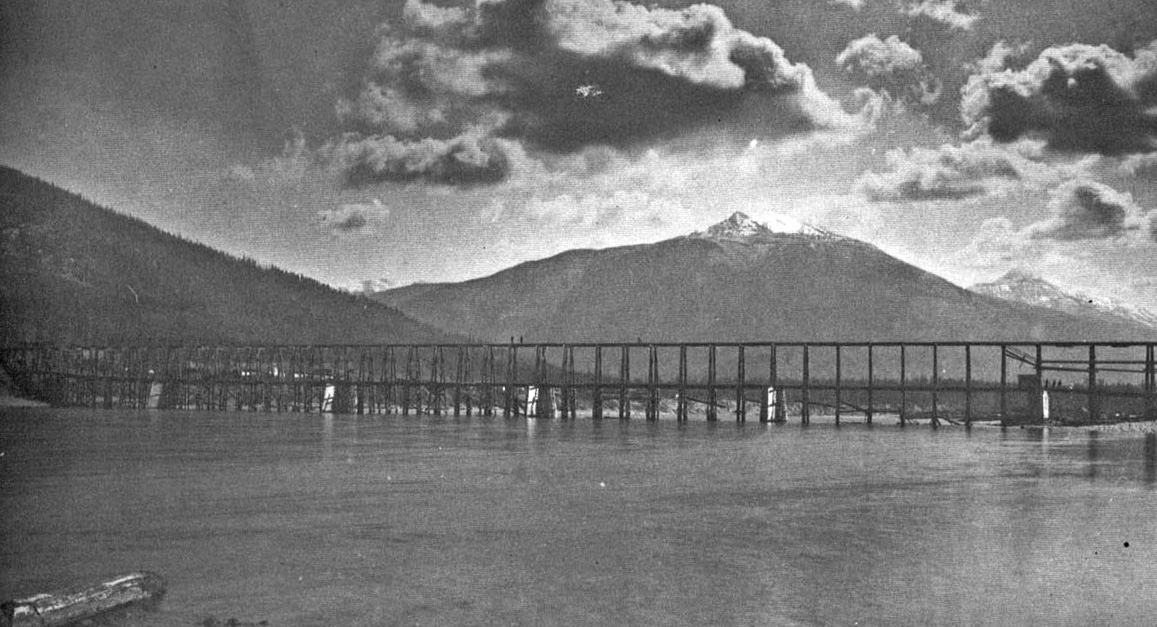

Replacing that initial trestle with a stronger bridge was a major expense. The second bridge, photographed about 1895, shows the river full with spring freshet. One span was raised in the early 1890s. About then, improvements were evidently being considered:

Mr. Griffith, chief engineer of the mountain section of the CPR, was last week engaged in sounding the Columbia River for the foundations of the new railway bridge at Revelstoke, which is to be entirely of iron.

It is said the CPR intends building a new bridge across the Columbia at Revelstoke. The necessary soundings have just been taken.

It is likely that work will start on a new stone and iron bridge on the CPR across the Columbia River at Revelstoke, before the summer is past. Mr R Marpole, superintendent of the division and Mr HJ Cambie, engineer of the division, have gone up to obtain further data with a view of preparing the plans.

Last Monday the Columbia River covered the highest water mark at Revelstoke bridge and five inches beyond. On Tuesday the water fell 15 inches but began to rise again on Wednesday.

The great floods of 1894 had begun. National transportation was shut down for weeks while victims were aided, mudslides cleared, and bridges rebuilt. The repair costs were astronomical. The bridge at Revelstoke held in place due to heroic actions by crews, but the proposed new bridge was set back by years. The whole province was set back by years.

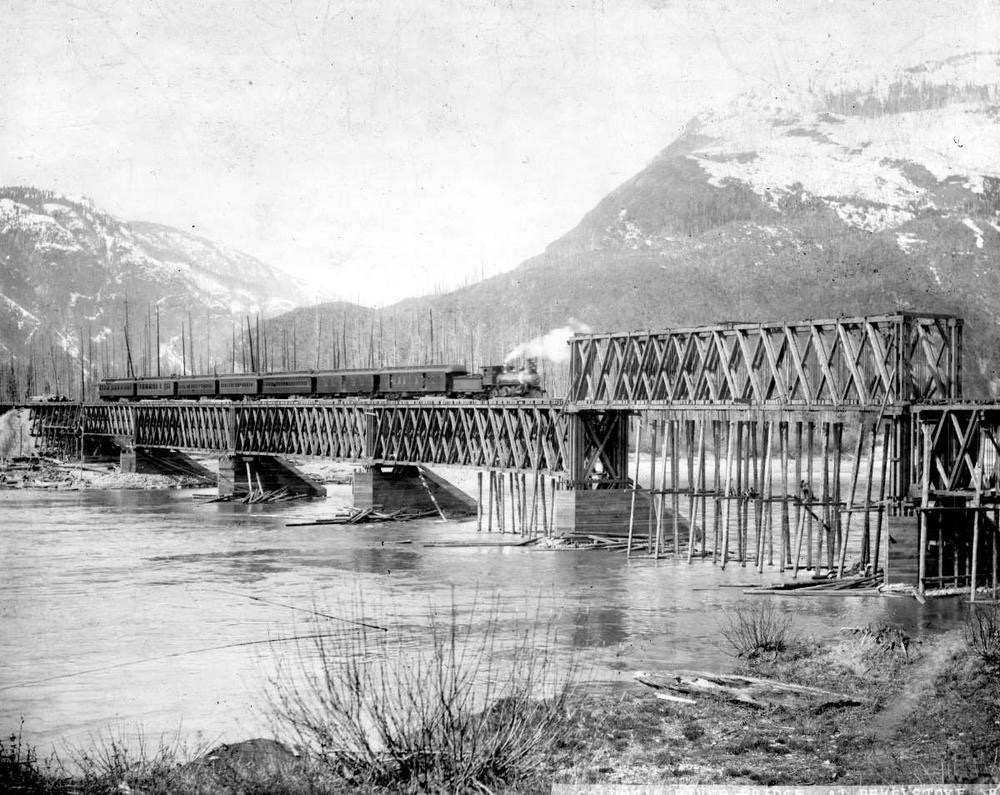

At first glance this picture seems like another knee-knocker structure; a weakened bridge supported by props. But would a respectable railway really run its crack Atlantic Express over such a risk? The month is November (which I can verify, having grown up in Revelstoke) and again low water has been chosen as the best time for such work. So low that loose stone dumped previously to reinforce the piers shows. Three or four men cling to the timber bents under the raised truss, probably disassembling cross-braces which are accumulating below. Note the uprights no longer support the lower chord of the truss; the bridge is now self-supporting, and the bents were probably there for temporary support as the deck truss was raised to become a through-truss. This change allowed steamboats to pass beneath to the benefit of logging camps upstream in Big Bend country. A photo date of August 1895 is assumed, again supported by notes in Kamloops’ Inland Sentinel. BC Archives photo E-00333.

Retiring the Woodwork

Sometime between 1897 and 1907, the timber Howe trusses at Revelstoke were sheathed in planks—probably to protect them from more weathering—12 years is the average durability of wood. This protection prolonged their life but increased fire risk, so water barrels provided protection and watchmen were assigned regular foot patrols.

Covered bridges were rare in BC, with only four having been identified by this author.

Van Horne had paused stone and steel construction back in 1884 to cut costs, but by the late 1890s the CPR was profitable and replacing many wooden spans. Nearby trestles were incrementally replaced with granite and steel by 1899; engineers likely reckoned the Columbia bridge could serve a few more years if kept dry. Covered bridges were rare in BC, with only four having been identified by this author.

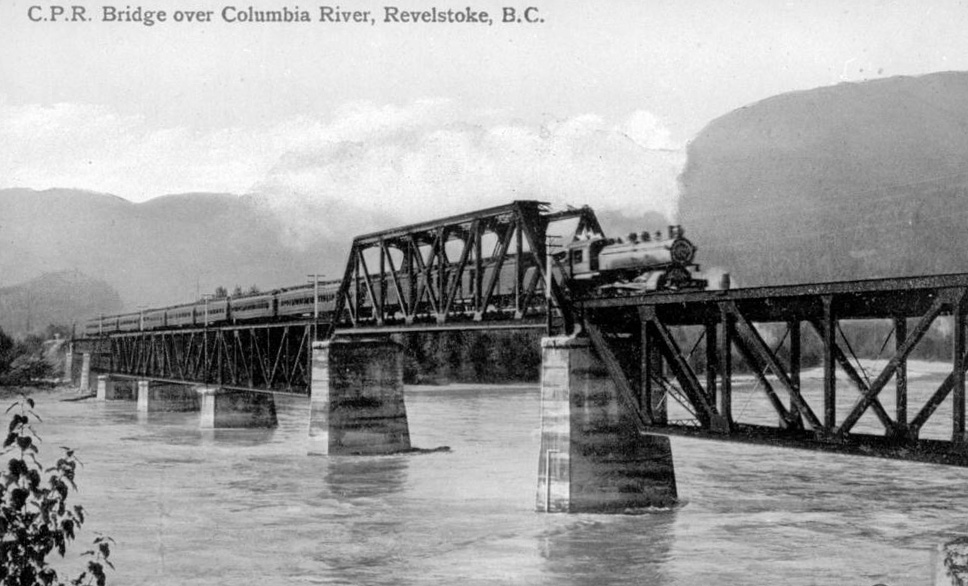

This postcard scene was printed by Canada Drug and Book Company, which existed in Revelstoke between 1897 and 1908. The wood trusses have been sheathed for reasons unknown, but this was temporary, being soon replaced. This structure would have been vulnerable to sparks from both locomotives and steamboats, and the hazard is recognised by numerous barrels for fire-fighting. This bridge was replaced by steel trusses in 1907. That narrows this photo date to the decade 1897-1907. Revelstoke Museum & Archives #1022.

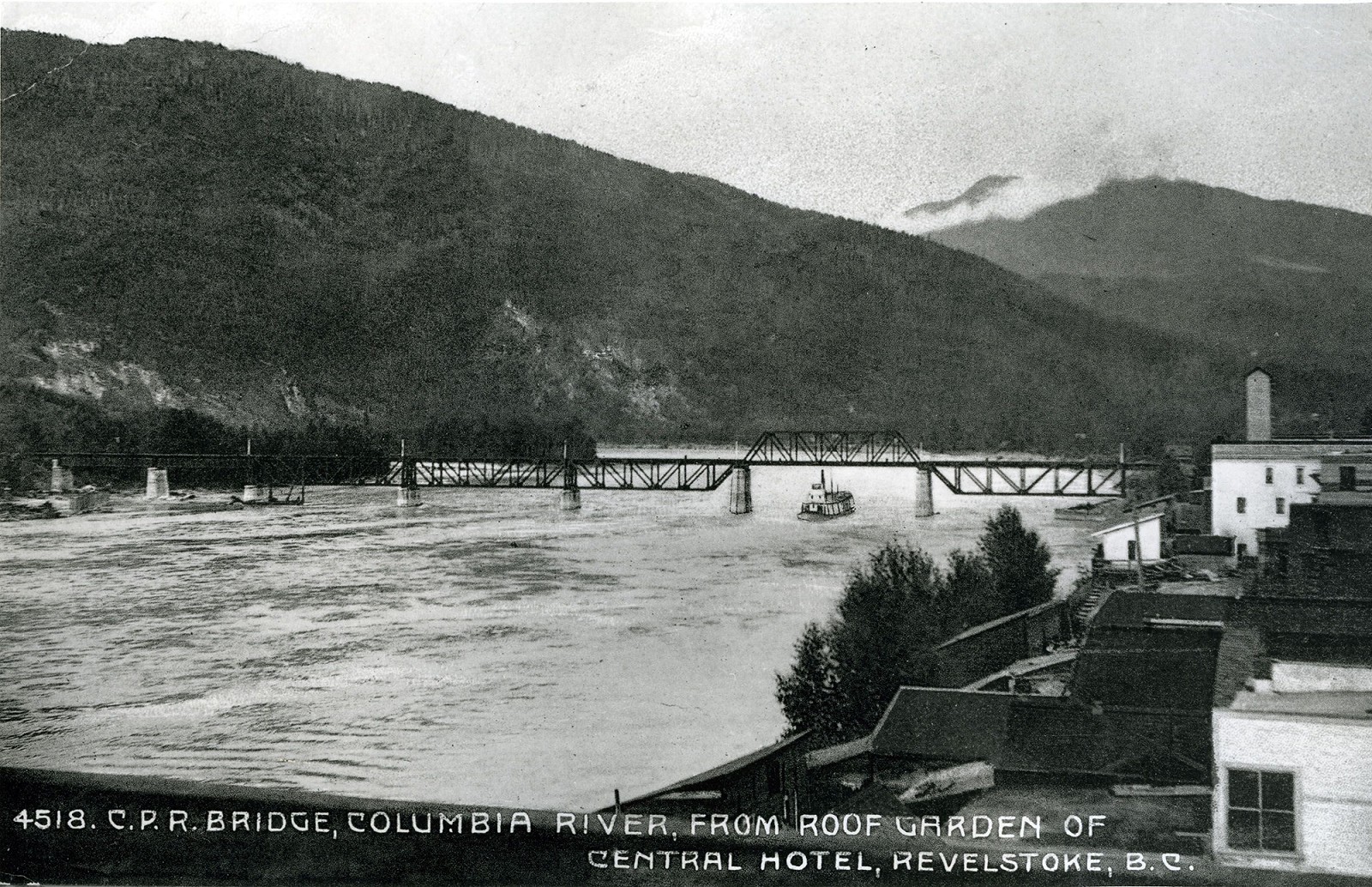

Installed in 1907, this fourth bridge later used a gauntlet track (see BC District Time Table 1935). It thus had to be slightly wider than a single-track bridge. Concrete piers have greatly improved the stability and longevity of the new structure. A cable and hook system was employed on the upstream side (out of sight) to clear logjams. This photo was taken in 1910, and was once used on postcards. BC Archives photo B-06371.

Steel and Concrete

Mount Begbie in the Monashees overlooks this lovely view of a CPKC container train heading west to the coast, 23 August 2025. The rail bridge continues to stand strong after 57 years of service. This structure is critical to the economy of all Canada. Movie © TW Parkin.

Finally, in 1907 the CPR built a steel span at Revelstoke, using concrete for piers and abutments. This bridge was among the first to use concrete, which was then replacing stone masonry as an industrial material. The earlier wooden bridge was removed after the track was realigned for the adjacent replacement. This structure stood until 1968, when I watched its replacement with an eight-span welded steel bridge, 1,122 feet (342 metres) long, then the largest welded spans on any North American railway.

Despite its fireproof structure, a 2013 deck fire proved that fire remained a hazard; it took 18 firefighters and a helicopter to extinguish the creosoted ties and timbers, but train traffic resumed the next day.

When bridge gangs reached Second Crossing in 1885, they might have thought it their last—a River Jordan for the national project. Yet in 140 years, five bridges have crossed here, each lasting longer than the last. The current span will likely be the last most readers will photograph.

Oh, there’s one more river

And that wide river is Jordan

One more river

There’s one more river to cross.

View from Front Street, Revelstoke, in the part of town once called Farwell (now “Lower Town”), viewing upstream. S.S. Revelstoke is clearing the CPR bridge. On the far shore, a pile-driver is tied up. This steel span was in place from 1907-1968, when it was replaced by the current structure. S.S. Revelstoke burned on Easter Sunday, 1915. This picture was taken pre-1910 because a road traffic bridge is not shown, but known to be in operation as of then. Revelstoke Museum & Archives #1588.

Did You Enjoy This Article?

Sign Up for More!

“The Parkin Lot” is an email newsletter that I publish occasionally for like-minded readers, fellow photographers and writers, amateur historians, publishers, and railfans. If you enjoyed this article, you’ll enjoy The Parkin Lot.

I’d love to have you on board – click below to sign up!