History as a Watercourse Westward By Rapid

It’s no revelation that water presents major challenges to rail construction. Yet it’s interesting how, even as CPR builders expended millions of dollars and untold effort avoiding lakes, muskeg, rivers and even small watercourses; they sought remote headwaters to pass over mountain ranges, named water bodies after their experiences, and always acquiesced to the power of water.

This article is about some of those western pathfinders, surveyors, workers, and travellers in their own words. You may know many by name already.

They strove to tell their stories as maps, prose, poetry, art, and photography. The spelling, expression, and punctuation of the original authors is as they wrote it. The only exceptions are my clarifying insertions within square brackets. Most stories date from before or during railway construction. This period of exploration, surveying, and early tourism isn’t often covered by contemporary media, which tend to focus post-1900. As with my opening poem, we’ll follow the flow from pass to Pacific.

All these rivers of Canada, flowing to the sea,

such names they call aloud; ‘Come join our foamy spree!’

Winding down their west-worn slopes, finding the way to go,

each one on a different course, down to salt below.

Starting up Rivers Bow, then Bath, knowing Rockies high,

Let us gain a railway route across this Great Divide.

Down the frothing Kicking Horse, plunging o’er Wapta Falls,

who’s to say which route is right; the one past all these walls?

Next I cross the Columbia—flowing its odd way,

first to north, then to south; yet never to English Bay.

Each branch and every Bend I find, seems to say to me,

‘Come this way, you’ll see—this way to the Monashee.’

Up the Beaver from its mouth, then up again the Bear,

wildlife knew of all these routes, ages before my stare.

High among the alpine firs, higher than Lyall’s larch,

bridge timbers they once did form, over some wat’ry arch.

Mountain summits, Selkirk snows, streams so glacial cold,

Rogers found them before the rest; Major was so bold.

Lower here, yet again, the river Liberty,

torch held high—Columbia—lamp of history.

Next to Eagle Pass, where within a maul did strike,

bolting iron rail with yet more fishplate; Last Spike!

Simon Fraser, Thompson, lake of Kamloops Fort,

red-backed salmon swim over nuggets d’or,

Boiling rapids, Jaws of Death,

baptismal bubbles of last breath.

Each and every course so wide

now flows to the Salish tide,

Beckoning to you and me,

‘Come down with us to the sea.’

© 2022 TW Parkin

However, we begin in present-day Alberta, where some waters flow to Hudson Bay. Once the proposed Yellowhead Pass route over the Rockies was abandoned by the CPR, the Bow valley provided surveyors with a reasonable alternative up from the prairies, well into the encroaching summits.

Much has been written about this length of track, but two incidents bring forward characters, the origin of names, and a sense of the dangers encountered by those finding a way into British Columbia.

Bow River

A short distance above the Kananaskis we crossed the Bow River to the north side. One day, while continuing the line towards the gap, we saw a raft with three men on it come sailing down the river in the swift current. We ran to the edge of the water and waved and shouted to them to come ashore as there were falls ahead. They must have heard us, but seemed to think we were joking, as they only laughed and waved their hats. We ran along the bank but the current was so strong that they soon passed us. We followed down-stream to some distance below the falls, but found no trace of them, or of their raft, which was no doubt torn to pieces in the falls. We never learned who they were or where they came from.

“They sailed upon her waterways and they walked the forests tall.” With youthful folly, the author (left) once attempted to raft the Bow River from Lake Louise to Banff, AB. After striking a log jam and nearly drowning, he now strongly discourages such recreation.

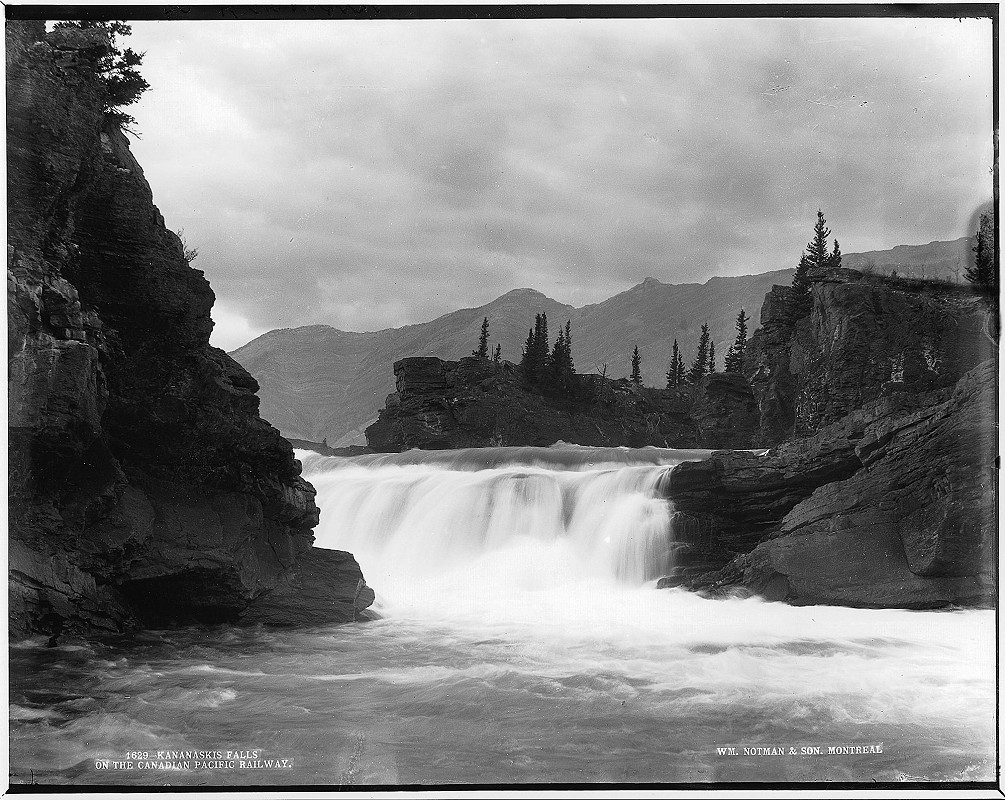

These are Kananaskis Falls that claimed three lives in 1882. They once flowed beside the CPR, but today have been flooded by the Ghost Dam reservoir. Photo by William Notman in 1887, McCord Stewart Museum, VIEW-1629.

Bath Creek

Wilson and “Hells Bells” Rogers . . . the Major’s popular name in both St. Paul, Minnesota, and here, galloped back towards the Bow. It was a very hot day and when they reached the large creek, flood waters halted them.

All glacier-fed streams rise in the afternoon and subside in early morning, what had been a smooth flowing, easily-forded creek earlier in the day was now a raging torrent. Wilson advised waiting until morning; the advice was greeted with a string of vitriolic oaths.

“Afraid of it, are you? Want the old man to show you how to ford it, do you?” And with that shot, Hells Bells spurred his horse into the stream.

It all happened in half a minute . . . the current swept the horse’s legs from under it, rider and horse parted company. Rogers disappeared in the foaming, silt-laden water. Wilson picked up a long pole and pushed it out to the major as the latter bobbed to the surface. The rescue was effected and the horse struggled ashore some distance downstream.

After that, whenever the creek ran high and silty, the pathfinders would grin and holler “Yippee! Yippee! The old major’s taking another bath.”

Laughter at Rogers’ expense 140 years ago is still commemorated today by this placename. Bath Creek still fluctuates diurnally, particularly in summer. Here it shows the characteristic milky colour indicating the water originates from a melting glacier. Photo © TW Parkin.

“When the green dark forest too silent to be real.” Here the CPKC mainline parallels Bath Creek for much of its lower course. This location is in Banff National Park, AB, and its waters run to Hudson Bay. Photo © TW Parkin.

Kicking Horse River

This river tale was told long after it happened, but in authentic voice by respected mountain chronicler, Mrs. Mary Schäffer. She was at first a summer visitor from the US, but remained after marrying a contemporary of Tom Wilson who himself was a mountain guide. The story unfolded in the CPR hotel Glacier House near the summit of the Selkirk Mountains.

I was sitting in the tiny office of Glacier House. A rather short, snowy-haired man was talking to a lady behind the desk. Though from across the border . . . when I heard the words “Palliser”, “1857”, “Kicking-horse”, I had the ill manners to listen, then rose and slipping over apologetically asked if I might hear too.

The kindly little lady [undoubtedly the hotel manager, Mrs. Julia Young, who knew of his coming], knowing my greed for all this history of the hills, introduced me to “Sir James Hector”. Here was a piece of good fortune I had not expected, and certainly did not let pass. He was a good talker and most willing to describe in detail the facts which all may obtain in Palliser’s journal—providing they are lucky enough to come across a copy.

Just as I slipped up to the desk he was in the midst of the following conversation. Bringing his fist down hard on the desk, he said—

“Yes, it is my first visit into the Rocky mountains since 1861; I mean to go on to Golden and from there up the Kicking-horse river, and then to my grave! I know I can find it.”

“Your grave!” said the little lady in astonishment.

“‘Yes, my grave! Oh, I suppose you don’t know how that river received its name. Well, it was after we had won the good-will of the Indians of the foothills. They were very ugly at first, refused to let us go into the mountains at all, claiming that we only wanted to go there for game. I thought the expedition had about come to an end. Then dysentery attacked their camp. I went over to see what I could do for them. I gave them some medicine, changed their camp-site, the disease died out and after that they were willing to do anything I asked of them. They gave us guides to lead us over their trails and with a picked bunch of men we set forth to explore the mountains. We crossed what is now known as Vermilion Pass to the Kootenay river at its head, then down the Beaverfoot river to a river which joints it at the present station of Leanchoil, then followed the unnamed river to the eastward trusting it would bring us back to the permanent camp in the foot-hills. I think from the maps that the rail-road has issued, that the town of Field must be very near my grave. We were having our own troubles getting up this unnamed river, crossing and re-crossing wherever we could find any sort of footing for the horses. My own saddle-pony had anything but a pleasant disposition and he hated fording rivers, especially the kind this one was. I was having a good deal of trouble with him at one point, and finally went behind him with a stick. I saw his heels fly up and then knew nothing more for hours. When I regained consciousness, my grave was dug and they were preparing to put me in it. So that’s how the Kicking-horse got its name, and that’s how I come to have a grave in this part of the world.”

He was a most delightful old gentleman. No wonder that it was through his tact the stubborn Indians were conquered and Captain Palliser able to make some sort of report to the home government, even if that report did say there could never be a continuous route from the east to the west without passing through United States territory, “owing to insurmountable obstructions on Canadian soil.”

Near Field, BC the Kicking Horse River (on opposite bank) enters the larger Yoho River. The Yoho has the higher volume, so technically should carry its own name for the rest of its route to Golden, BC. Nevertheless, the Kicking Horse name is appropriate to the nature of its turbulence, which may explain its dominance. Photo © TW Parkin.

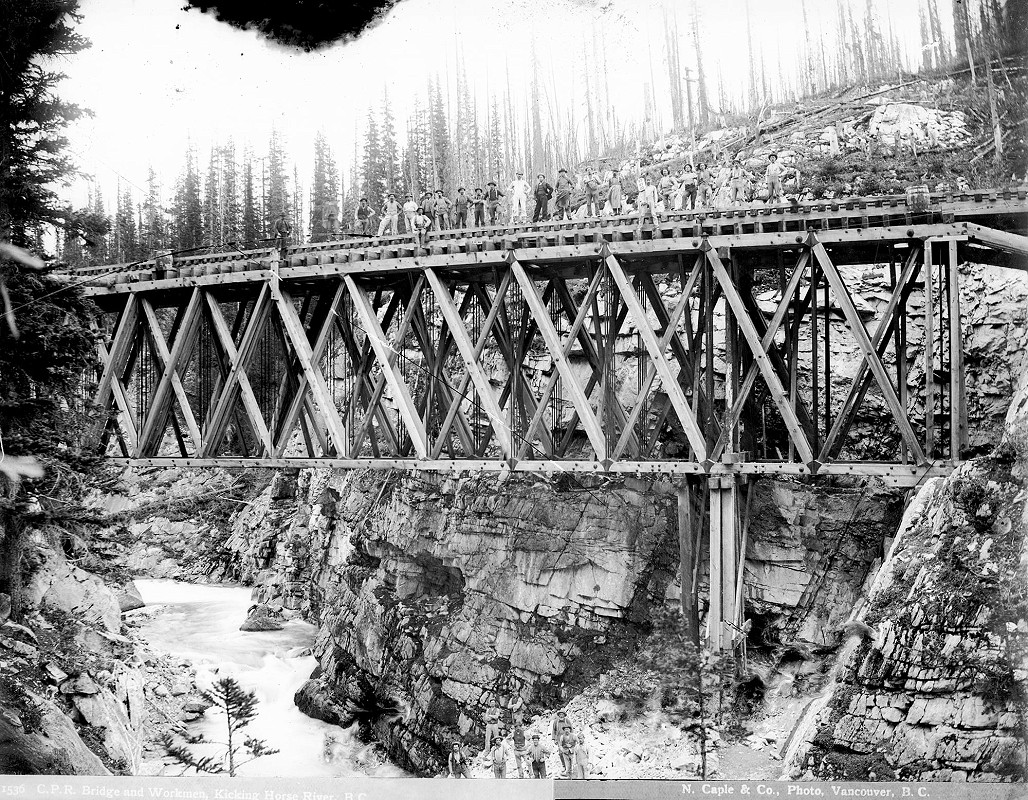

This B&B gang of 22 stand at a truss over upper Kicking Horse Canyon. One holds a mileboard which reads 855. In the canyon bottom are another nine workmen. This is the CPR’s 2nd crossing of the Kicking Horse, counting downstream. A successor bridge stands here today, although abandoned. Photo by N Caple, Vancouver Public Library #14319, circa 1884.

Wapta Falls occupy the full width of the Kicking Horse River, and drops 30 m (98 feet). The ford just above this cataract is where James Hector had his equine misadventure. The rocky ridge behind rises 7400 feet (2200 m) higher than the falls. Photo © TW Parkin.

Columbia River

Today the Town of Golden occupies the confluence of the Kicking Horse and Columbia Rivers. There was a lot of survey activity in this general region during the years the CPR was trying to weave through the mountains. AB Rogers and fellow surveyor CA Shaw had previously worked in the same Calgary office, where Shaw’s revision of Rogers’ badly located lines saved the CPR an estimated $1.35 million in construction costs, just between Cochrane and Banff! It was severely embarrassing to the bellicose bully. Rogers continually used foul language and aggressive behaviour as a way of dominating both underlings and peers.

We passed down the Kicking Horse Valley and finally reached the supply depot in the Columbia valley. Major Rogers came out to meet us—a tall, thin man with Dundreary whiskers. He had a large patch of buffalo hide with the hair still on it, sewed to the seat of his pants. He had evidently forgotten me, for his greeting was, “Who the hell are you and where the hell do you think you’re going?”

I answered sharply, “It’s none of your damned business, to either question. Who the hell are you, anyway?”

He answered, “I am Major Rogers.”

I then said, “My name is Shaw. I’ve been sent by Van Horne to examine and report on the pass through the Selkirks.”

This made him fairly froth at the mouth. He said, “You’re the —— prairie gopher that has come into the mountains and ruined my reputation as an engineer,” coupled with considerably more profanity.

I was now getting annoyed, so I jumped off my horse and seizing him by the throat, shook him till his teeth rattled. I said “Another word out of you, and I’ll throw you in the river and drown you.”

The source and course of the Columbia River and its major tributaries were well known by 1883. In fact, the river had been given its ‘American’ name by Captain Robert Gray of the sailing ship Columbia in 1792. At that time, no European had the foggiest notion of its length or origin. Nevertheless, over time, the river lent its name to the entire watershed, the British colony in its upper reaches, and later, Canada’s westernmost province.

Explorer Christoforo Columbo has been erroneously credited with discovering the New World, and over time, a derivation of his name came to personify the entire USA. You will recognize Columbia as the ‘lady of the lamp’ at the beginning of Columbia Pictures films, and associatively, the Statue of Liberty. She is a demi-goddess representing freedom, progress, and independence1.

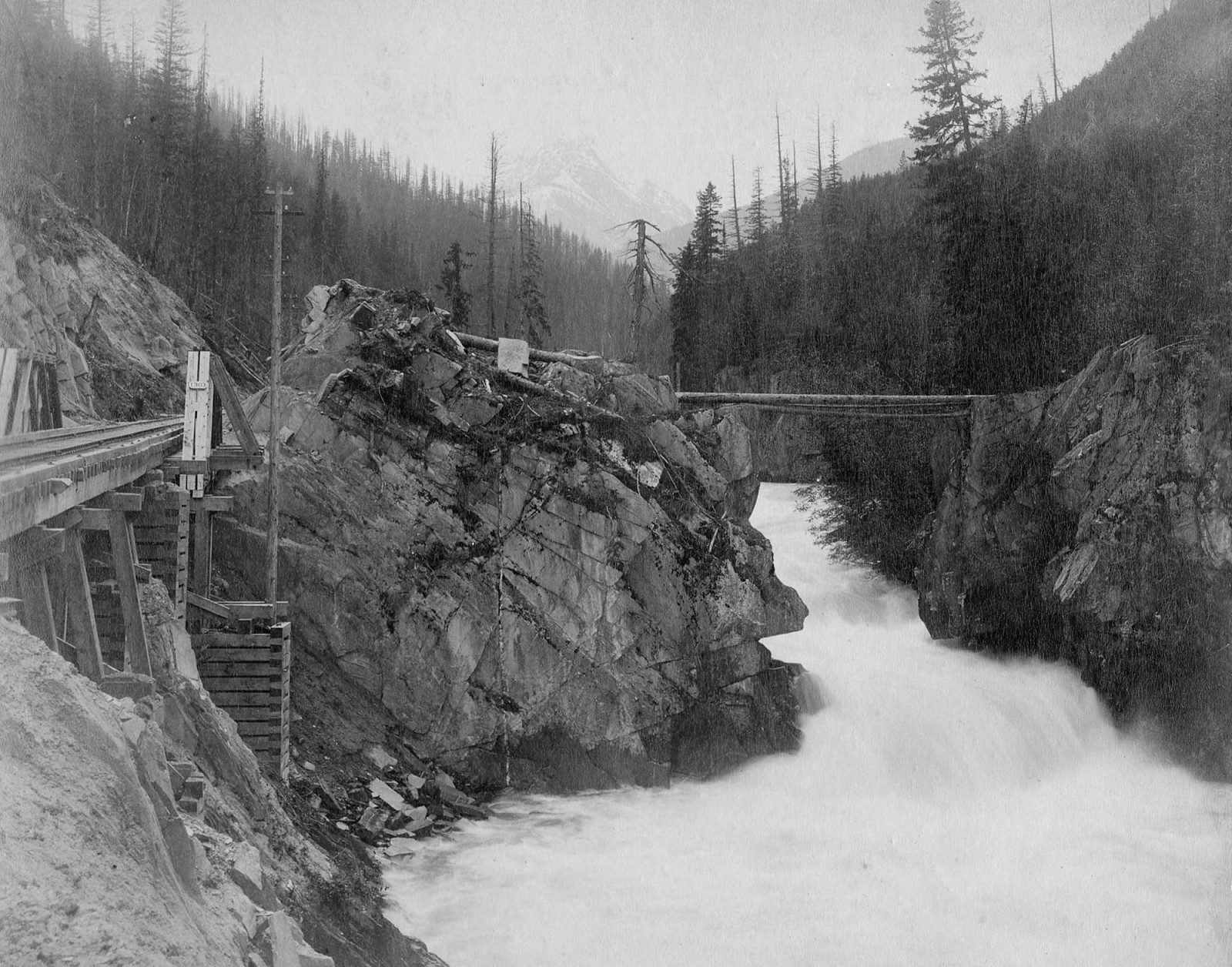

The lowering snow and incomplete nature of this structure suggests the era is the fall of 1885, about when the CPR drove its last spike at nearby Craigellachie. The new town of Farwell (later Revelstoke) can be seen through the mist on the opposite (east) bank of the Columbia River. Photo by Alex Ross of Calgary, possibly during the same trip as his last spike photographs. CRHA/Exporail/Canadian Pacific Railway Company Fonds A.20646.

Beaver River

Close to the railway bridge over the Beaver, there was another bridge of an entirely different type. It was a pack-trail bridge consisting simply of three logs pinned together, and spanning a narrow gorge of the river. Over it the pack-horses of the locating engineers had crossed back and forth when the line was being located. Although no longer in use, this unique relic was then still existing...

This river was named by locating engineers, possibly one Jack E Griffith, after whom a local siding was later named. Griffith became Chief Engineer of the Mountain Section and later, Deputy Minister of Railways in BC. Near the point where the Beaver once discharged into the Columbia River, a pusher station was built. It was, naturally, called Beavermouth, but no longer exists due to the raising of Kinbasket Lake reservoir.

Early photographers often took a variation of this scene. The view is up the Beaver River through a fanged gap once known as ‘Devil’s Gap’ until the more impressive Hells Gate on the Fraser River came to dominate. The span from bedrock to bedrock was an ideal place to drop across logs for early packhorse trains. Photo by Charles Macmunn, circa mid-1880s.

Loop Brook

Loop Brook and its larger companion, the Illecillewaet River, are not specifically mentioned in my poem, but, as implied, both are glacier-fed. I challenge you to think of a word which rhymes with Illecillewaet! The name was first recorded by railway route finder Walter Moberly, discoverer of Eagle Pass in 1865.

The timber meanders built here twenty years later crossed both the brook and the river. Turner Bone writes of working on them as well. They formed a series of trestles used to wind the track up the western slope of the Selkirk Range. Glacier House lay just east of them, just below Rogers Pass summit. Rogers Pass was the ‘shortcut’ across the Big Bend of the Columbia between Donald and Revelstoke. The pass itself is formed by the headwaters of the Rivers Beaver (eastern slope) and Illecillewaet (western).

After leaving Glacier House, we entered at once on the scene of the engineering feat which is celebrated from end to end of the C.P.R., and throughout Canada.

The line descends 600 feet, and so gets down the pass, by a series of double loops, some six miles long in all, accomplishing, however, barely two miles of actual distance.

There are four, or more, parallel lines of railway, running closely to each other generally, but each at a different level. The line is carried largely upon trestle work, crossing and recrossing the river which runs down the cañon, and finally resumes its proper course along the Illecillewaet [an Indigenous term meaning "swift current”].

It is a very deep and tortuous valley that this rapid torrent of green glacier-water thunders through. Tunnels and snow-sheds along its course are numerous, and trestle bridges very frequent. I think we must have crossed this stream from bank to bank a dozen times at least, and often on a timber bridge 150 feet above it.

Looking back to the heights from whence we had come, the cluster of mountains of which Mount Sir Donald is the chief, showed us a magnificent sight. Clouds were hanging about their bases, and their peaks were sharply defined against the deep blue sky.

We were in a sleeping car again now, and there were more passengers, a doctor with his wife and sister among them. These new acquaintances were not as full of excitement and delight as we were at what we were passing through. They had been snowed up at the Bow for two days, until the same bridge we walked over was repaired, and they were stopped for two days more at Field, whilst some burnt bridges over Beaver River were made safe to cross. Their experience had been, so far, very much like ours; but they seemed to think nothing of it, and to care less.

English painter and amateur naturalist Edward Roper last travelled across Canada in 1890, and published his observations and art in By Track and Trail Through Canada the following year. That was also the year he died, aged 37. His book has been reprinted in various forms since, and provides interesting commentary on Canada (and the CPR) during the Victorian era.

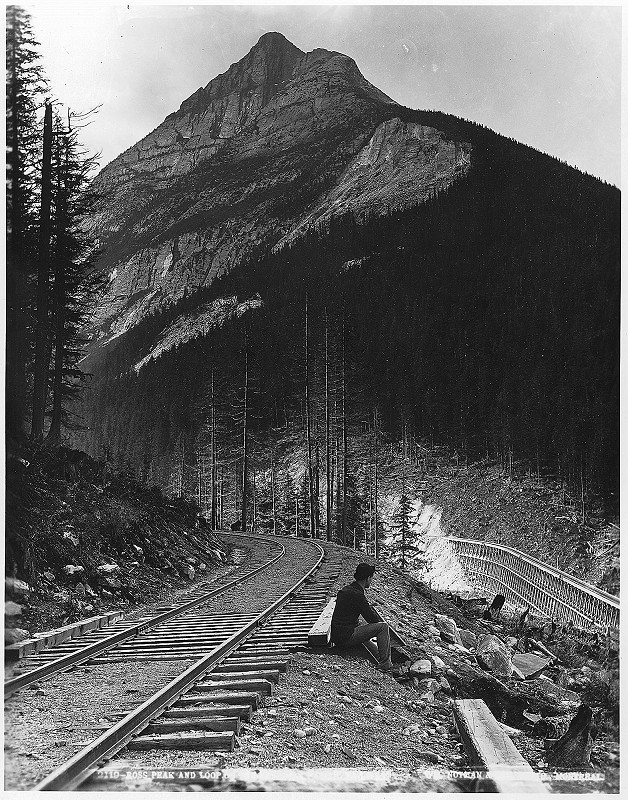

Ross Peak and the upper part of "the Loops" on the CPR mainline below Glacier House. By simply shortcutting down this embankment, a walker headed to Cambie siding below could save one mile over the track route. Photo by Wm. McFarlane Notman, 1889. McCord Stewart Museum, VIEW-2119.

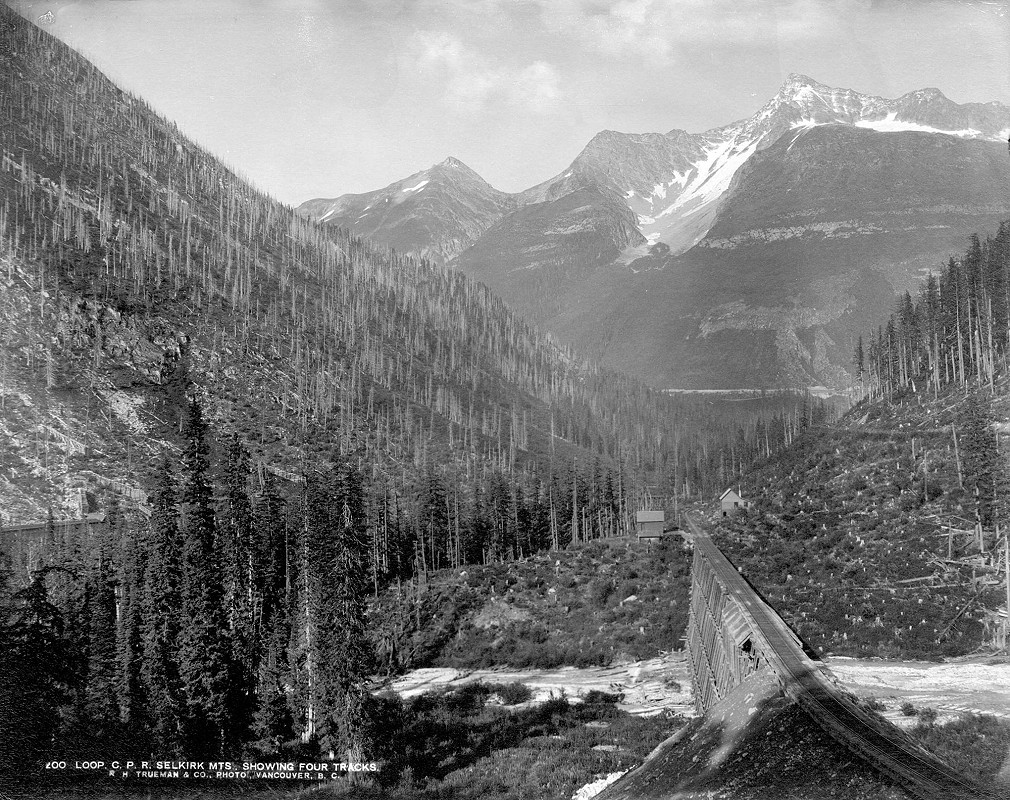

Four segments of winding track show here, looking east over Loop Brook trestle. The highest segment ascends left to Rogers Pass summit (out of sight). The building on the far side is new, and came just in advance of two sidetracks which were installed when masonry and concrete gangs came to build piers and abutments for steel bridge replacements. Photo estimated to be 1899, by RH Trueman.

This 60-foot arch near the siding called Illecillewaet was built of Fraser Canyon granite in 1900. Now at Mile 99.5 of Mountain Subdivision, it was abandoned in 1938 in favour of a 2.8-mile track realignment between Downie and Illecillewaet which avoided problematic avalanche slopes. Photo © TW Parkin.

Eagle River

Eagle River drains the Monashee Range, flowing west into Shuswap Lake. The railway enters the Monashees immediately after crossing the Columbia River at Revelstoke, subject of an earlier article by this author (Canadian Rail, May—June 2021, pp. 158-169).

Rogers and Wilson, introduced at the beginning of this article, were both present at the driving of CP’s last spike beside the Eagle River on 7 November 1885. Engineers and others from the west joined them. Haney and Cambie are such names still recognized in British Columbia.

Sicamous has become the standardized spelling of the local village, which in Secwepemc language means “narrow” or “squeezed in the middle.” Shuswap itself is an anglicised pronunciation of these peoples. They once caught salmon here each fall, when the near shores concentrated the passing fish.

Railway construction imposed great change here, as documented by a visiting reporter. He recognized that yet another transition would soon be in effect. Today, Sicamous styles itself as “Canada’s Houseboat Capital,” rival to the Trent-Severn National Historic Site in Ontario.

THE ONWARD SWEEP OF THE C.P. RAILWAY

J. Haney, general superintendent of Onderdonk contract [CPR construction from Savona to Craigellachie], Major Rogers and Mr. Cambie, CE, leave Eagle Pass [at that time a steamboat landing near Sicamous] tomorrow morning to meet Van Horne and party at end of track, who will at once go to western terminus. Owing to an accident the rails will not be connected until Saturday or Monday. Eagle Pass is fast becoming deserted.

WESTERN END OF TRACK

The 8 x 10 stores were deserted, with an empty cigar-box or a pack of cards in sight to show its former use, while empty bottles were scattered at every turn. The stud-horse and draw poker tables in the salons were deserted, with the exception, perhaps, of the latter, a small number remaining indulging in a game to pass the evening away.

We were informed that during the progress of the railway sub-contracts business was brisk in the stores, hotels and saloons. Money was flush and was scattered with a free hand, and everybody made money—except the scatterers. All is quiet now, and in another week there will not be two dozen inhabitants in the place.

Eagle Pass is a railway town of the past. Its growth was rapid; its decline much swifter. It is situated at the extreme head of Shuswap Lake, north of the Eagle River and Shikamoose narrows. The view from the town is a picturesque one, the calm waters of the lake being shut in by high hills, their summits at the present time crested with snow.

. . . The town is about two miles from the telegraph station of the C.P.R., which latter is reached by row boat.

Kamploops Lake

This place name too, is a variant of Secwepemc language meaning “meeting of the waters,” describing the confluence of the North and South Thompson Rivers here. A fur trading post was established in 1812 and a community began to develop during the Cariboo Gold Rush of the 1860s. It was still around to supply CPR construction camps starting in 1883.

The south side of nearby Kamloops Lake was proposed as a route for the CPR, but recognized as a problem as early as 1872 by Engineer-in-chief Sandford Fleming2. This rough section is known as Cherry Creek. Major Rogers attempted to locate a route over the problematic bluffs, but in the end, a decision was made to follow the shoreline, which required tunnelling. Despite the vast amount of rock and water here, a fire broke out in 1899:

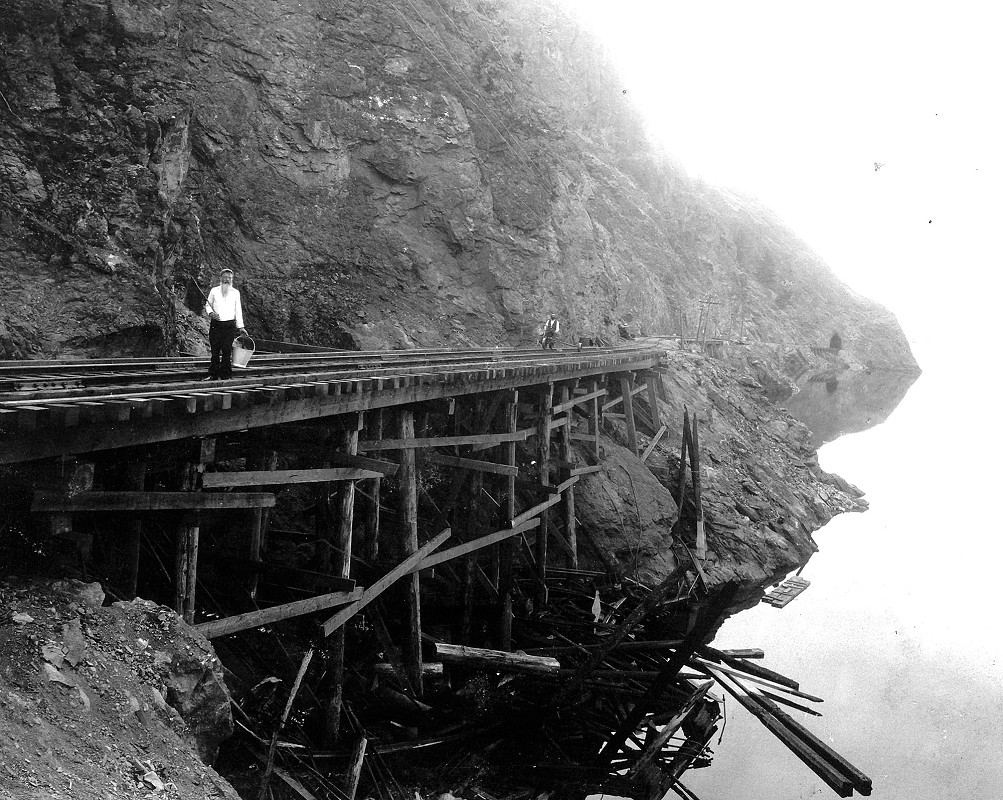

About 7 o’clock Saturday evening, Watchman “Honey” [J Murphy] discovered the C.P.R. Bridge at Cherry Bluff, on Kamloops Lake, 16 ½ miles west of Kamloops, to be on fire. He was then on the east side of the bridge, a Howe truss structure over 160 feet in length. Honey swam around the fire then clambered up onto the track and ran down the line to the section house. Here he was able to telephone particulars of the accident to Savonas. With characteristic dispatch, wrecking and bridge gangs were soon on the spot and work was under way to provide temporary foot crossing for passengers and to prepare for the erection of a new bridge to replace what the fire by this time had completely destroyed. Saturday’s and Sunday’s trains were delayed a few hours, as passengers and baggage had to be transferred from side to side by the gap caused by the destruction of the bridge. It looked at first as though it would be impossible to make any kind of a footpath around the bluff, and it was freely stated that at least a week would elapse before a new bridge could be put in. However, Hugh McDonald’s bridge gang in very short order found a way to erect a plank walk around the steep rocks, and then, with the assistance of other gangs from east and west they set to work on the new bridge. In less than 48 hours the job was completed successfully and the rails re-laid. Over 160 feet of very difficult bridge work, around a steep, rocky bluff and above deep water, is a feat only C.P.R. bridge carpenters could perform in so short a time. By 6 o’clock last evening, the line was reported clear from traffic. Supt. Duchesnay was on hand superintending the work of reconstruction. The cause of the fire is unknown. It is supposed, however, to have started from a spark from an engine. The fact that the fire began at the top of the bridge leads to this theory.

. . . That an appalling disaster was averted was due to the courage, endurance, and presence of mind of William Honey, the bridge-tender, who although 72 years of age, stripped his clothing, jumped into the ice cold water, swam 500 feet to a rock embankment, climbed up its slippery side in the darkness, and naked as he was, ran to a telephone station to send a danger message. The old gentleman may not be of distinguished ancestry, and is probable that he is without a family crest or coat of arms, but he is one of Nature’s noblemen, nevertheless, and we lift our hat in silent acknowledgement of his heroic deed.

Notes with this 3 August 1899 photo by CPR photographer JW Heckman say: “Watchman Murphy [shown in picture] saved Train by swimming 1000 Ft.” Seen in the distance is one of five tunnels drilled through the Cherry Point bluffs on Kamloops Lake. CRHA/Exporail, Canadian Pacific Railway Company Fonds, P170_1377.

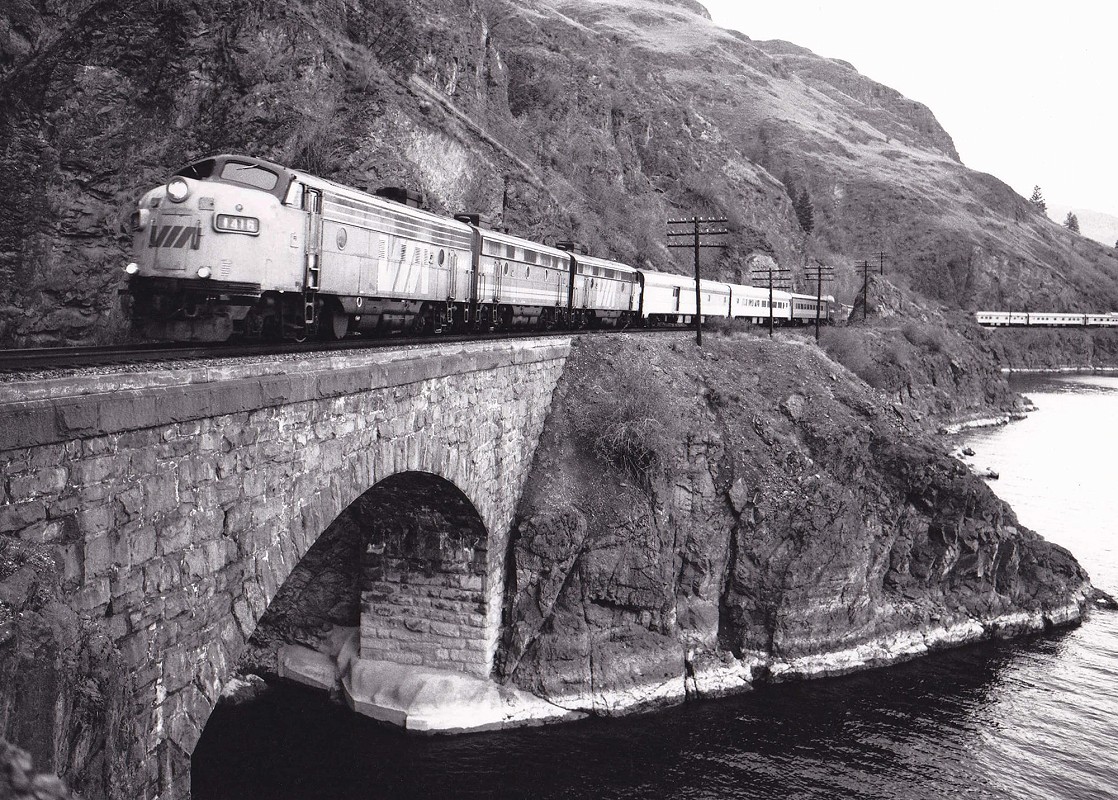

VIA 1416 pulls the Canadian over a granite-arched gap in the shoreline along Cherry Point bluffs, Kamloops Lake. Built in 1884-85, a combination of tunnels and trestles allowed the railway to use a low and level route instead of a higher grade surveyed by Major Rogers. Photographed 11 April 1983 © DJ Meridew.

CP 6053, 5624, and a 5900 eastbound through one of five Cherry Point tunnels along Kamloops Lake, 21 April 1992. The railway was initially built here with extensive use of trestling, but locally quarried granite was later used for permanent support, starting 1890. Photographed 21 April 1992 © DJ Meridew.

Jaws of Death

Jaws of Death was a place name applied by railway navvies working up the Thompson River past Lytton. Surveyors and construction men expressing their stark perils in this landscape recognized its fierce aspect. Nearby names include Indictment Hole, Calamity Curve, and Slaughter Pen. Strangely, although these place names live on in memory, the BC Geographical Names Office has not officially recorded any of them. They are strictly CPR parlance.

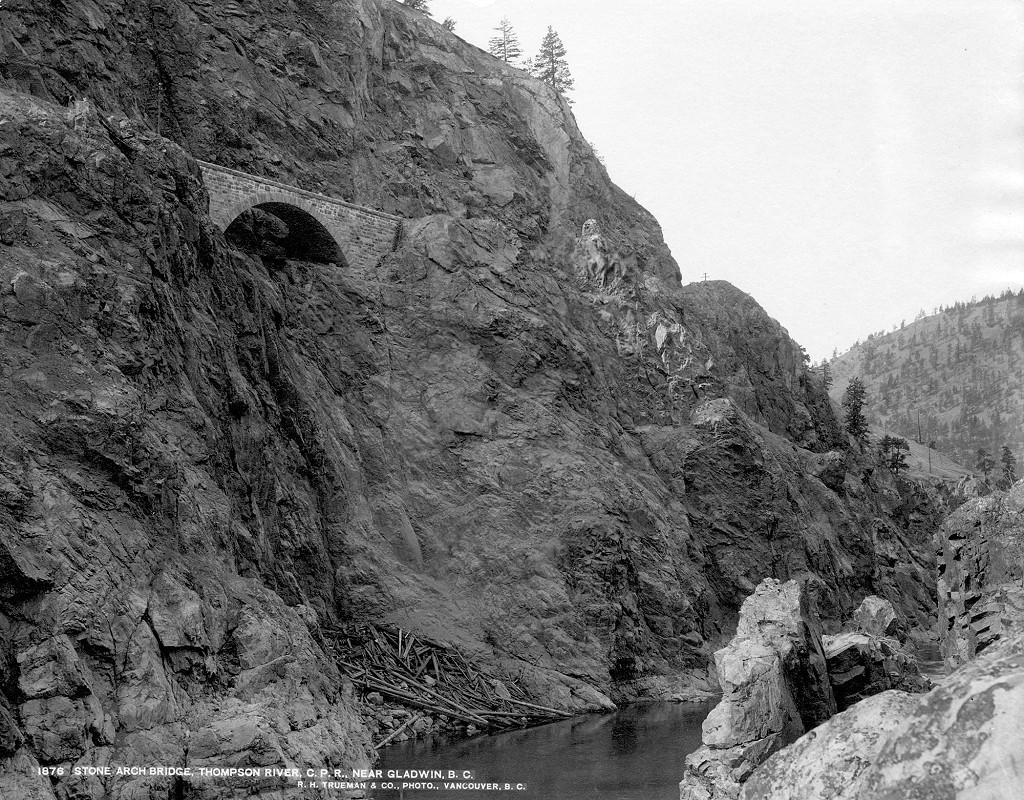

Along the narrow ledge blasted from bedrock above the Thompson River, the roadbed was solid except for a gap—a dry chute down which loose rock cannonaded into the rapids. Typically, engineers dealt with such places by means of ‘grasshopper trestles’ such as described by HJ Cambie below. Jaws of Death was too steep and too exposed for that. A Howe truss set on notched ledges did the job until a stone arch replaced it in 1899.

80-ft stone arch (Jaws of Death), Thompson River near Gladwin, BC. It replaced an original Howe truss in 1898. Photo by RH Trueman, City of Vancouver Archives #CVA 2-39.

Granite arch over a dry gully on CPR Thompson Subdivision at Mile 87.7. This 125-year old masonry continues to carry modern train weights with ease. Many engine crews remain unaware it supports their passage, the work not being visible from a locomotive cab. Photo © TW Parkin.

Fraser Cañon

This Spanish spelling of canyon was once widespread, including by the CPR. I like its historical resonance. Neither of these deaths was recorded by BC’s provincial vital statistics agency; many being missed at that time:

Last week a man named Patrick O’Brien died in great agony at Camp 13 [White’s Creek, Onderdonk Contract 60] believed to be from the effects of drinking ‘Chinese brandy’.

Saturday a railway man named Michael Welch, at Camp 6 went out of his mind from the use of ‘Chinese brandy’ and rushed into the river and was drowned.

We are creditably informed that large quantities of the vile stuff called ‘Chinese brandy’ is being disposed of all along the line. It is about time some active stops were taken to check this poison traffic.

Here at the mouth of the Fraser canyon at Yale, BC, steamboats were obliged to end their upstream journey. A wild west town squeezed between the Coast Mountains and the torrent became headquarters for CPR construction crews blasting inland. Photo © TW Parkin.

Shown here in June 2022, the river is nowhere near as high was when it caused extensive damage to both national railways the previous fall. Nevertheless, the current and rapids would not be survivable for an involuntary swimmer. Back eddies were choked with floating detritus. Photo © TW Parkin.

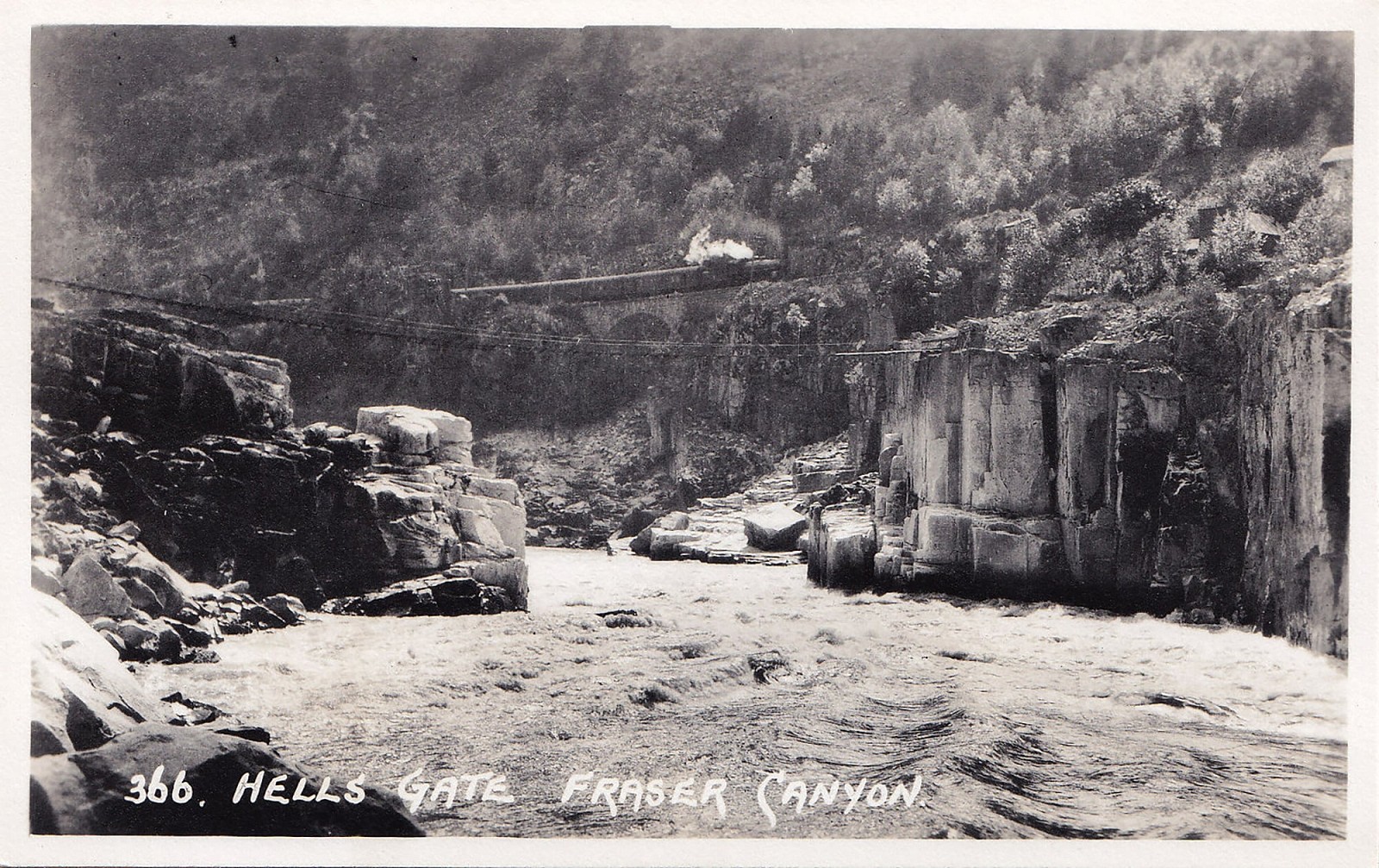

Eastbound CPR passenger train passes over a stone arch above Hells Gate, Fraser River, BC. The pedestrian suspension bridge links the CPKC and CN railways. This is one of the most visually iconic parts of the Fraser. Photo by Byron Harmon, late 1920s.

Salish Sea

Eastern readers of this article may not recognize this inland waterway, formerly known as Strait of Georgia, Strait of Juan de Fuca, and Puget Sound. Collectively, these international waters were re-designated by multiple levels of government in 2010. The name Mer des Salish is also official in Canada3.

The names recognize the precedence of Salishan-speaking tribes, all excellent mariners, who occupied these protected waters prior to arrival of Spanish and British explorers. The Fraser River discharges into the Salish Sea just south of Vancouver and English Bay.

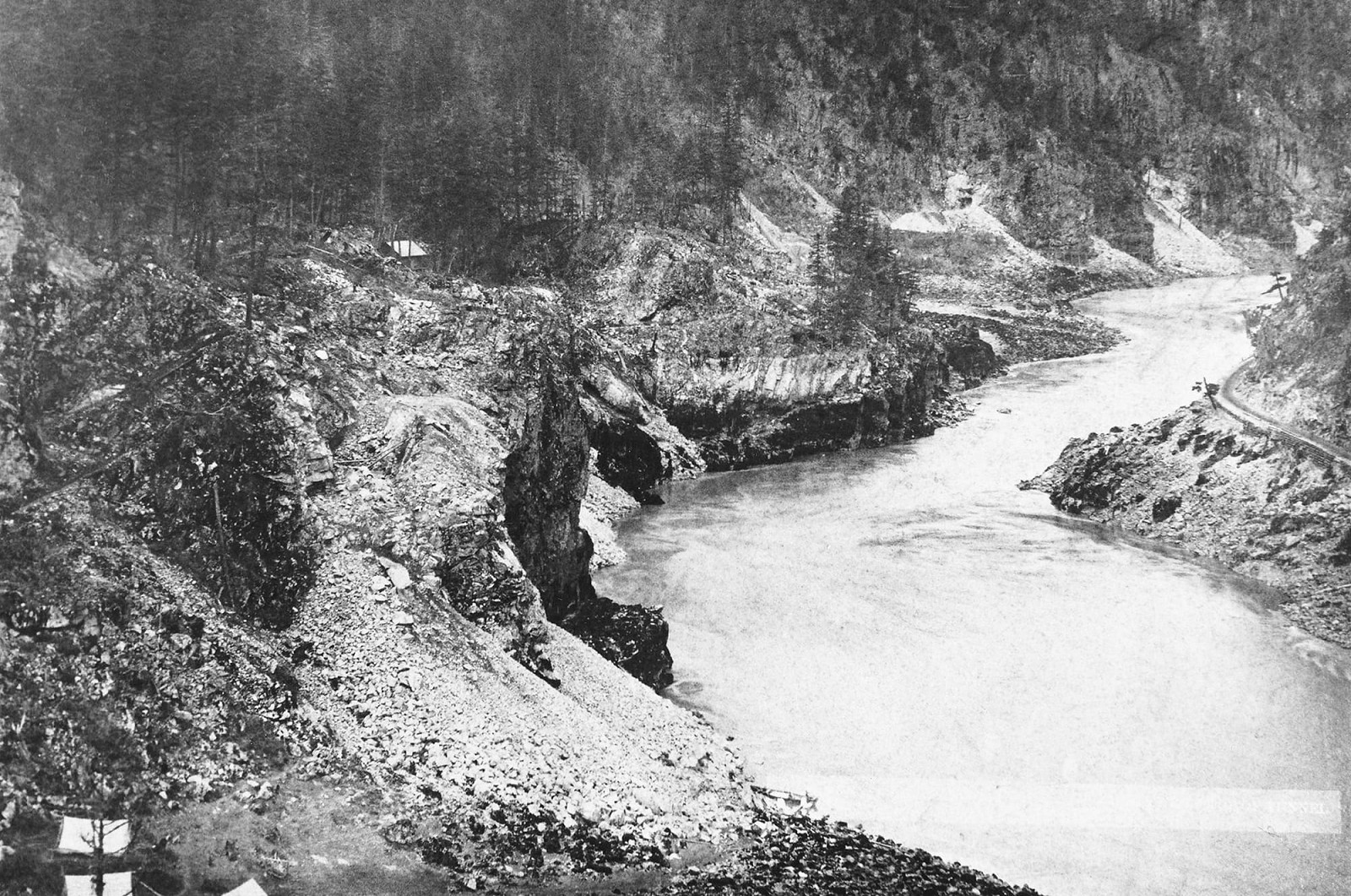

Here at White’s Creek, possibly in 1881, a series of tunnels are being drilled through hard granite of the Fraser Cañon. Two show in the distance, and another has been started in the cliff behind the tents. This was the camp where Patrick O’Brien died of alcohol poisoning. Neither his death nor his grave was recorded. Today these CPKC tunnels lie in Cascade Subdivision. On the opposite bank is the Cariboo Road, a stage and wagon road built for transportation to the gold fields of 1860. Photo by Richard Maynard, City of Vancouver Library # CVL 417.

End of the Line

Our freshwater journey is complete. Rain, snow, and ice all return to the mother of all waters—the sea—and the hydrological cycle begins anew with the next maritime system.

I hope you find rails along any Canadian watercourse, whichever current calls you onward.

References

- https://symbolsage.com/goddess-columbia-american-deity/

- Grant, Rev. George M., Ocean to Ocean: Sandford Fleming’s expedition through Canada in 1872. Originally published 1873, Prospero Canadian Collection edition © 2000, page 297.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Salish_Sea#cite_note-BCGNIS-3

Did You Enjoy This Article?

Sign Up for More!

“The Parkin Lot” is an email newsletter that I publish occasionally for like-minded readers, fellow photographers and writers, amateur historians, publishers, and railfans. If you enjoyed this article, you’ll enjoy The Parkin Lot.

I’d love to have you on board – click below to sign up!