I Love the Smell of Fuel Oil in the Morning Memories of CPR’s Revelstoke Shops

I sometimes wonder if I should have been in the movies. Scenes from my life replay in my mind like moments from classic films. Some stay with me forever:

Napalm, son. Nothing else in the world smells like that. I love the smell of napalm in the morning. You know, one time we had a hill bombed, for 12 hours ... The smell, you know that gasoline smell? The whole hill. Smelled like ... victory.

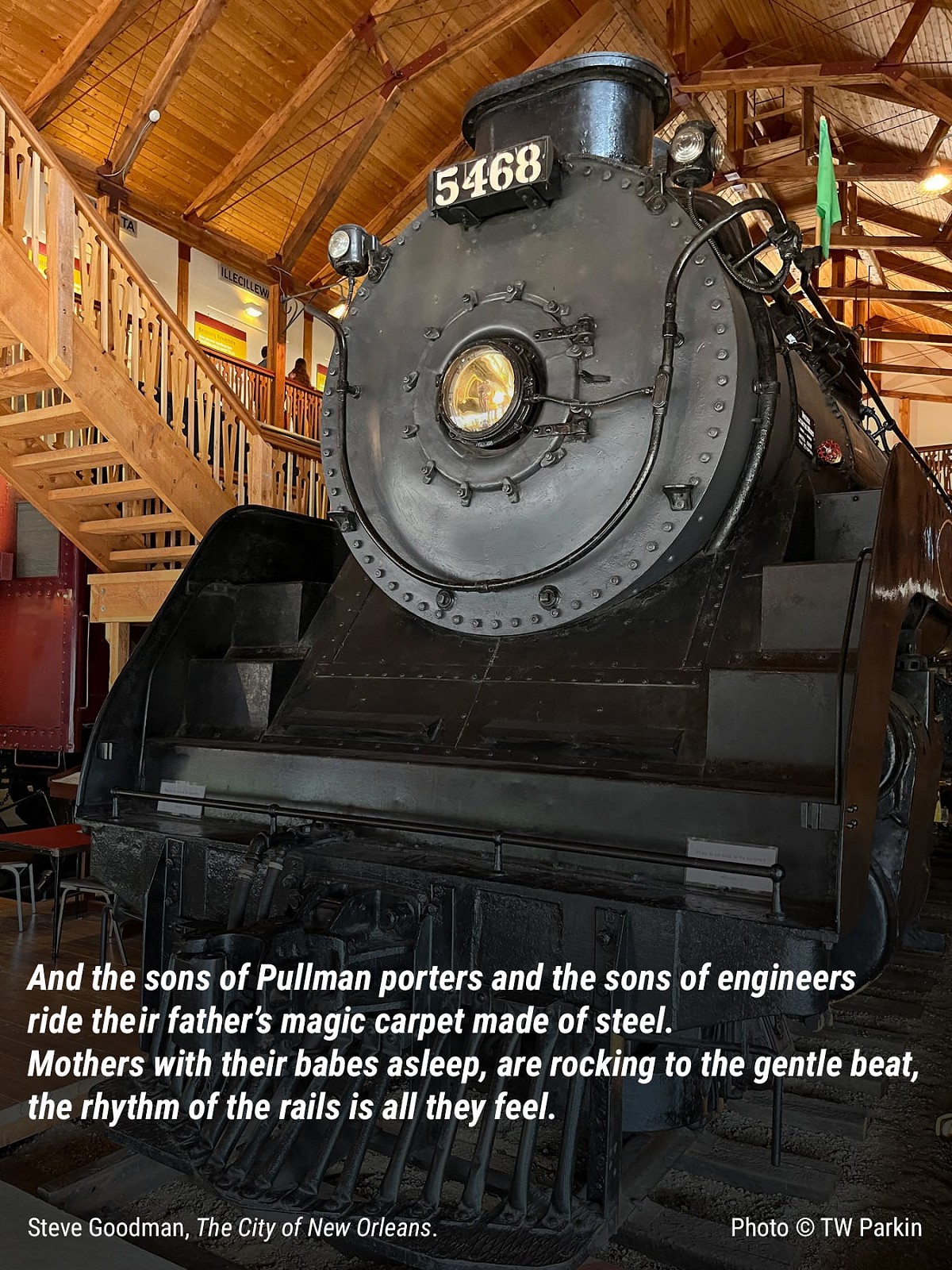

Like the evocative smell of napalm the smells of the CPR shops—spilled diesel, engine exhaust, and oil—returns my memory to a brief period of railroading in my hometown of Revelstoke, BC. I worked there during two summers in the early 1970s as a hostler’s helper. My duties included fuelling and sanding locomotives, assembling consists, and positioning them for outbound crews.

On graveyard shifts, I stood atop SD40 locomotive noses, filling their tanks with sand, while watching dawn break over the Columbia Valley. Birds occasionally sang, even in that industrial wasteland, as the air wafted the strange comfort of hot exhaust.

I never pursued a career in railroading, but the memories linger. Here’s a glimpse of the once-mighty railway shops of Revelstoke.

Fire at the Roundhouse (1897)

CP 374 survived the roundhouse fire of 1897 and was restored to service. This image was shot as a promotional photo for the 1936 film Silent Barriers (available in portions on YouTube, starting with Episode 1 here). The crew are identified as G Leedham, engineer, and J Johnson, fireman. As shown here, the engine has been cosmetically modified to appear as it did upon release from the factory. City of Vancouver Archives photo Can P88 N63.

Just about the time when churchgoers were wending their way home last Sunday evening, a prolonged wail from a locomotive at the station broke the stillness of the quiet night. The cause of the commotion was speedily reported to be a fire at the round house ... The total loss is estimated at $45,000. However, it is an ill wind that blows nobody good, and the burning of the round house will probably have considerable effect on the redistribution of CPR shops in this division, with a tendency to centralise them at this point with the greatly increased accommodation, which will now be erected in place of the burnt building.

Reconstruction began immediately, with improvements made to the design.

The foundation of the building will be solid stone and the floor will be 4-inch plank with pits of brick and cement. There will be a comfortable office for Mr Temple, and the whole building will be heated by steam, and will be altogether more complete and up-to-date than the old one. Repair shops will be erected at the back of the roundhouse, with tracks arranged so locomotives will be able to run through the roundhouse and on to the turning table in front.

By 1898, the CPR had closed its shop facilities at Donald, east of Rogers Pass, moving operations to Revelstoke and Field. This shift coincided with major upgrades, including an improved yard layout, a new station, and telegraph offices. By 1906, more shops were added, including a six-stall extension to the roundhouse.

The CPR are calling for tenders for the erection of additional shops to adjoin the present ones. The tender calls for ten engine stalls besides other buildings. About $20,000 will be spent and when completed should be the finest and best equipped along the whole CPR route.

Work is progressing rapidly with the new six-stall addition to the round house in the CPR yard, and an additional quadruple track will shortly be laid.

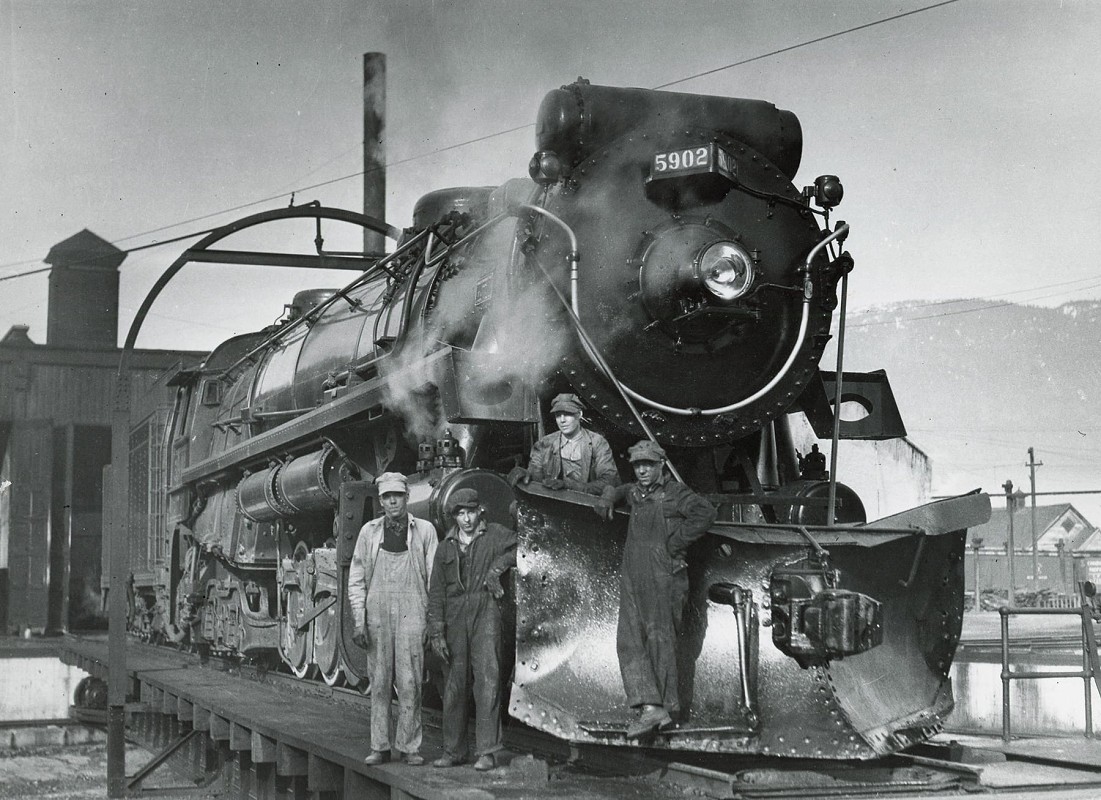

Over the next two decades, business prospered, prompting several expansions and improvements to the shops. The last occurred in 1929 when the newly delivered 5900-class locomotives—massive 2-10-4 Selkirk types—necessitated changes. These titans required nine roundhouse stalls to be lengthened by 30 feet and a new 100-foot turntable to replace a shorter one.

In western Canada, the 5900s operated between Calgary, Alberta and Taft, BC, traversing the challenging Rocky, Selkirk, and Columbia Mountain ranges. Their arrival ultimately earned Revelstoke the distinction of having the second-largest CPR roundhouse in the province.

The Final Days

Funding permitting, this classic workhorse will be repainted in its original maroon and grey livery. Declared as a National Cultural Property in 2003, it has since been placed under protective cover. Photo © JS Thorne.

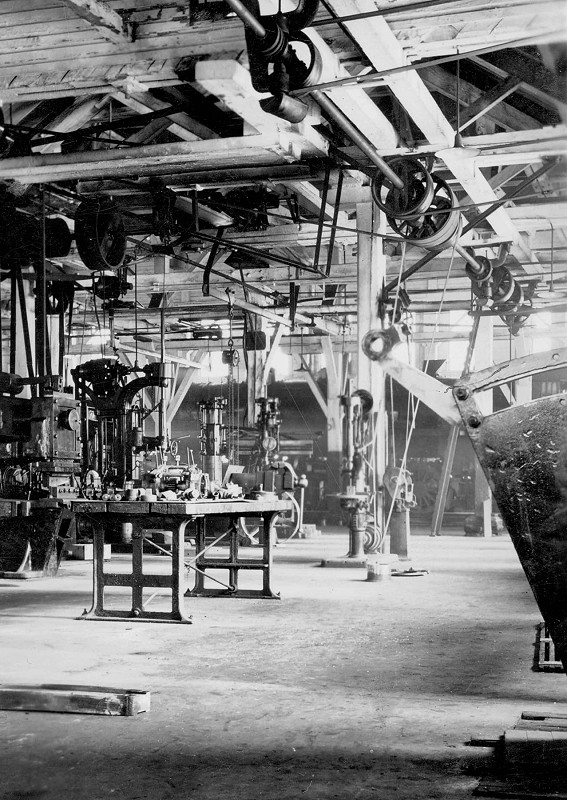

The west wing of the machine shop as it appeared circa 1920. Note the overhead-mounted belt and gear power system. The advent of electricity would have required new machines and also brought improved lighting.

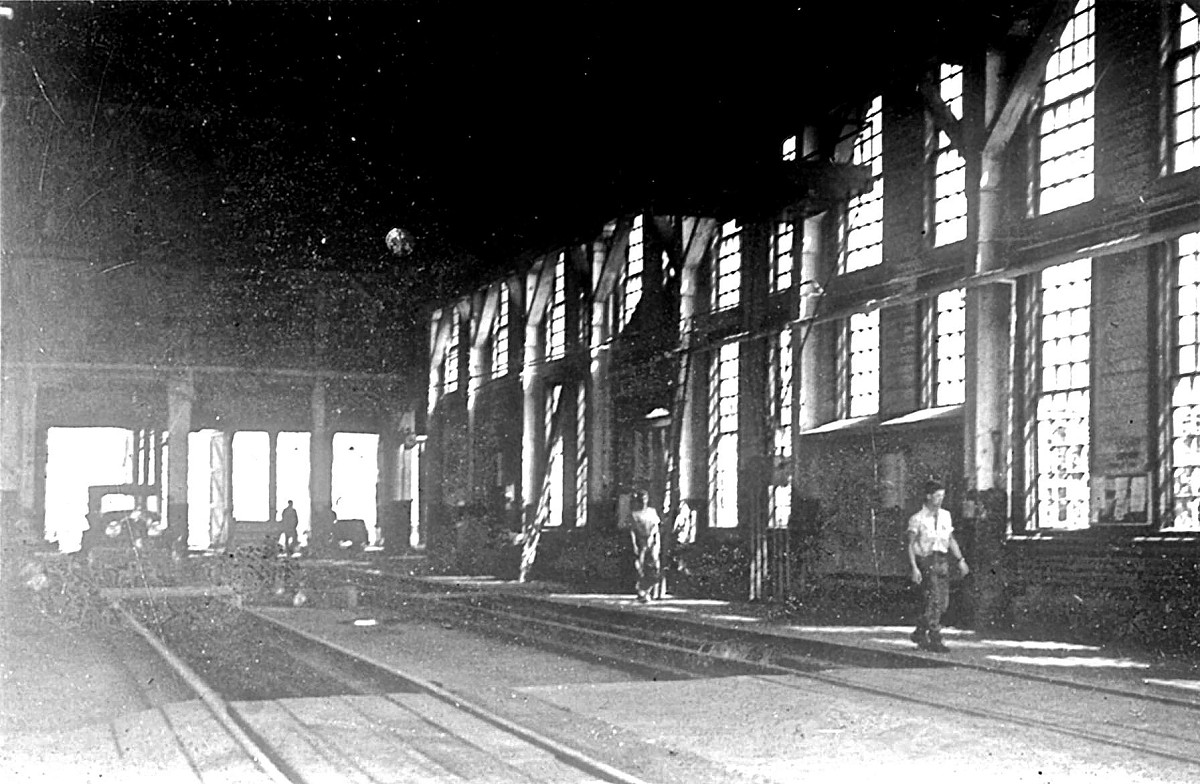

The two Revelstoke shops ‘erecting’ tracks as they appeared in 1956. The board bridges over the repair pits show in the foreground. The distant doors opened onto the turntable. The silhouette of the gantry shows against the windows. Also outlined is the superintendent’s outmoded 1927 Buick, equipped to run on rails.

To the left of the doorway lay the remnants of the old smithy. Here, coal forges, anvils, and tools of the trade seemed haphazardly arranged, though they were undoubtedly once configured for efficient work. In its early days, the shop housed lathes, drill presses, power hammers, and milling machines.

, these machines were powered by an overhead system of steam-driven line shafts. Long axles spanned the ceiling, connected by bevelled gears at their joints. Flat pulleys on the shafts held broad belts that descended to individual machines, enabling operators to engage or disengage power using hand levers.

By 1970, few machines remained, and those still operational were electrically powered. Alf Olsson, the last of the blacksmiths, worked here until his retirement in 1971. Having joined the CPR in 1942, Olsson carried on the traditions of his trade, performing welding and fabrication work, primarily for the nearby Repair-in-Place (RIP) track. “It was different work then,” he recounted. “They brought in a lot of brass and stuff like that for the locomotives, and we made the parts up right there on the lathe. We had to make whatever was necessary.”

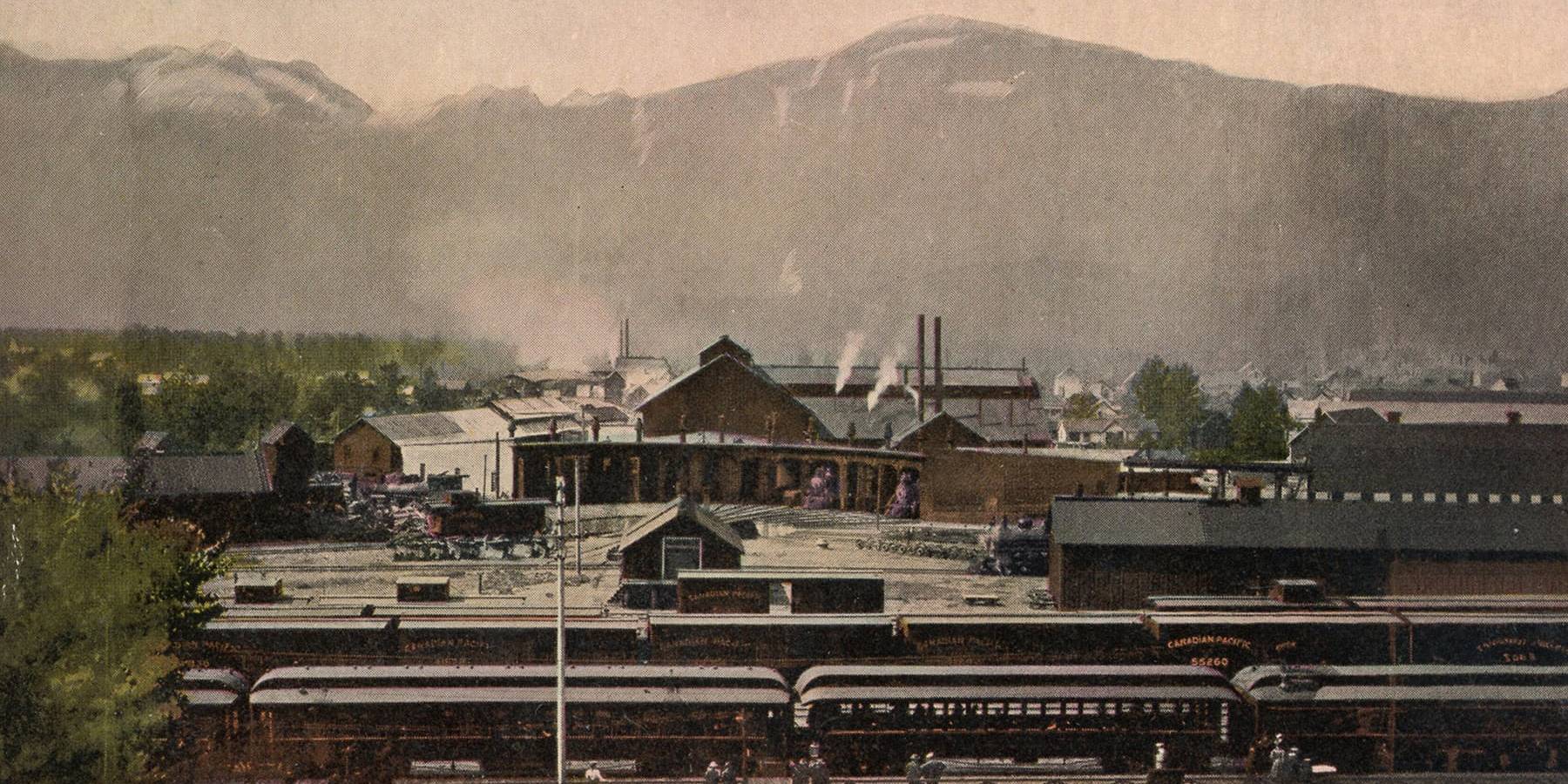

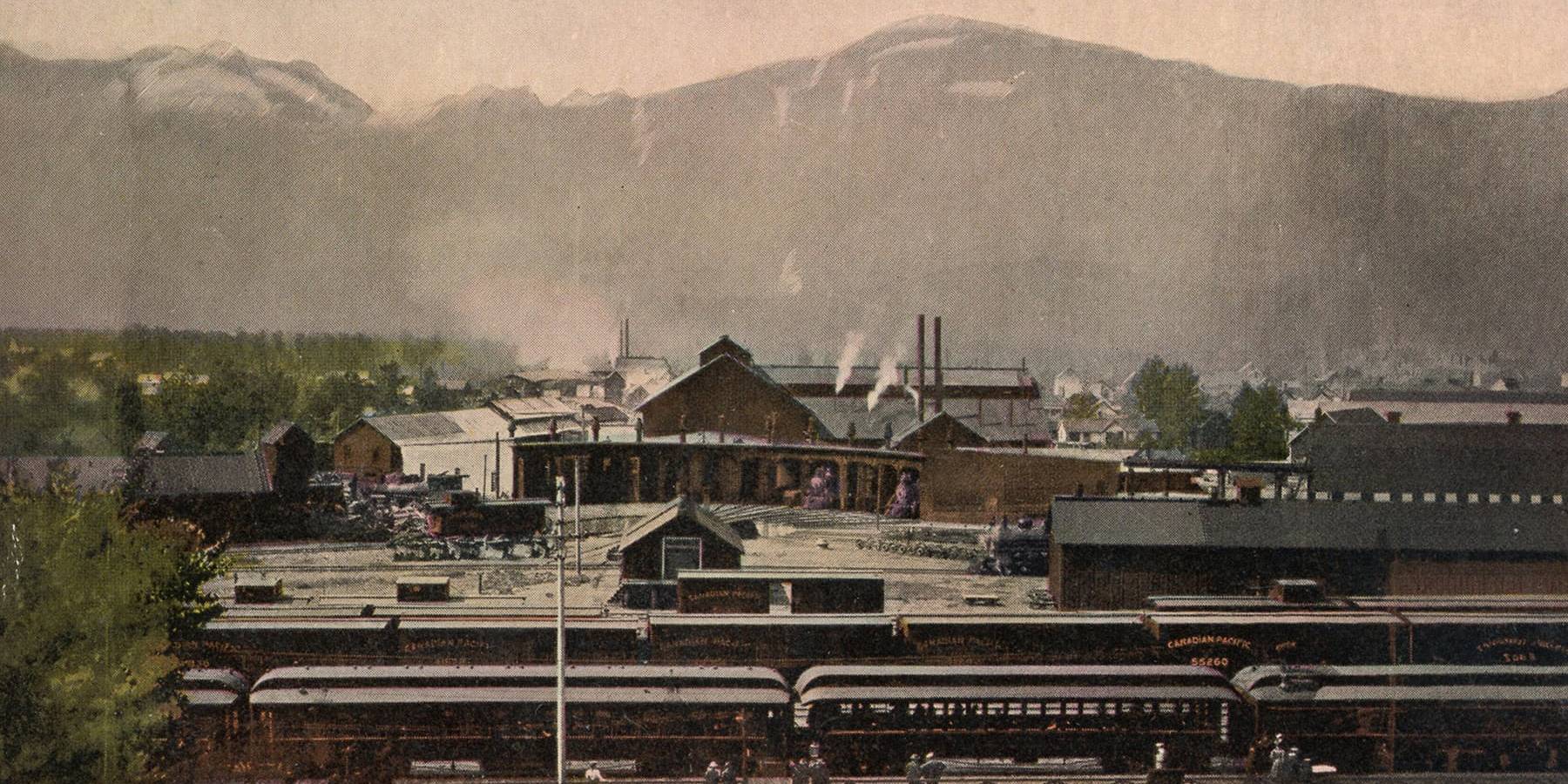

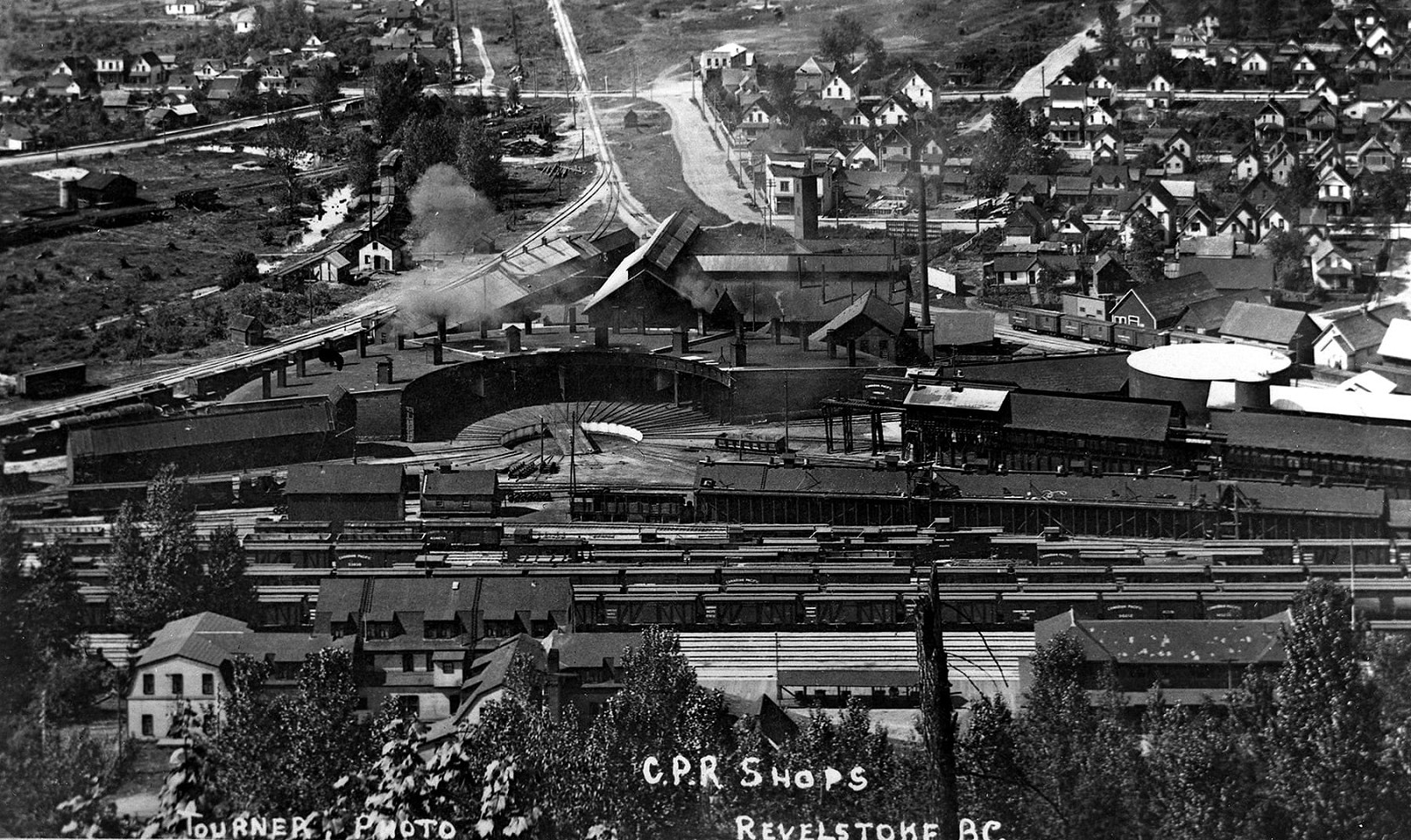

The view from “CPR Hill”, showing in the foreground (nearest left) the CPR hotel and station to the right. The RIP track is beyond the boxcars, then the roundhouse, and finally the locomotive shops with clerestory windows. Beyond the roundhouse roof are the wye and track pointing south to Arrowhead. The large tank on the right held bunker C oil (removed by 1977). Note that the brick smokestack has not yet been built – apparently two metal chimneys came first, although only one shows in this photo. Photo by AD Tourner, dated 1914.

This shop floor also held a small claim to fame: it was here, in 1920, that NR “Buck” Crump began his career as an apprentice machinist. By 1955, he had risen to become CPR’s president. Crump oversaw the transition to diesel-electric locomotives, a change that marked the slow decline of these shops because the new machines required much less maintenance. Legend has it that he once began union negotiations by snapping his suspenders at his tradesmen and declaring, “I was workin’ before you guys were born. Now, whaddaya want?”

“I was workin’ before you guys were born. Now, whaddaya want?”

Along the building’s interior right wall, a path led to the shop office. The uneven asphalt floor pooled water from numerous roof leaks. At night, sparse overhead bulbs cast isolated pools of light, leaving much of the space shrouded in darkness like a horror film set, with shadows deep enough to hide nightmares like The Shining (1980).

Further left, under a brick extension, stood a stationary steam engine. This dual-piston machine, with its large flywheel, once powered the shops and heated nearby buildings, including the superintendent’s coach, Car 19. By the 1970s, its primary role was compressing air for yard facilities like the turntable and sandhouse. The engine ran continuously, its rhythmic chuffing the complex’s heartbeat. Under load, its deep, resonant thumps echoed for blocks.

Two GP “Geeps” await assignment on the shop tracks. The elevated tank held sand for locomotives. Sand was dried in the adjacent building and blown by compressed air up through an angled pipe. On cold nights it was a comfort to hold the warm filling pipe as it drained into loco storage tanks. Photo © 1978 BG Williamson.

The shops were demolished gradually between 1978 and 1981, leaving only the boiler room, high brick chimney, and part of the roundhouse, which lasted another seven years. Photo late Dan Koronko, courtesy Revelstoke Railway Museum.

Greg Fuoco, an Italian immigrant’s son and boilermaker, tended the engine. Starting with the CPR in 1926 at 25 cents an hour, he earned nickel raises every six months.

“I was black every time I came home,” Fuoco recalled. “The soot gets right down in your underwear.” He retired in 1972, marking the end of an era.

Beyond the stationary engine lay the main repair shops, lying perpendicular to the machine shop. Locomotives entered through high, paired doors at either end, accessible from the south or the turntable. Inside, an overhead gantry crane could lift boilers off chassis, while sunken pits between the rails allowed workers to service undercarriages without crawling. Heated steam pipes lining the pits leaked in winter, creating an ethereal mist reminiscent of Hugo (2011).

Two plank bridges spanned the pits, offering a shortcut to the office

where staff punched timecards at shift changes—a small ritual in a shop

that had transitioned from bustling railway hub to fading relic.

Consolidation type (2-8-0) locomotive 1154 rolled from the roundhouse into the turntable pit, post-1903. This engine was on roster at Revelstoke in 1904, and pulled trains over Rogers Pass. Charles Henry Temple, the locomotive foreman, in the bowler hat. BC Archives photo D-04772.

CP 5902 (2-10-4 Selkirk type) on the 100-foot turntable at Revelstoke roundhouse, circa 1930. These machines marked the peak of the steam-era operations at Revelstoke shops. Left to right: Russell E Ratcliffe, Sig Lennard, Vic Crosby, and the hostler (unknown). First three are wipers or a helper for the hostler. Two later became engineers. Photo by W Hendry, Camp-Hanas-Kirkham collection.

The shop foreman, Alec Cassidy, had approved my employment at my father’s request, dad being a locomotive engineer. The CPR then prioritised hiring employees’ sons. Head-end crews booked in and out at a counter near the foreman’s office, signing off their assignments through a teller-style window. A Seth Thomas 24-hour pendulum clock, mounted in the office’s glass partition, ensured everyone synchronised their watches.

Once home to 18 steam engines, the roundhouse was barren and dusty by my time.

Crews reached their locomotives by walking the roundhouse perimeter. Once home to 18 steam engines, the roundhouse was barren and dusty by my time. Crews stopped at a desk to review recent engine logs, noting functional discrepancies for incoming engineers.

The roundhouse, built in 1909 with partially brick walls, bore scars of acidic exhaust. Its flat roof once featured funnels to vent locomotive smoke. The masonry also served as a firewall, a safeguard against fires like the one in 1897.

Outside, crews mounted their assigned engines and departed via the wye’s most direct fork to their trains. My colleague, Terry Keough, detailed his own experiences in his 2009 autobiography, My Green Age:

In the summer of 1953, the year I graduated from high school, I worked as a hostler’s helper in the CPR shops. I worked the swing shift, covering for others’ days off... The job was fun, moving engines from the shop track to the roundhouse, filling them with bunker C, water, and sand. To get it into the shops, we’d put it on the turntable until the engine pointed at the right stall. We’d then drive it in, park it, and put a chain under its wheels to keep it from spontaneously backing out into the turntable pit. Although the hostler was supposed to drive, we helpers often did the job. One of the hostlers, more often than not, arrived to work on the midnight shift three sheets to the wind. He would punch in on the time clock and then head to the superintendent’s 1927 Buick, which was parked in one of the stalls. It was a neat vehicle, which had been given a set of wheels so that it could travel on the rails. I never saw the car used by anyone except the hostler, and he used it as a kind of bedroom in which to sleep off the evening’s booze.

As psychologists note, scent and sound both evoke memory. My recollections of Revelstoke’s shops remain vivid: the tender-fingered hostler coaxing low notes from a locomotive horn, the one-lunged turntable piston straining under a locomotive’s weight, the rhythmic hiss and pop of resting engines, and the splat of raindrops through a leaky roof.

Unlike Lieutenant Colonel Kilgore in Apocalypse Now, I didn’t savour the moment.

I wish I’d asked more questions, taken photos, and experienced steam’s heyday.

Still, I feel fortunate to return to those times with you now, to reminisce.

Long may your stack smoke.

This level crossing is kept in view by a swivelling webcam mounted on the Railway Museum, 24/7. Check passing trains out here.

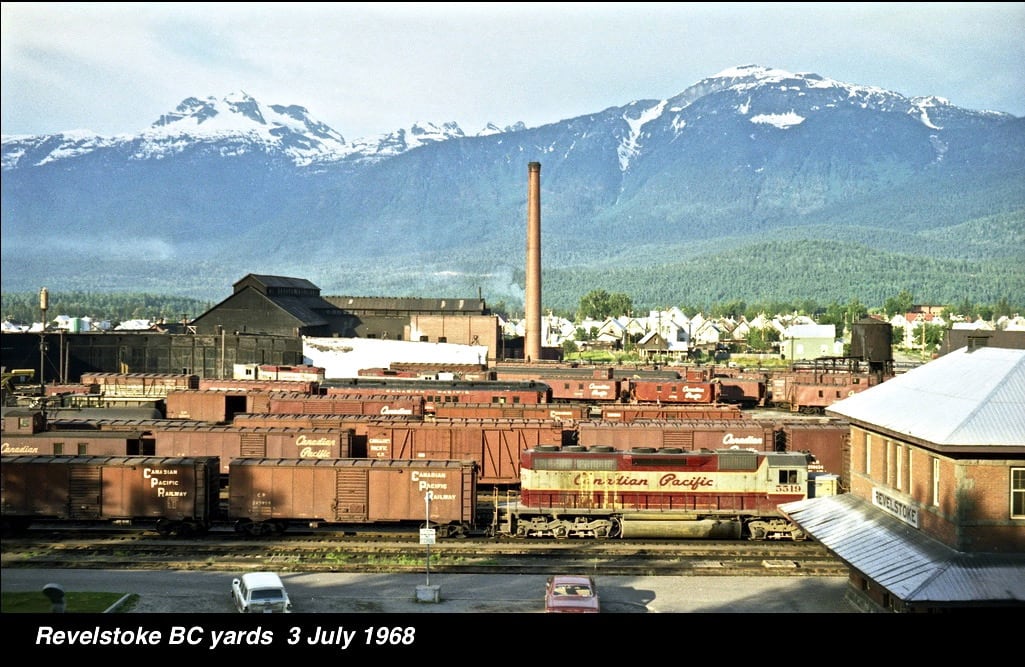

Here the Revelstoke shops stand within the context of their natural and industrial environments, as seen from “CPR Hill” on the morning of 3 July 1968. The former 1906 station is visible in the lower right while the shops blacken the mid-distance. The brick powerhouse and chimney were later constructions, and the last to be taken down. Photo by the late Don Horne.

Credits

I’m indebted to others for their contributions to this article. They are, in alphabetical order:

- Ralph Beaumont, fellow author and historian;

- The late Jack Buller who lived and loved those days of steam;

- Gordon Jones, who developed his early boiler expertise with the CPR;

- Terry Keough, whose excellent memory brought his 1950’s shops experience forward for us all;

- Doug Mayer of Revelstoke’s Railway Museum, plus Roberts Turner and Kirkham for photo assistance (not forgetting Andy Cassidy);

- Kamloopser David J Meridew for extracting the old newspaper quotes;

- And my loving primary beta reader, Mary Ann Zarichuk here in Nanaimo, BC.

Please refer to photo captions for additional credits.

Did You Enjoy This Article?

Sign Up for More!

“The Parkin Lot” is an email newsletter that I publish occasionally for like-minded readers, fellow photographers and writers, amateur historians, publishers, and railfans. If you enjoyed this article, you’ll enjoy The Parkin Lot.

I’d love to have you on board – click below to sign up!