Ghost Town Donald, BC

Legacy Among the Headstones

Forlorn and forgotten, but not forsaken. While many wooden headstones at Donald have succumbed to time and weather, sporadic upkeep suggests that dedicated individuals are determined not to let this legacy vanish into the undergrowth.

The headboards offer glimpses into the lives and times of the people buried here, with their inscriptions, symbols, and carvings reflecting culture, faith, and family connections.

The cemetery at Donald was established in the mid-1880s, alongside the construction of the CPR’s transcontinental line through the valley. Donald flourished briefly, its future once looking bright, only to fade away almost as quickly as it rose. This burial ground is a poignant reminder of how transient life and prosperity can be. Photo © TW Parkin.

A Personal Connection

I’ll never forget the moment I discovered my great-grandparents’ names for the first time, engraved on a granite spire in Ontario. It was a discovery no one in my family had made, revealing where our ancestors came from and where they now rest. I even have a photo of myself embracing their gravestone, overcome by a profound sense of connection to people I’d previously known only through genealogical research.

Though Sir Smith isn’t buried here, I feel a personal connection to this remarkable man.

My passion for railway history has similarly drawn me to Donald, a former Canadian Pacific Railway (now CPKC) divisional point. Donald was named for Sir Donald Smith, the Scottish financier who famously drove the Last Spike at Craigellachie, BC. Smith was instrumental in the CPR’s early success, and Mount Sir Donald, towering over nearby Glacier National Park, also bears his name.

Though Sir Smith isn’t buried here, I feel a personal connection to this remarkable man—he once owned Colonsay, the Hebridean island from which my ancestors left for Canada in 1859.

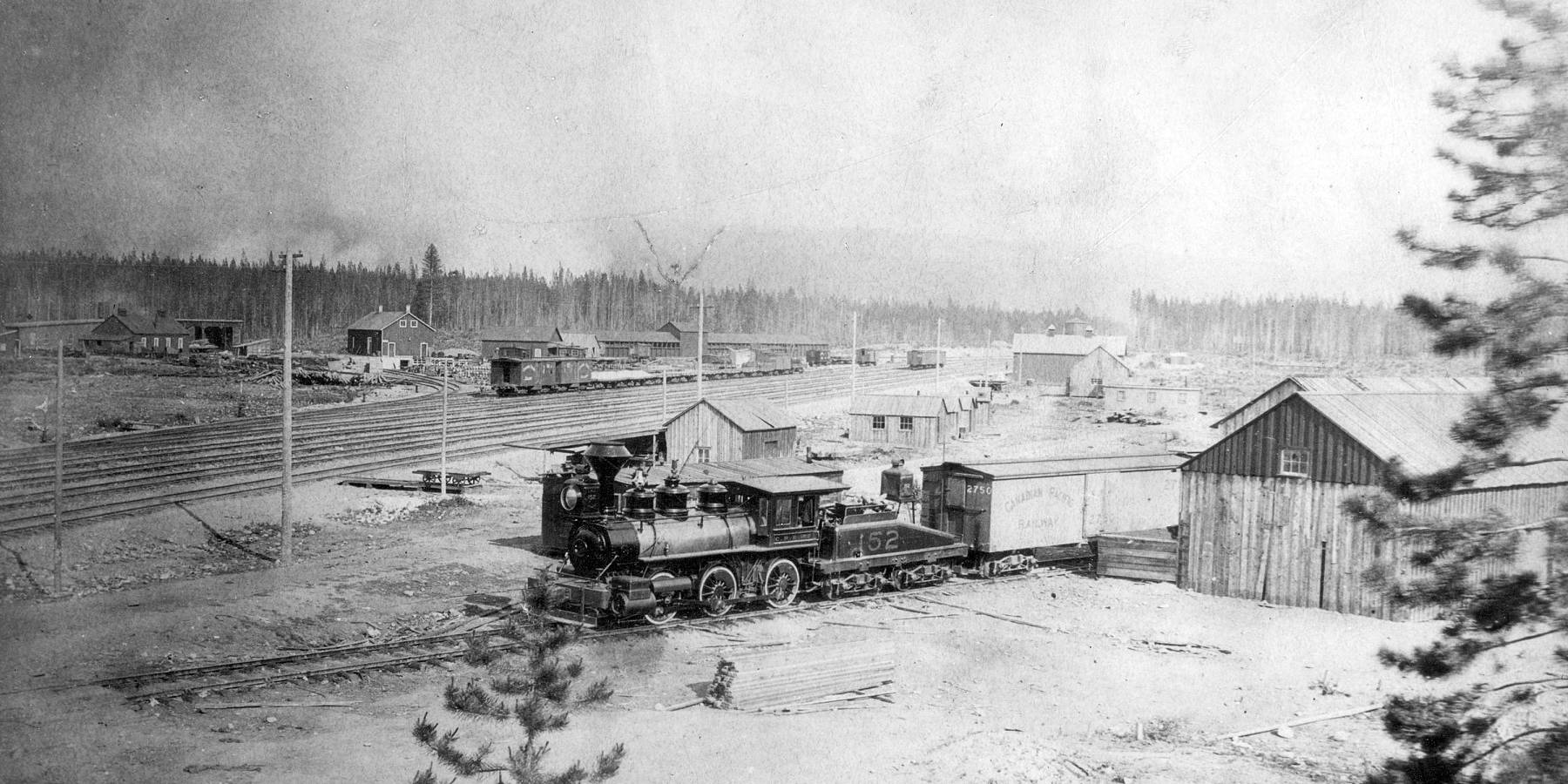

Mount Sir Donald on the right skyline. The post in the foreground suspends a “tell-tale,” a safety device of ropes hanging from its horizontal bar. These ropes would brush against a brakeman walking on the roof of a moving train, warning him to duck to avoid being struck by an upcoming obstruction—such as the snowshed seen here. Postcard circa 1910.

The Heyday & Decline of Donald

After the railway’s completion in 1885, CPR crews running east from Revelstoke would stop at Donald before picking up another train for the return west. Today, those same crews continue past Donald to Field, deep in the Rockies.

In its heyday, Donald was home to 500 residents.

This shift underscores the challenges of railway operations in the late 19th century. Back then, crews could manage only 79 miles (127 kilometres) in a day, labouring over steep grades, precarious track conditions, and with regular stops to refuel their steam engines with wood or coal, plus water.

In its heyday, Donald was home to 500 residents. While many lived in CPR housing, the town also supported mining and lumbering. Substantial buildings, including a station, locomotive roundhouse, school, courthouse, three churches, four hotels, and significant residences, made up this lively community.

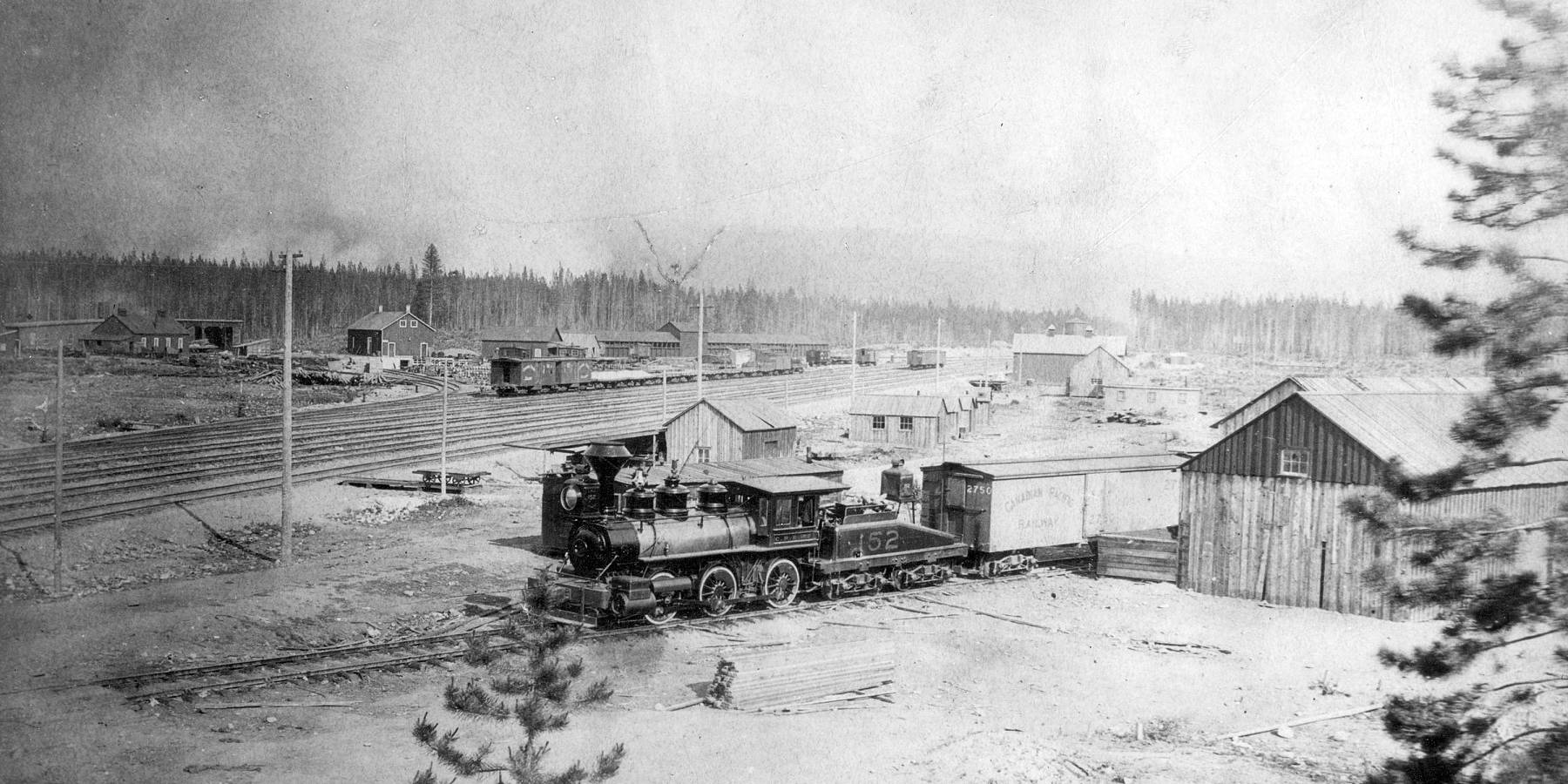

This standard road engine ran between Canmore, AB, and Donald, BC, where it appears here on the turntable. Note the metal receptacle into which the tapered timber lying nearby was inserted. This was for turning the table by “the Armstrong method". The “cowcatcher” (properly called a pilot), is also made of wood. Photo by Norman Caple, circa 1891. Vancouver City Archives #LGN 652.

The white building on the left is the Selkirk Hotel, one of Donald’s key establishments during its heyday. To its right stands Forrest House, another hotel serving the bustling railway town. Photo by Bailey Bros, circa 1891. City of Vancouver Archives #Out P54.2.

The cemetery, located on the edge of town along the railway tracks and overlooking the Columbia River, was as serene a spot as one might find in those days, with the forest still encroaching on the settlement. A great-uncle of mine operated a sawmill here at the start of World War II but was defeated by the heavy snow and, ultimately, his untimely death. Today, little remains of his operations—or of the townsite itself.

Years ago, the Golden Historical Society took on the cemetery as a project, clearing trails and installing a large sign detailing the names of those buried here. Even then, trees were reclaiming the site, and today it has nearly returned to nature.

In 1899, the CPR closed its Donald operations and moved everyone.

Among the native flora, one can find lily-of-the-valley—a fragrant white flower with symbolic roots in the Victorian era. Introduced intentionally, it was meant to signal the Second Coming and a symbol of hope for a better world. For the grieving, it provided comfort—a gentle reminder of life’s enduring connection to eternity.

In 1899, the CPR closed its Donald operations and moved everyone, including personal homes, the courthouse, and two churches, wherever people needed them. It was at this time the famous incident of the “stolen church” occurred, but that’s a story for another time.

Most CPR employees ended up in Field and Revelstoke. The town was at its lowest ebb at this time. Let’s now look at a few former inhabitants:

A prospector named Corrigan, of Donald, was found dead in his cabin on Bald Mountain on Tuesday. It seems that he went out some time ago to a claim which he owns on the mountain. The trip seems to have exhausted him, for he had evidently just got inside his shack, shut the door and dropped dead while in the act of taking off his clothes and going to bed. He had been dead a long time. Volunteers were called for at Donald yesterday to bring the body into that town. He was 60 years of age.

Residents of Donald deny in toto that there was any unseemliness about the burial of the old man Corrigan, who was found dead in his shack at Bald Mountain. From the posture into which the body was frozen it was impossible to put it into an ordinary coffin, so one was made for him of the best cedar in town and the funeral service was conducted with all reverence by the Donald school teacher.

Personalities Remembered

Corrigan’s burial is recorded at Donald, but no trace of his grave remains—perhaps he was too poor to afford a marker. After the CPR moved its operations to Revelstoke, some older and displaced men found refuge in the remnants of the town, living frugally and often in isolation.

A railway acquaintance of mine once visited an old squatter in his shack during the mid-1950s. Curious about the contents of a pot boiling on a battered tin stove, he lifted the lid—then quickly slapped it back. Supper was two gophers, fur still on, simmering away!

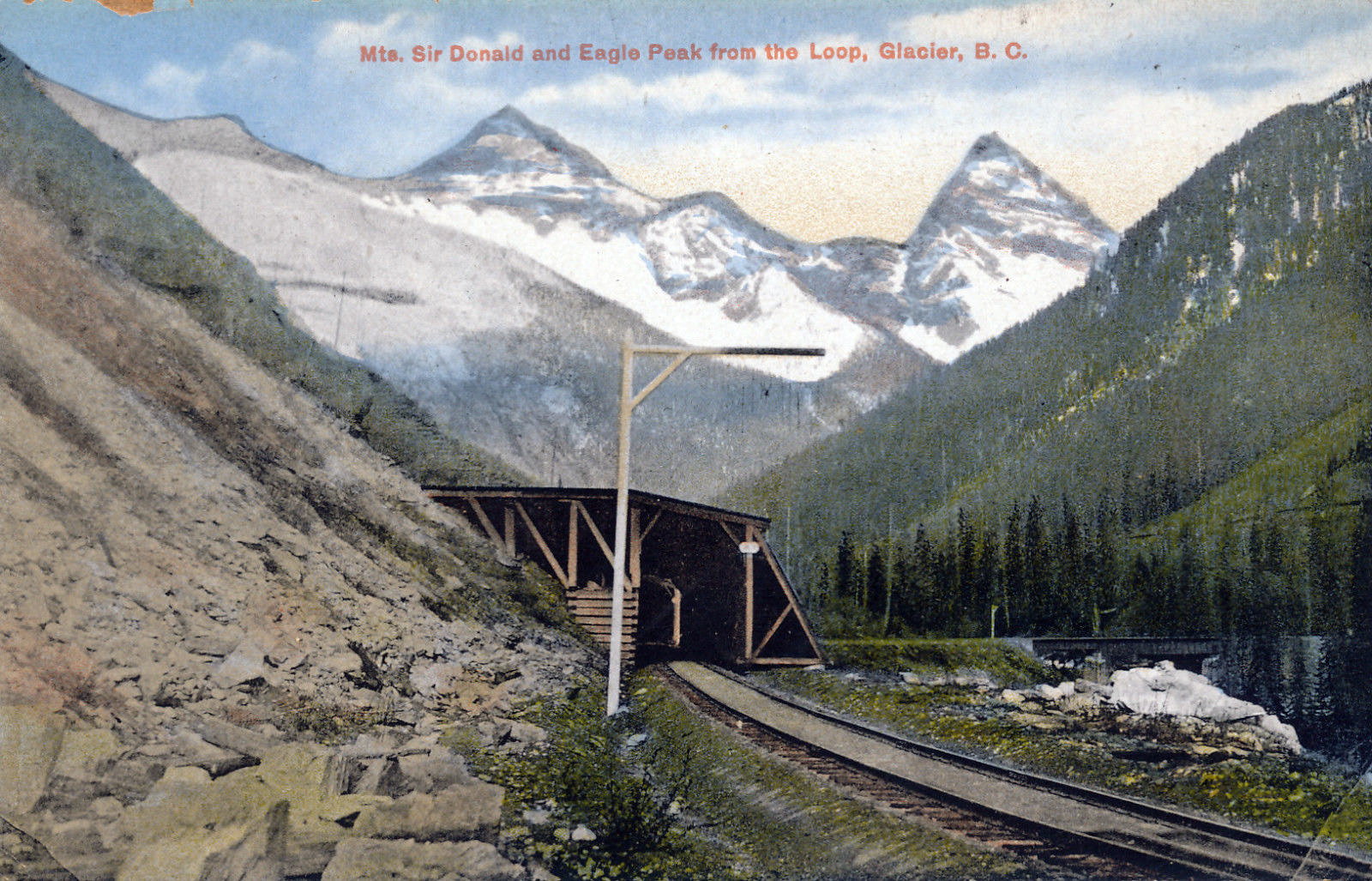

CPR roundhouse and crew at Donald, circa 1887–89. Water barrels can be seen on the roof for fire-fighting purposes. In those wood-burning days, the funnel-shaped stacks on locomotives, such as the one on #376 seen on the turntable, were designed to catch sparks. The tender is piled high with cordwood, ready for the journey. Two dogs are also part of this group, which appears to include nearly everyone in the vicinity. Having one’s photo taken was a rare event, so participants struck deliberate poses. The dapper gentleman with the bowler hat in the foreground is likely Frederick E. Hobbs, the shops foreman. The tall man in the back row to the right wears a blacksmith’s leather apron, identifying his trade. Can you spot other trades represented here? Glenbow Museum photo NA-2216-4.

Not all stories of Donald are so somber. Personalities were larger-than-life in those days, and several CPR men have had their names immortalized—not in the cemetery, but across the landscape. Sheriff Stephen Redgrave ensured order in a bustling railway town—to the extent he put his own son, a constable, in the clink for murder.

CPR superintendent Richard Marpole had a Vancouver neighbourhood named for him, and CPR civil engineer John Griffith must have been well-liked by the local editor:

The boys tell this one on JE Griffith, engineer-in-chief of this division of the Canadian Pacific. A pressing engagement called him east last week. The evening of the second day he ate a hearty supper, partaking liberally of Welsh rarebit, a favourite dish. At the usual hour are retired to his berth in the sleeper, and was dreaming of levels, cross sections, tangents, glance cribs and 4 1/2 percent grades. Just as he struck the latter subject, he imagined the train was climbing the Big Hill, that the train had parted, and the sleeper was taking the back track down the western slope of the Rockies at a rate of a mile a second. He jumped out of his berth, made for the rear platform, and set the brake so tight that it almost stopped the train. While twisting the brake he awoke, only to find the night wind flirting with his shirttail, and the train moving slowly over a dead-level Manitoba prairie.

Visiting Today

Although a sign on Highway #1 (west side of the Columbia River bridge) marks the turnoff to Donald cemetery, it’s not a tourist attraction. Next time you pass by, take an hour to deke into Donald. There you’ll find a poignant reminder of the railway’s impact on western Canada.

Whether educating children about our shared history or simply reflecting on the lives of those who came before, you may leave with a deeper appreciation for the society we enjoy today—and for the people who built it.

In Loving Memory Of

The Infant Son Of

Simon And Lorrie Fraser

Died Dec. 11th, 1895

Suffer Little Children To Come Unto Me

Photo © TW Parkin.

In Loving Memory Of Randall David Lindsay

Born Jan. 22, 1889. Died May 2, 1889

ALSO

Gladys Mary

Born Oct. 7, 1890. Died Feb 15, 1891

Beloved Children Of Dr. & Mrs. W. Bell Campbell

Of Such Is The Kingdom Of Heaven.

Photo © TW Parkin.

Did You Enjoy This Article?

Sign Up for More!

“The Parkin Lot” is an email newsletter that I publish occasionally for like-minded readers, fellow photographers and writers, amateur historians, publishers, and railfans. If you enjoyed this article, you’ll enjoy The Parkin Lot.

I’d love to have you on board – click below to sign up!