How the CPR Saved My Family

For over three decades, late members of my family were involved with logging and lumbering in the East Kootenay region of British Columbia.

Their activity was widespread over locations in the Columbia and Kootenay valleys (also known as the Rocky Mountain Trench), involving various men and women from 1910 to 1942.

The terrain is a huge linear trough which collects drainage from the Rocky and Columbia Mountains on either side. The area under discussion is bounded to the north and south by the Canadian Pacific mainline and southern mainline, and connected through the trench by the former Kootenay Central Railway (now CPKC).

Go West, Young Man

The Parkin men were already experienced in the hardwood mills and bush camps of Lake Huron’s Manitoulin Island and North Shore when they first heard about the softwood trees of the west.

What prompted their shift of location isn’t certain, although BC’s town of Cranbrook had already attracted a former Manitoulin mill operator, who brought machinery by rail to Golden, BC, and then south by wagon. That had been 10 years earlier (1900 or so) so possibly they heard of his success at a time when their part of Ontario was already suffering population decline. It was certainly an excellent time to change locales because the west was then ‘where it’s at.’

Four Parkin brothers (Dave, Jim, John, and Wilford) are also thought to have brought their own mill parts by the Canadian Pacific. In addition, they shipped a boxcar of hardwood via the newly-completed Kootenay Central. Possibly it was unsold stock from their mill in Providence Bay, ON, or else they milled it with intent of profit ‘out West.’ This they sold to Cranbrook builders, wisely providing cash flow to help get re-established. Then they had to learn about the unfamiliar western tree species.

My family cut first growth ponderosa pine and Douglas-fir near town on land that later became the Cranbrook Golf Club.

To begin, my family cut first growth ponderosa pine and Douglas-fir near town on land that later became the Cranbrook Golf Club. Soon they were attracted south to the Moyie area. For a couple of years, the four logged across Moyie Lake from the village of that name. They owned a small sawmill on the shore. The power plant was a single cylinder steam engine with an upright boiler; equipment also utilized at their later Ta Ta Creek mill.

Many relatives found work with the Parkins over the decades, and occasionally old friends from Manitoulin who came for winter employment when their farms were quiet. A postcard written by John’s wife, Mrs. Pheme Parkin, in the spring of 1913 from Moyie states: “John and Jim are working in Porto Rico mill. Jim is millwright [and] John is helping him.”

Henderson’s BC Gazetteer and Directory for 1910 lists other brothers James and David Parkin as machinists at Wattsburg (later called Lumberton), and Jim was working there again in 1914. They worked wherever possible when not operating on their own. They were known as “gyppo loggers” in Pacific Northwest parlance, meaning they were self-employed, small-scale operators.

High Stakes

In 1916, John moved his family to take work as a carpenter at the Emma Mine near Eholt, BC. The house he bought was actually located on a mineral claim, where the rich copper boom likely inspired John at that time. Eholt was a small town near the summit of the Columbia & Western Railway in the Boundary district of southern BC, a subsidiary of the CPR. A railway branchline brought ore off the mountain to nearby smelters. So did the CPR’s competitor, the Great Northern Railway. The GN gave CP president Thomas Shaughnessy and his board of directors restless nights. But with the collapse of copper prices following WW I, John pulled stakes for greener pastures. The CPR took until 1921 to pull up their spurs to those depleted mines.

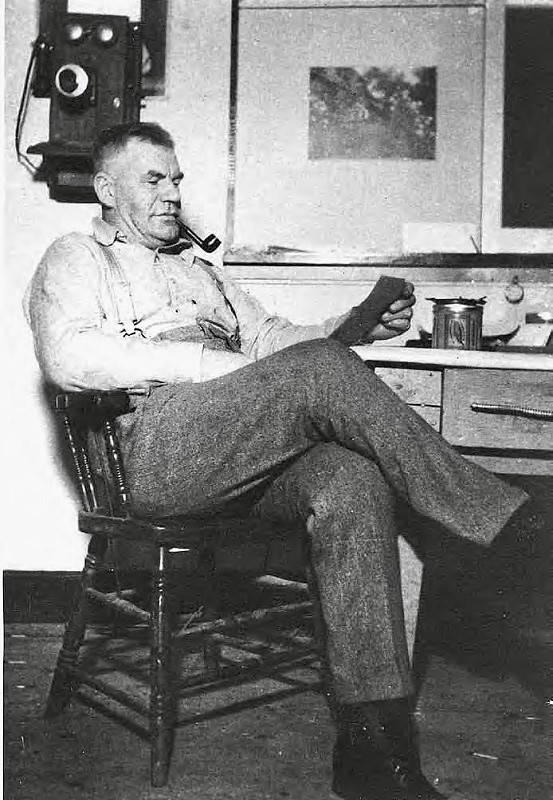

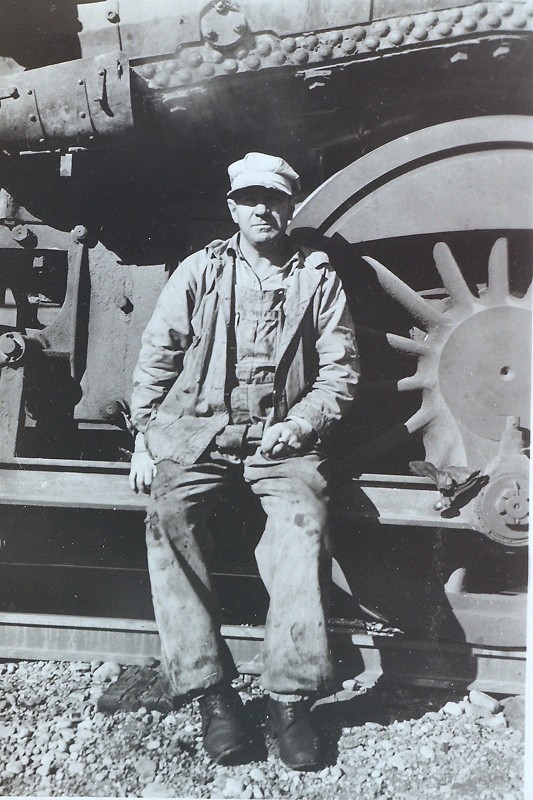

Jim Parkin in his office at Mud Creek, BC, circa 1935. Note the spent matches scattered around his chair. He was a larger-than-life character, with stories of him still told decades after his death. Parkin family collection.

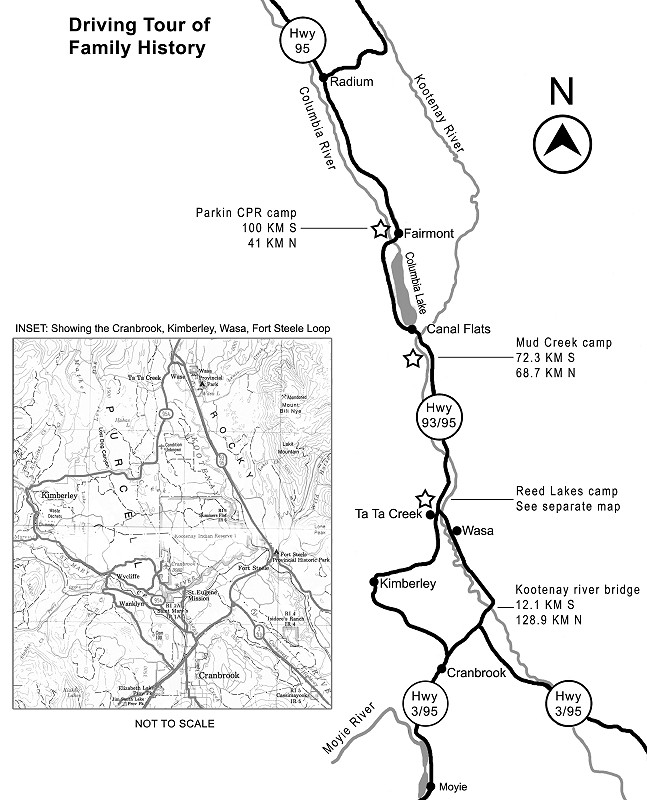

Starred locations mark former JH Parkin lumber camp locales in East Kootenay region, BC. Map © Richard Brehm.

It is brother Jim Parkin who is remembered as the entrepreneur of the family—the one with drive, charisma, and good connections. For decades into the future, it was primarily his ideas and effort which maintained family financial well-being, and much of it was CPR-related. His nephew Bill Parkin provided most of the interviews for this article before his death in 1996. For many years, he served as Jim’s foreman. Here’s Bill:

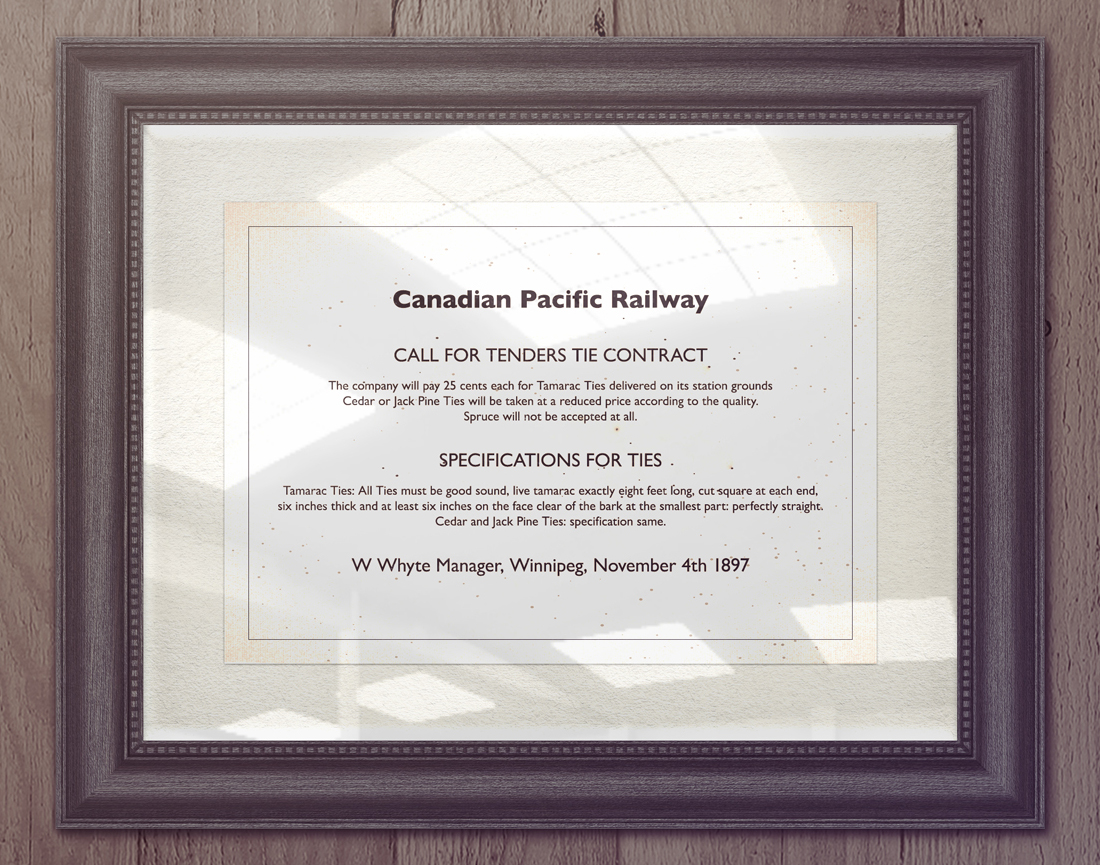

We were shut down at Monroe Lake one time for deep snow. For two or three weeks. An . . . there was a little patch a timber out from the camp. Good axe tie timber you know, that he had. So Jim said anybody that wanted to go makin’ axe ties [railway crossties hewn by hand], go out there, and they could have whatever he was gittin’ for ’em—two bits a tie. So, that was the first winter I was there; I was only 16 [in 1920]. Dad and I went together. And I helped saw down the trees, an’ cut them up, you see. And he done all the scorin’ an makin’ the ties.

I never learned to use the broadaxe ’cause he had a left-handed broadaxe. I think all them fellows were left-handed, you know. I guess it’s somethin’ to do with the guiding [hand]. If yer right-handed, yer right hand’s on the top end of the handle, you see. So we made ties for two weeks, and made good wages. But I couldn’t—I never scored one. You’d stand on top of it, and come down the log, and score it, just two hacks, certain depth with yer double-bladed axe. An’ then they come along with a broadaxe and took that all off.1

Thereafter Jim probably went to the Staples Lumber Company at Wycliffe (north of Cranbrook), where he is said to have managed their planer mill. He was supposedly fired after resisting pressure from the owner’s son to purchase a vehicle from him.2 Such oligarchy was common in those days, and nothing could be done to help refusants. But setbacks, as Jim seemed to know intuitively, often came with opportunities, especially for those willing to forge a new path.

Setbacks [...] often came with opportunities, especially for those willing to forge a new path.

A new era was dawning. Huge mills such as Staples’ that dominated lumbering of that time were reliant on their own logging railways to supply feedstock.

The highest trees and lowest railway grades near valley floors had granted them great profits. So as fibre supply diminished, large mills faced declining profits. Like dinosaurs facing sudden change, these corporate behemoths began to starve.

Foresight

Ousted into proprietorship again, Jim got even slowly by starting a small mill near Ta Ta Creek, circa 1923. For the rest of his life he owned and operated his own ‘shows’ between there and Donald, BC, further north in the Rocky Mountain Trench. His Ta Ta Creek enterprise was near what are officially called Reed Lakes, which would today be seasonally dry except for a small dam constructed by Ducks Unlimited, the waterfowl management agency. In the early 1920s however, the lakes were deeper and must have supplied water for the Parkin camp.

Life was simple and hard by today’s standards. But no one was known to complain, then or later.

The Reed Lakes mill was steam-operated of course, and logging was done by horse. The crew lived in tents and simple cabins on site. John Parkin’s family are known to have been there in the winter of 1923/24. Some say he drove team, and remembered his love of horses. His wife Pheme was cooking for the crew. Their teenage sons, Cle and Len, may have had assignments as well.

Relatives named White were present, at least for a time. Additional family again included brother Bob and wife Amie Parkin, who would come in winter from their Saskatchewan farm, along with at least some of their kids. Their son Bill never took up farming and joined his uncle Jim full time about 1927. His parents moved to BC permanently three years later to do the same thing, thankful to be off the Prairies just as the Great Depression got underway.

Life was simple and hard by today’s standards. But no one was known to complain, then or later. Work was physical and dangerous, but fun was available as well. Family and community socialization was important and more frequent than nowadays. My ancestors took part in lots of events, and knew and helped their neighbours. One nearby ranch supplied beef for the camp kitchen, plus two daughters for marriage!

Development of Portable Mills

The pine forests of this region have little undergrowth to impede logging. This made possible the use of “Big Wheels”, elsewhere known as “Michigan Wheels.” Pulled by a team of two, these wheel sets allowed one end of a drag of logs to be lifted from the ground, lowering friction for the horses.3

This method (plus sleighs in winter) was slow, but allowed logging on slopes steeper than locomotives could climb. The Staples mill closed in 1928 and its worker community of Wycliffe went into decline.

The lower-slope forests here had sparse undergrowth, allowing for the use of 'big wheels.' Pulled by a team of two, these wheels lifted one end of a log drag, reducing friction for the horses. This 'guerrilla method' competed with corporate railroads to supply logs. However, the days of low-slope, easy-access rail logging were limited. Parkin family collection.

The nearby city of Cranbrook (incorporated 1905) had long been the distribution hub of the whole East Kootenay, and lumber was central to its success. The heyday of logging was the mid-1920s when its population went over 3,000 people, but decreasingly-accessible timber and frequent forest fires soon reduced the local annual cut.

Most mills produced finished lumber that was carried out by the CPR, but a parallel market existed of seasonal workers who worked in bush mills producing railway ties, poles, and cordwood. Such small mills added strength to the economy in that a larger proportion of their cash flow was distributed as wages than was the case for other wood products.

Smaller and nimbler, such bush mills were better able to survive on declining commodity prices and volumes.

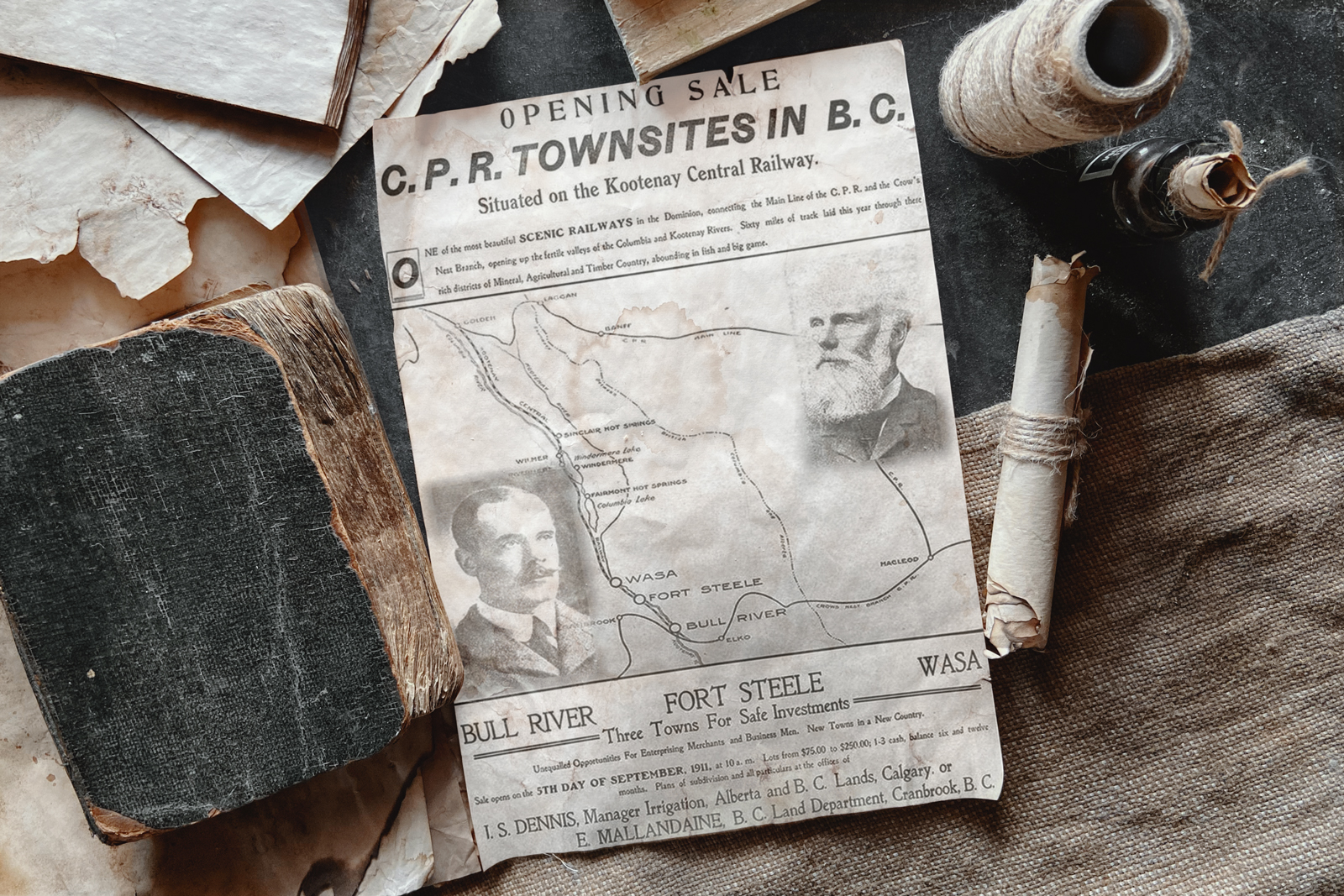

Dated 1911, this poster shows Edward Mallandaine, the boy who witnessed the CPR’s Last Spike of 1885. At this time he headed their Tie & Timber Branch.

When it first came through the region in 1914, the CPR bought most of its wood from contractors, but soon figured it could cut its own timber, cheaper. Particularly because their purchase of the charter for the BC Southern Railway included 20,000 acres of land for each mile of track constructed.

With such a wealth of resources, and cheap labour available from increased immigration at that time, the CPR organized a Tie and Timber Branch.

Much of this land consisted of Kootenay valleys packed with slopes of western redcedar, ponderosa and white pine, western larch, and Douglas-fir. With such a wealth of resources, and cheap labour available from increased immigration at that time, the CPR organized a Tie and Timber Branch from Calgary, within its Department of Natural Resources.

T&TB moved operations around in its first few years, and interestingly, its earliest agent was Edward Mallandaine, Jr, the boy photographed at the driving of 1885’s last spike! After 1913, Edgar S. Home superintended until 1943, looking after operations in Bull River, Yahk, Canal Flats and Cherry Creek, BC. Over three decades, he counted 30,000,000 ties cut for his employer.

Among his accomplishments, he told the Cranbrook Courier newspaper that he was “one of the principal developers of the portable mill, where the mill goes to the timber stand . . .”

Home was friends with Jim Parkin, and although they evidently collaborated on the design of the first mill, it was Parkin who took the financial and operational risk. Jim had acquired a timber limit on the west side of the Columbia Valley, near Fairmont Hot Springs. For a camp, he took over abandoned buildings where a horse ranch had failed. The horses had gone wild and were still in the area, so provided some assurance grazing would be available for his own animals.

The site was serviced by both road and rail, and while additional buildings were necessary, there was plenty of level ground on which to build.

Introduction of Caterpillar Tractors

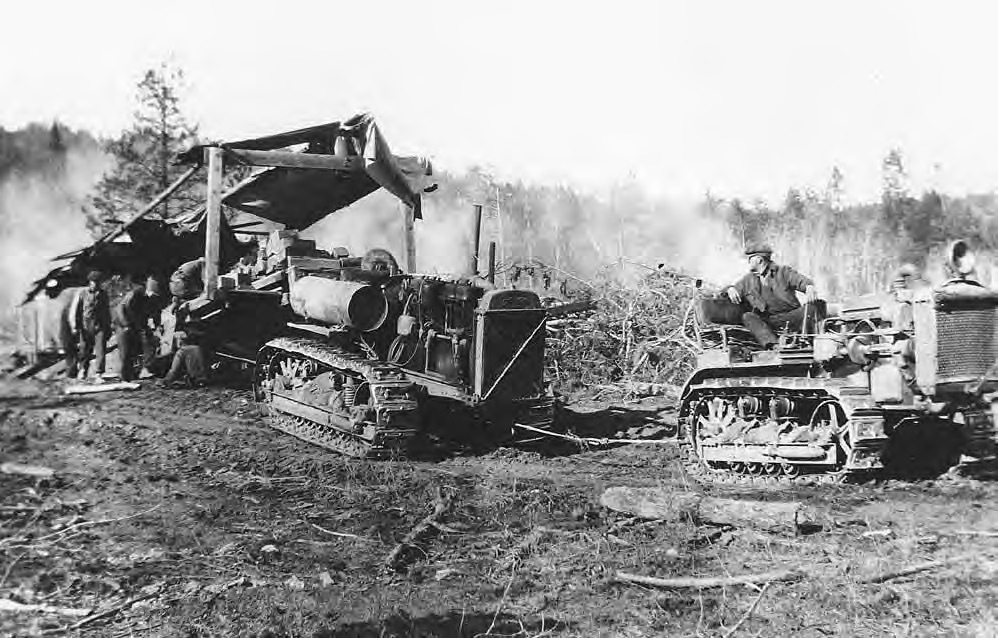

Pulling the 55-foot mill with gas Cats, models 30 (front) and 60. Doug Finnis is driving the lead machine. The crew would place poles under the runners to ease over hollows and stumps, make sliding easier. This photo probably early 1930s near Fairmont, BC. Parkin family collection.

The most significant evolution here was Jim’s approach to the wood supply. Rather than bring logs to a central mill, he took up an idea which he’d heard about elsewhere—taking a mill into the bush. This concept reduced hauling distances, saved road-building, and used a more efficient power plant—a gas-powered, wheel-less tractor.

He had bought a Cat 10-Ton soon after they came to market in 19264. He used this to both pull and to power the mill, which was mounted on two parallel runner logs. Nephew Bill Parkin was a steady employee for 15 years:

You skidded your logs in first. Years ago, it was all horse skidding, you see. And you set up, and you skidded everything you could reach with horses. Well, then you moved the mill. With the Cat. It was on runners 55-feet long. Shod with half by six-inch shoeing. And ah, that was the first [portable] mill. He had everything on it. Head gear, and tie trimmers and all this kind of stuff. [Including an edger.] He . . . built it at Ta Ta Creek. And moved it up to . . . Fairmont.5

The invention of such compact machines allowed small millers to out-manoeuvre their heavy steam competitors. Parkin’s crawler tractor sat adjacent to the mill and powered it by a continuous belt as was done with early threshing machines. When the mill needed to be moved to a fresh stand of trees, it was pulled by cable. Jim’s was the first portable mill in the East Kootenay region, and its design was widely emulated.

The invention of such compact machines allowed small millers to out-manoeuvre their heavy steam competitors.

As typical with low-budget operations, as much existing material as possible was repurposed. Although now outmoded, the big wheels were stripped of their steel tires (wheel rims), which were straightened and applied to the bottom of the log runners to reduce friction and save the wood from wear.

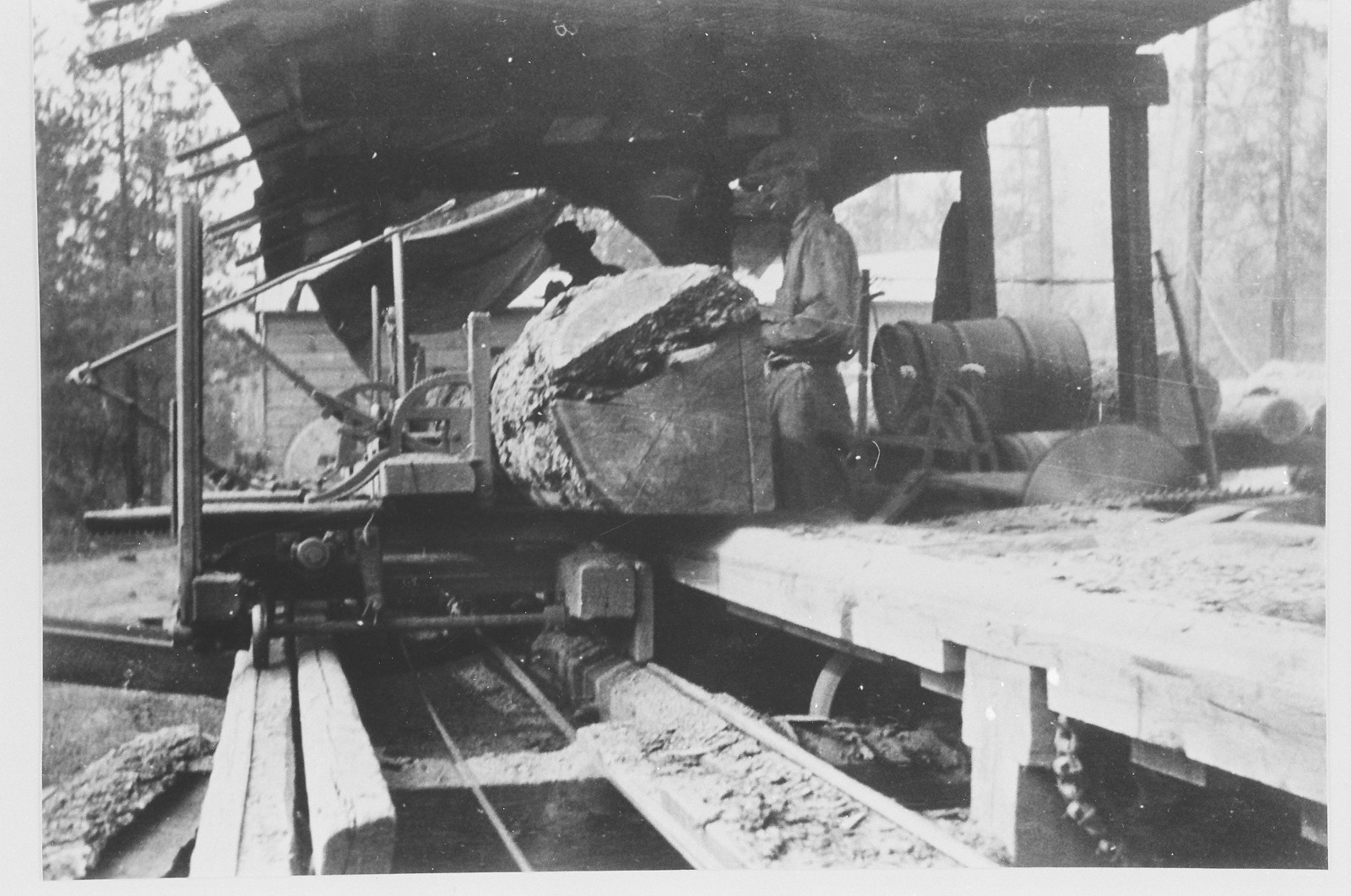

The mill carriage holds and pushes a Douglas-fir log through a circular saw (not showing), creating a wide plank. The dangerously exposed trim (cut-off) saw spins on the right. Parkin family collection.

Jim didn’t conceal his advantage from competitors. Nephew and employee John R. Parkin said the Cranbrook Sash and Door Co. subsequently adapted two of their units for lumber production on Baker Mountain at Cranbrook (where John also worked).

They used small gas engines, but added a flywheel to give the saw needed momentum. Since they didn’t have tractors to move the mill, they added a hoist to the frame and used snatch blocks so it could pull itself around by cabling to distant objects and winching itself along.

The idea quickly caught on. Home soon had six mills of his own working along the Kootenay River upstream from Canal Flats. This, and other area rivers, were used for ‘drives’, just as done in eastern Canada.

The Cranbrook Foundry, which had been customizing units for the differing needs of its customers, began to market a ‘Standard’—their own off-the-lot design. In 1930, Vancouver Machine Works advertised in the B.C. Lumberman that they had sold 70 of their units to satisfied customers.6

Portable Mills During the Depression

Better times didn’t come, of course—the Great Depression was underway.

As the decade progressed, most bush mills produced railway ties and some rough lumber. The ties were sold green to the CPR and the lumber was shipped to nearby planer mills for finishing and drying. The heyday of the tie business in BC extended from 1920 to 1929, with production usually over three million, and peaking at 3.8 million in 1921. In 1929, tie output from the BC southern interior was 1.2 million pieces, comprising 10.3% of the dollar value of that region’s total timber operations.7

But production kept dropping. The B.C. Lumberman lamented the state of the market, but maintained its perennial expression of hope for improving prices and production.8 Better times didn’t come, of course—the Great Depression was underway.

The 1930s became a decade of pay-by-the-piece operators, usually selling to the CPR.

The 1930s became a decade of pay-by-the-piece operators, usually selling to the CPR. Under the management of Edgar Home, the T&TB also let contracts to independent lumbermen. Jim Parkin signed contracts with Home, but the two were also on personal terms because Home rented a heritage home called Tower House as his residence between 1920-1942. It was an upscale residence the Parkin boys had built collectively soon after arriving in Cranbrook, but which they occupied only briefly themselves due to the transitory nature of their work.

Bill Parkin again: We ran all through the Hungry Thirties and never lost any time at all. We had a contract for a hundred thousand ties a year.

Such contracts would typically be fulfilled in about nine months of work over a winter:

I remember one time there, at the Crow’s Nest [Crow’s Nest Pass Lumber Company], they were just loggin’ near the same locality we were. They were 40,000 ties short on their hundred, when the time was pret’near up. So we took that contract from them. And put our little sawmill in there, and made an average 520 ties a day.9

The crew would usually consist of a sawyer and his helper, who manually moved logs along the infeed deck, onto the carriage, and through the saw. The log would then be passed to a tail-sawyer and his helpers, who would trim the ends, move and stack the ties, and pile aside slabs cut from their sides. Additional men would be employed on logging and hauling operations. Sometimes those with families were given accommodation.

If you needed a job and had a friendly or family connection with Jim, he provided work if he could.

The 1930 Directory of BC shows 20 men living at Fairmont Springs, but women and children known to be there were not inventoried because they weren’t employed. In total, there could have been 30 people living in camp at that time. Bob and Amie Parkin located their house on the opposite side of the railway tracks from the rest.

If you needed a job and had a friendly or family connection with Jim, he provided work if he could.

Men Worked Hard

There was a difference now from past camps. Family women no longer cooked for the crew. This was probably due to their age and maternal obligations. But business success in part depended on retaining men by having a good cook. Another nephew, Dave Parkin, worked as a kitchen flunkey as a teenager and mentioned the characters around camp:

We had the best food money could buy. We couldn’t pay much, but old ‘Monk’ Urbanks was one of the best in that country. He used to cook for Otis Staples.10

Monk had a wooden leg, and was known for astounding visiting children by stabbing himself in the thigh with a paring knife after peeling potatoes, and then walking about quite unaffected!

Another relative employed by Jim was this author’s father, Cleland. He did various jobs between stints with the CPR to keep steadily employed while progressing through the spare board as fireman, and then engineer. He told of lifting green railway ties eight feet long onto each shoulder in order to stack or carry them up a bouncy plank into boxcars.

Bill Parkin:

Them days they had to be strong . . . well, it all had to be picked up by hand. And walked up a plank into those cars. Those guys that were loadin’ ties, those number two ties, they used to pay a man by the day to stand them ties up two at a time for [the packer], to walk up that plank. But the average weight of a number two is 120 pounds [55 kilos].

Oh they’d pack ’em on their shoulder, eh? We used to make a pad. You’d git, I don’t know you ever seen those old pads—sweatpads—for horses? Under the collar? We used to take one of them and split it; they’d put it on a chunk of leather, one in the front and one in the back.

Oh yeah, it all hadta go out by rail. There was no big trucks them days, that ’mounted anything, you know. When we first started at Fairmont, we went back into the bush about three miles I guess, was furthest. There was no way of gittin’ your ties out of the bush, only by usin’ the Cat that you were usin’ to power your mill.

So we bought three of these Athey wagons. They’ve a track on the back, and wheeled front. They’re supposed to be 10-ton wagons. An’ I spent all my Saturdays and Sundays haulin’ ties out of the bush! Besides, by this time we were skiddin’ the logs with the Cat too, in the bush. I never got a Sunday or a Saturday off. It was all just straight time, you know.

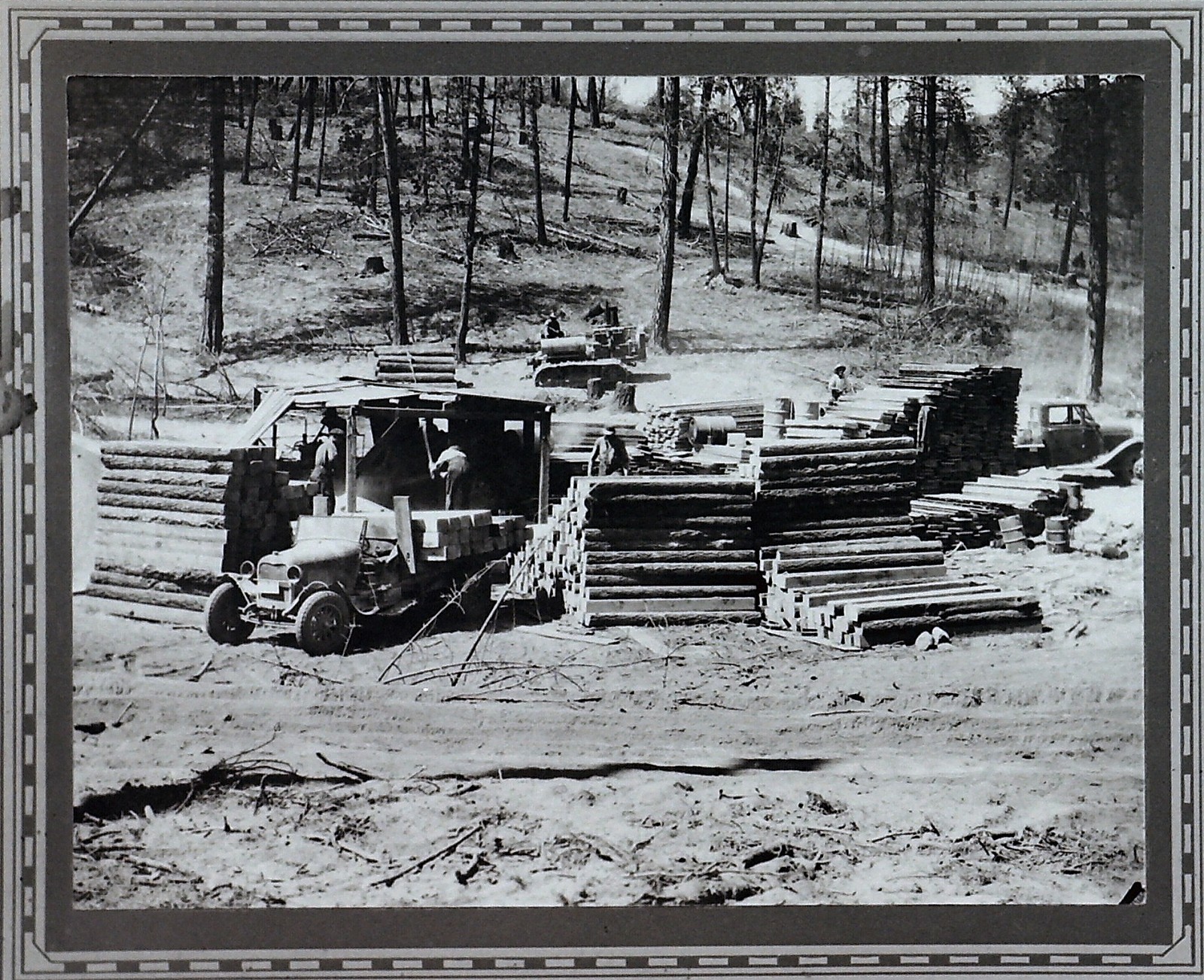

Harold White and son Bill loading ties for transport to CPR siding. Bill recalls: Yeah, that‘s the first truck we had. 1929. You know, when we bought them trucks, there was no cab on them. No seat or anything—just the framework and the motor. You had to go scarf the body off an old car to get a seat and a windshield. We had four trucks. Parkin family collection.

Bill Parkin on the Cat 60 hauling Athey wagons loaded with snow fencing up a ramp beside a CPR siding, bound for boxcars. Onlookers worry about the dragging wagon tongue, damaged in transit when the front truck on the lead wagon overturned. The repair required unloading, so to save effort, the load was chained directly to the Cat’s rear. Athey wagons could carry 10 tons and had a dual-tracked rear wheel set. Parkin family collection.

Happy Just to Have a Job

This shift in equipment marked a significant transition away from traditional methods. Only “one or two” horses were retained for light work when machinery was inefficient. The mill used two Caterpillar crawler tractors: a gas Model 30 with 30 horsepower and a larger Model 60. With them, the mill was able to cut larger logs (38-inch as compared to standard 32-inch circular saws): Well, we always had the best of equipment, you see.

But while quick to innovate, Jim also retained his old-fashioned horse sense. When diesel tractors were first offered in the mid-1930s, he and Bill crossed the border to Spokane, Washington, to visit a dealer:

They started one up in the shop, and you know how they rattle? When they’re idling, they just sound like they’re goin’ to fall to pieces, you know. Jim walked around and around that Cat. ‘They’ll never sell,’ he said. ‘They’ll shake themselves to pieces. Just listen to that’. He wouldn’t have anything to do with it. Two years later, well, we had a new D-8. And D-6.11

Bill Parkin operating a model 60 gasoline powered Caterpillar at his uncle Jim’s bush camp near Fairmont, BC. The machine is in near-new condition at this point. The canvas roof and seat cover were usually the first to go. That soon left me sittin’ on a sack of hay and a board for a seat. It sure shook the insides out of me. By 1933, I had to quit drivin’, you see. It bothered the joint in my backbone. They couldn’t do anythin’ about it. So I quit and stuck a big wide belt on me. I wore it for years. Like a corset, you know. Parkin family collection.

In subsequent years, Caterpillar revamped their entire model line and made mechanical improvements to the diesels. The D-series (1938-1959) became internationally synonymous with size and power. They were key to the Parkin success.

The best count we ever had was 613 ties/day. That was only . . . five men on the tie mill. And then there’s all the other men gettin’ the logs to the mill, and hauling all the ties away. Sometimes I wondered how the hell we even make profit; 32¢ for a tie, and 8¢ apiece a mile [for truckers to haul] to the railway. That was a big cut in that 32-cent tie.

A year or two after I quit, the unions come in. Guy had to pay overtime and all this kind of thing. Old Jim would have had a fit. Yeah, I never got any overtime or anything. [We worked] as long as you had something to do, that’s all. Again, there was something always to be done after supper. And Jim used to do the blacksmith work himself. You would go work with him if he had something to do. And Sunday would be repair day. Once in a while we would take a notion to move the mill on a Sunday.

In July 1931, a massive forest fire scorched 14,800 hectares along the west side of the Rocky Mountain Trench, starting near the present-day airport between Cranbrook and Kimberley and spreading northward. The Parkins, logging in the area, were called to help fight the blaze. Although the community of Canal Flats was evacuated, a last-minute shift in the wind saved most homes, with only a few on the outskirts lost. Remnants of the fire smoldered until fall.

To prevent insects from ruining the standing timber, the Forest Service directed the Parkin mill to relocate to the so-called "Black Camp" on Thunder Hill, above Canal Flats. They likely stayed there less than a year, living in primitive shacks they built, fully aware their time was limited.

From Parsimony to Profits to Prevarication

Parkin portable mill operations, possibly at Mud Creek camp, BC, 1932. Bill Parkin, cat skinner, poses in the background while dragging in a new load. The Caterpillar Sixty was a 60 horsepower gas machine made by Caterpillar Tractor Company from 1925 until 1931. The Sixty was the largest in their product line at that time. Parkin family collection.

In 1933 the camp moved again, this time to Mud Creek, a small stream which crosses Highway #93/95 about five kilometres south of the village of Canal Flats. Here they remained for six years because their timber limit was 2,400-2,800 hectares. They built this camp ‘from scratch’, but knew it was impermanent, so again, form followed function. The cookhouse was situated over the creek so water could be dipped through a trapdoor in the floor. All buildings were rectangular with board walls, small-diameter ridgepoles, and with roofs slightly cantilevered to cover a single door below the gable. Heat was provided by wood-burning cook stoves. Some interiors were wall-papered, which helped keep out drafts.

They built this camp ‘from scratch’, but knew it was impermanent, so again, form followed function.

Within a few years Jim was feeling easier about his financial situation and was spending large amounts of time away from camp. Bill Parkin became foreman and ran operations in lieu. Jim was spending his profits and dabbling in the stock market. One day he phoned from Calgary with instructions to take a share certificate out of his safety deposit box in Cranbrook. The stock was for the Foundation Company gas well which had just ‘blown in’. Jim may have pocketed as much as $65,000 on that trade. It was a tremendous sum in those days.

With it he bought a new D-8 Cat, worth $8,600. This was Cat’s first diesel sale in the Interior, and Bill went to technical school in Vancouver for several months to learn how to maintain it. This machine was used primarily to power the mill, but the company proudly recorded that Jim bought the first power winch in the region as well. Later that same year he purchased a D-6 ($5,500) to replace the old gas Model 10.

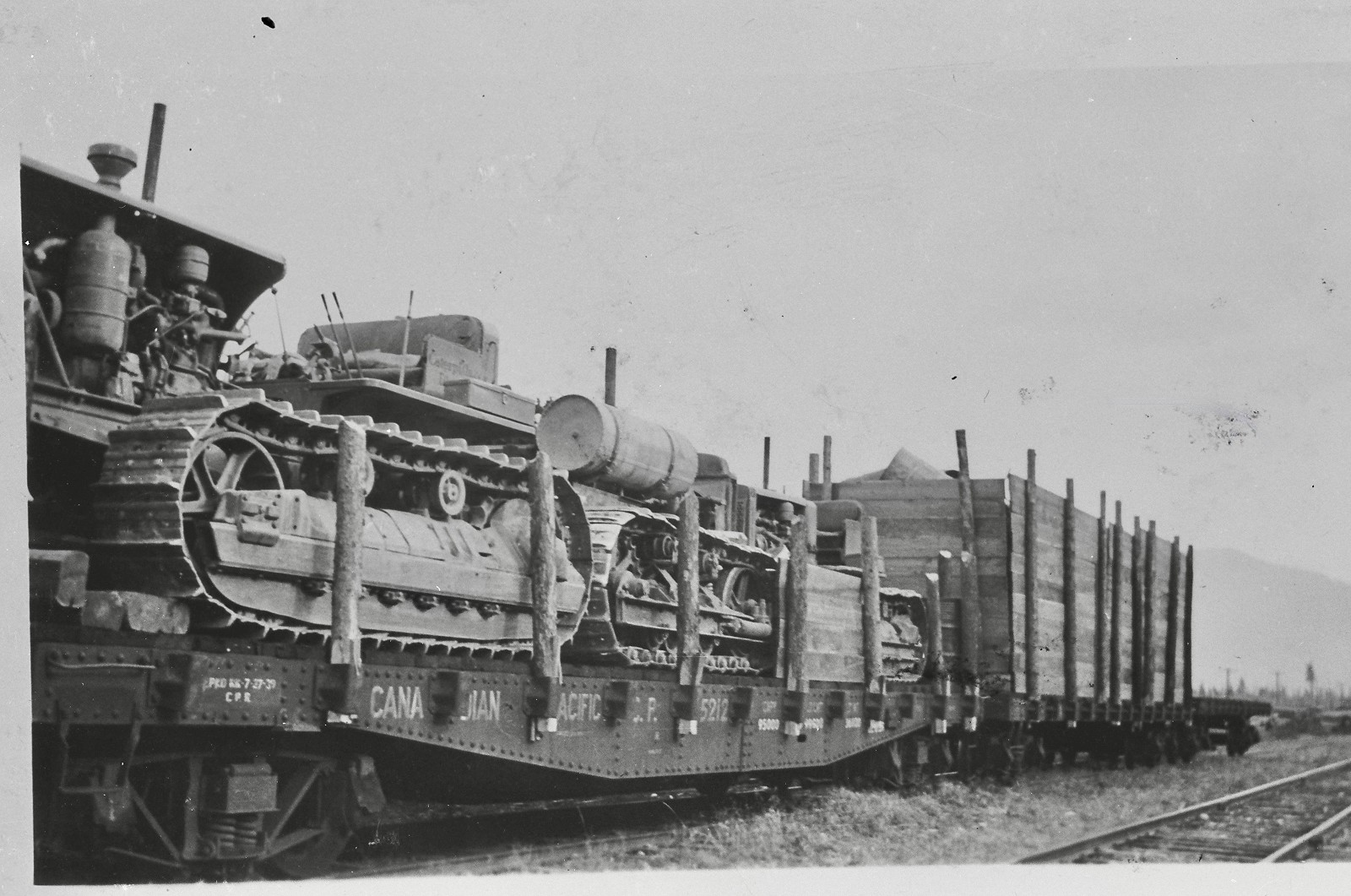

Three Caterpillars and camp gear bound from Canal Flats area to Donald, BC. Service date painted on CP flatcar, 27 July 1939. The smallest machine at the back was missed by the CPR inspector. Parkin family collection.

In the summer of 1939, when the Parkins were moving camp due to their exhausted timber limit, Jim prepared to relocate to Donald, BC, where he had purchased a defunct sawmill on the CPR mainline. They ordered two flatcars for their equipment: one for the disassembled mill, spare parts, and tools, and the other for three Caterpillars.

Knowing the second car was overloaded, they wanted to avoid the cost of a third car an inspector would surely demand. Hearing that a CPR official was to visit the next morning, they rose early to remove one Caterpillar and hid it in the bush, loading it back after the inspector left. Fortunately, the journey north proceeded without incident.

Snow and Cash Flow

JH Parkin’s mill at Donald, BC, operating posthumously between 1942-47. A passing locomotive, likely a 5900, T1b class, can be seen. Photo courtesy of Golden Museum. Photoshopped by JS Thorne.

The author’s father, Cle Parkin, taking a smoke break on the siderods of CP 582 at Golden, BC, in 1949. Cle was engineer on the Kootenay Central wayfreight at the time. Despite his strength, he never regretted leaving his uncle’s mill for railroading. Photo © late Ernie Ottewell.

At Donald, the CPR siding had previously been a Weyerhaeuser Timber Company operation. The Parkins took over a large warehouse and dragged it away to renovate as the camp cookhouse. All other buildings had to be built, including a large framework for a planer mill, which was a significant addition to their operation. It sat right beside the track, so eliminated the trucking necessary with the bush mills. Jim was planning to now sell lumber. John Parkin was instrumental in erecting this structure.

From photos, it appears they didn’t get it roofed before snow set in. That first winter was harder than anticipated. The snow in this region was heavier than any other they had worked. They were unable to manoeuvre in the bush, so their strategy to maintain cash flow was to run the portable mill right in camp, and to have local farmers truck in logs that they cut on their own property.

Workers were hard to get because WW II had started, and even two of Jim’s working nephews left to enlist in the Canadian army.

Summer production also seems to have been hampered by wet weather which probably turned haul roads into mires. Workers were hard to get because WW II had started, and even two of Jim’s working nephews left to enlist in the Canadian army.

Alex Stuart, the bookkeeper, was an ex-CPR employee. He joined Jim in 1939, also to act as lumber-grader and shipper. When the crew accidentally knocked down telegraph lines along the right-of-way, he knew CPR officials would soon be out to investigate, suspicious of enemy sabotage. Stuart told Jim to get three or four bottles of liquor to help smooth relations. The tactic worked. They all went away singing, said Bill.

Another time, Stuart learned the CPR weigh scale at Calgary was inoperable. Don’t know how he found out, said Bill. But during that time we just plugged them boxcars. Bound for Calgary lumber yards, such cars had to stay below a defined carrying capacity.

It was the end of an era, both his own and that of portable mills in general.

Jim managed to avoid extra costs those times, but operations had become an ongoing challenge. Cash flow slowed. Then, suddenly, Jim died of a heart attack in the spring of 1942.

It was the end of an era, both his own and that of portable mills in general. His business was taken over by a rapacious relative who fired all the family and supplied his own lumber yards in Calgary with product from Parkin Spruce Mills.

Truck logging was coming in, and such vehicles were able to supply bigger, centralized mills once again. Bill moved on to be a mechanic elsewhere. My father, pleased to be declared of essential service (and thus avoiding potential conscription) enjoyed a long career operating locomotives on the Kootenay Central and on the mainline between Revelstoke and Field, BC.

Born in 1951, I missed it all.

Jim was gregarious and generous to the point others took advantage.

My great uncle Jim was certainly a man’s man. He drank, smoked, and womanized until he married at age 56. Although opinionated, he connected easily with others of influence, and as a Freemason, with those who practised brotherly love. Jim was gregarious and generous to the point others took advantage.

Yet his entrepreneurial effort kept his extended family employed through periods when they didn’t have work, especially during what author/historian Barry Broadfoot called Ten Lost Years. Jim created a connection with the Canadian Pacific Railway that endured for two generations beyond his own.

I wasn’t there, but am proud to tell you of it.

Factoids from Factors in Railway and Steamship Operation

Canadian Pacific Railway Foundation Library (1937)

Chapter “Sixty Million Canadian Pacific Ties”

by J.H. Reeder, General Tie and Lumber Agent

- There are 60 million ties in the track of the CPR and its Canadian subsidiaries.

- Yearly replacements up to 1930 [start of the Great Depression] was 6 million ties

- At present [1937], annual requirements are 3.5 million, or 10,000 carloads.

- The company has its own operation in BC which produces 1 million annually.

- All species are used, including hardwoods in the east.

- Hewn ties are still being accepted, and are seen as a way of supporting small farms.

- Three grades are used, each with specifications, and are placed thusly:

- #1 mainline and on curves of first-class branch lines,

- #2 on sidings and spurs, and

- #3 do not meet #1 or #2 requirements, but are used as #2 replacements.

- In an era of lighter traffic, cedar ties [a softwood] had lifespans of >20 years.

- Cedar became difficult to obtain, and other species gave a service life of ≈10 yrs.

- CP first tested creosote ties in 1906 and 1909, calculating their lifespan as 30 yrs.

- As of 1937, 50% of company ties were being creosoted, all at Canadian plants.

- Four to five pounds of creosote per foot3 of seasoned wood protects from decay.

Endnotes

- Taped interview with Jim’s nephew Bill Parkin, 16 February 1992, Noric House, Vernon, BC.

- From interview by TW Parkin with WM Parkin, Noric House, Vernon, BC, 23/4 April, 1994.

- Big wheels had no brakes, so could not be used on slopes exceeding 15%. Their use was limited to summertime, when a teamster had to walk or trot 10-18 kilometres in a 10-hour day.

- History of all early logging equipment in this book drawn from Endless Tracks in the Woods by James A. Young and Jerry Budy, ©1993, Motorbooks International Publishers, Osceola, WI.

- From interview by TW Parkin with WM Parkin, 16 February 1992, Noric House, Vernon, BC.

- However, Parkin’s design is credited as being the basis for virtually every portable mill subsequently operating in the East Kootenay. See British Columbia Lumberman, Vol. 26, #6, June 1942, p. 40.

- Province of British Columbia, Department of Lands, Report of the Forest Branch, 1937.

- J.R. Poole, British Columbia Lumberman, Vol. 14, #2, February 1930.

- Taped interview by TW Parkin with WM Parkin, 16 February 1992, Noric House, Vernon, BC.

- From interview by TW Parkin with RDH Parkin, at home, Cranbrook, BC, December 1993.

- Taped interview by TW Parkin with WM Parkin, 16 February 1992, Noric House, Vernon, BC

Did You Enjoy This Article?

Sign Up for More!

“The Parkin Lot” is an email newsletter that I publish occasionally for like-minded readers, fellow photographers and writers, amateur historians, publishers, and railfans. If you enjoyed this article, you’ll enjoy The Parkin Lot.

I’d love to have you on board – click below to sign up!